the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Inter- and intra-event rainfall partitioning dynamics of two typical xerophytic shrubs in the Loess Plateau of China

Jinxia An

Guangyao Gao

Chuan Yuan

Juan Pinos

Bojie Fu

Rainfall is known as the main water replenishment in dryland ecosystems, and rainfall partitioning by vegetation reshapes the spatial and temporal distribution patterns of rainwater entry into the soil. The dynamics of rainfall partitioning have been extensively studied at the inter-event scale, yet very few studies have explored its finer intra-event dynamics and the relating driving factors for shrubs. Here, we conducted a concurrent in-depth investigation of all rainfall partitioning components at inter- and intra-event scales for two typical xerophytic shrubs (Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila) in the Liudaogou catchment of the Loess Plateau, China. The event throughfall (TF), stemflow (SF), and interception loss (IC), and their temporal variations within the rainfall event, as well as the meteorological factors and vegetation characteristics, were systematically measured during the 2014–2015 rainy seasons. Our results showed that C. korshinskii had significantly higher SF percentage (9.2 %) and lower IC percentage (21.4 %) compared to S. psammophila (3.8 % and 29.5 %, respectively), but their TF percentages were not significantly different (69.4 % vs. 66.7 %). At the intra-event scale, TF and SF of S. psammophila were initiated (0.1 vs. 0.3 h and 0.7 vs. 0.8 h) and peaked (1.8 vs. 2.0 h and 2.1 vs. 2.2 h) more quickly, and TF of S. psammophila lasted longer (5.2 vs. 4.8 h) and delivered more intensely (4.3 vs. 3.8 mm h−1), whereas SF of C. korshinskii lasted longer (4.6 vs. 4.1 h) and delivered more intensely (753.8 vs. 471.2 mm h−1). For both shrubs, rainfall amount was the most significant factor influencing inter-event rainfall partitioning, and rainfall intensity and duration controlled the intra-event TF and SF variables. The C. korshinskii with larger branch angle, more small branches, and smaller canopy area, has an advantage over S. psammophila to produce SF more efficiently. The S. psammophila has lower canopy water storage capacity to generate and peak TF and SF earlier, and it has larger aboveground biomass and total canopy water storage of individual plants to produce higher IC compared to C. korshinskii. These findings contribute to the fine characterization of shrub-dominated ecohydrological processes, and improve the accuracy of water balance estimation in dryland ecosystems.

- Article

(5015 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Rainfall is known as the main replenishment of water resources in arid and semiarid areas, and water resource is the key factor limiting the function of arid ecosystems (Chesson et al., 2004; Cayuela et al., 2018; Magliano et al., 2019a). Before entering into soil, rainfall is redistributed by plant canopies into throughfall (TF, diffuse water input), stemflow (SF, point water input), and interception loss (IC, evaporation). The sum of TF and SF is defined as “net rainfall”. Differences in the distribution of net rainfall caused by plant canopy interception alter the spatial and temporal patterns of rainfall entry into the soil (Martinez-Meza and Whitford, 1996; Li et al., 2009; Van Stan et al., 2020), and further profoundly affect the water-use efficiency of vegetation and ecosystem sustainability (Xu and Li, 2006; Lacombe et al., 2018; Molina et al., 2019). In addition, net rainfall could regulate vegetation physiological–metabolic processes through nutrient enrichment (Levia and Frost, 2003; Zhang et al., 2016; Van Stan et al., 2017; Tonello et al., 2021), ultimately affecting the carbon balance of ecosystems (Chu et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2016). In light of the important role of rainfall partitioning in regulating soil moisture and vegetation patch patterns, investigations of the rainfall partitioning dynamics are imperative for a better understanding of the soil–water–vegetation relationships (Molina et al., 2019; Van Stan et al., 2020; H. Zhang et al., 2021).

Studies on rainfall partitioning have been broadly carried out in different climatic zones and various types of vegetation (Gordon et al., 2020; Rivera and Van Stan, 2020; Y. F. Zhang et al., 2021; Yue et al., 2021). Based on a comprehensive global synthesis, Yue et al. (2021) found that most TF and SF observations were measured in forests (n= 718 and n= 816, respectively), and observations in shrublands were scarce (n= 43 and n= 63, respectively), which was mainly because the shrubs have multiple branches, and the rainfall partitioning of shrubs is difficult to measure compared to forests. Shrubs are the dominant vegetation type in drylands, forming fertile islands by intercepting water and trapping sediments, thus providing important ecosystem goods and services (Levia and Frost, 2003; Llorens and Domingo, 2007; Soulsby et al., 2017). However, the lack of information on the detailed dynamics of rainfall partitioning processes induced by shrubs due to limited studies hinders us from a clear understanding of shrubs' ecohydrological role in shaping and sustaining drylands.

Most of the existing studies on the rainfall partitioning by shrubs are based on the inter-event scale (Garcia-Estringana et al., 2010; Magliano et al., 2019a). Magliano et al. (2019a) synthesized that for 27 shrub species in drylands, the mean event-based SF %, TF %, and IC % were 9.4 %, 63.0 % and 27.6 %, respectively. It has been reported that rainfall partitioning by shrubs is determined by biotic and abiotic factors, such as rainfall characteristics (Levia and Frost, 2003; Magliano et al., 2019b) and canopy-structure characteristics (Martinez-Meza and Whitford, 1996; Garcia-Estringana et al., 2010; Yue et al., 2021). Take the latter for example, vegetation with smooth barks, more branches, and vertical branching had advantages in SF generation (Honda et al., 2015; Magliano et al., 2019a; Whitworth-Hulse et al., 2020b), and a simple vegetation structure and low canopy density are generally corresponding to a relatively high TF rate and low IC rate (Soulsby et al., 2017; Yue et al., 2021). The complexity of shrub structure poses challenges to understanding the causes of rainfall partitioning dynamics under different meteorological conditions, and it is necessary to substantially explore the differences of rainfall partitioning dynamics and the main influencing factors among different shrub species (Levia et al., 2010; Sadeghi et al., 2020).

In addition to the inter-event studies, a few intra-event-scale studies have been reported, which are essential for a better understanding of soil moisture distribution and the hydrological cycle in arid regions (Levia et al., 2010; Levia and Germer, 2015; Cayuela et al., 2018; H. Zhang et al., 2021). For instance, Zhang et al. (2018) investigated the TF spatiotemporal pattern of Caragana korshinskii in arid areas of northern China at high temporal resolution (10 min intervals), and they found that temporal heterogeneity of rainfall clearly affected the spatiotemporal dynamics of TF beneath shrub canopies, with wind directions being the main factor affecting TF in different radial directions. Yuan et al. (2019) described the branch SF variability of C. korshinskii and Salix psammophil, and they showed that intra-event branch SF variability of xerophytic shrubs temporally depended on rainfall characteristics, with longer lag times and a greater rainfall amount required to initiate branch SF for C. korshinskii compared to S. psammophila. It can be found that those studies on temporal dynamics of shrub rainfall partitioning only explored the single-element process (i.e., TF or SF), and ignored IC. Concurrent investigations of all rainfall partitioning components and the associated influencing factors at the intra-event scale have rarely been reported. Furthermore, to the best of author's knowledge, no previous studies have been reported so far that simultaneously analyzed TF, SF, and IC on an intra-event scale in any shrub species. Therefore, a detailed understanding of shrub rainfall partitioning dynamics at the intra-event scale with high-resolution data is sorely needed to improve mechanistic understanding of shrubs' eco-hydrological role in shaping and sustaining drylands.

This study was designed at the event and process scales to investigate inter-event and intra-event rainfall partitioning variability, based on field measurements of two dominant xerophytic shrubs (C. korshinskii and S. psammophila) during the rainy seasons of 2014–2015 in the Loess Plateau of China. This study integrated the inter-event and intra-event dynamics of rainfall partitioning by combining TF, SF, and IC at the individual plant scale. We mainly seek to (a) compare the dynamic processes of rainfall partitioning between the two shrubs at both inter-event and intra-event scales, and (b) elucidate the effects of rainfall characteristics and vegetation structure characteristics on rainfall partitioning at both scales. Such an improvement in our understanding of the fine-scale mechanism of rainfall partitioning would offer valuable insights regarding shrub–water interactions.

2.1 Site description and experimental design

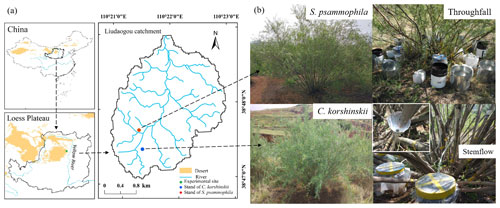

This study was carried out in the Liudaogou catchment (110∘21′–110∘23′ E, 38∘46′–38∘5′ N) in Shenmu County, Shaanxi Province of China (Fig. 1a). The Liudaogou catchment (6.9 km2, altitude from 1094 to 1273 m) is located between the northern Loess Plateau and the southern fringe of Mu Us sandy land in North China. This region is characterized by a moderate temperate continental climate with well-defined rainy and dry seasons. The mean annual rainfall is 437 mm, ranging between 109–891 mm (1971–2013), and the potential evaporation is 1337 mm yr−1 (Jia et al., 2013). Approximately 70 %–80 % of the rainfall events are concentrated in the warm months between July and September, and most of them occur in the form of torrential rain (Yang et al., 2019). The Liudaogou catchment was characterized by the natural arid shrub-steppe before it was artificially vegetated in the past 20 or 30 years for soil and water conservation, windbreaks, and sand fixation. The main land-use types include artificial grassland, artificial shrub, and farmland, and the main vegetation species are Stipa bungeana, C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, which are widely distributed in the arid and semiarid areas of northwestern China (Yuan et al., 2019). The shrubs are distributed sparsely with distinct interspaces. The actual ground-cover fraction covered by shrub canopies was less than 20 %, with the rest of the soil being directly exposed to rainfall.

Two representative xerophytic shrubs, C. korshinskii and S. psammophila (20 years old), were used for the study. Both species are multi-stemmed deciduous perennial shrubs with inverted cone crowns and without trunks. They have minimal nutrient requirements, extensive adaptability, and strong stress resistance, making them superior in adapting to resource-poor environments. According to the documentation of Flora of China (Chao and Gong, 1999; Liu et al., 2010) and field observations, S. psammophila has an odd number of strip-shaped leaves with 2–4 mm in width and 40–80 mm in length, and C. korshinskii has pinnate compound leaves arranged oppositely or sub-oppositely with 6–10 cm in length, and each pinna has 5 to 8 pairs of ovate leaflets (7–8 mm in length and 2–5 mm in width). We established two plots (one for C. korshinskii and the other for S. psammophila) at the southwestern catchment for field observation (Fig. 1a). The two plots share similar stand conditions, with the sizes of 3294 and 4056 m2, elevations of 1179 and 1207 m, and slopes of 13 and 18∘, respectively. The distance between the two plots do not exceed 1.5 km.

2.2 Field measurements

2.2.1 Measurements of rainfall and meteorological factors

This study focused on the individual shrub rainfall partitioning of C. korshinskii and S. psammophila during the 2014–2015 rainy seasons. Gross rainfall was measured using one tipping-bucket rain gauge (TBRG) with a 0.2 mm resolution (with 186.3 cm2 collection area) (Onset® RG3-M, Onset Computer Corp., USA) in an open area (Fig. 1b). The rainfall characteristics, e.g., rainfall amount (RA, mm), rainfall duration (RD, h), rainfall interval (RI, h), average rainfall intensity (I, mm h−1), rainfall intensity at 10 min interval (i.e., 0–10 min, 10–20 min, …) since the start of rainfall (I10, mm h−1) were calculated accordingly. For I10, the one after the onset of rainfall is defined as I10_b (mm h−1), i.e., the rainfall intensity in the first 10 min. The maximum I10 during the rainfall process is defined as I10_max (mm h−1). Since TBRG has a resolution of 0.2 mm, we define a single rainfall event as one that is greater than 0.2 mm and not raining for at least 4 h apart (Iida et al., 2012). A meteorological station was set up at the experimental plot to record wind speed (WS, m s−1) and wind direction (WD, ∘) (Model 03002, R. M. Young Company, Traverse City, Michigan, USA), air temperature (T, ∘C) and relative humidity (H, %) (Model HMP 155, Vaisala, Helsinki, Finland). Data were measured every 30 s and averaged at 10 min intervals by the data logger (Model CR1000, Campbell Scientific, Inc., USA).

2.2.2 Measurements of vegetation characteristics

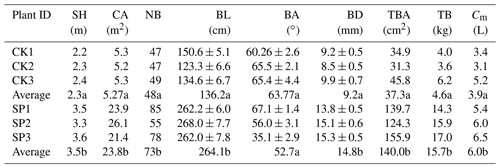

Three representative shrub plants with similar crown heights and crown areas were selected in each shrub species (Table 1). Based on plot investigation, the vegetation traits at the scale of single plant and branch were measured. For each plant, we measured shrub height (SH, m) with a graduated telescopic stick, counted the number of branches (NB), and calculated the projected canopy area (CA, m2) by measuring canopy diameter following the south–north and east–west direction. The total number of branches was 143 and 218 for selected C. korshinskii and S. psammophila plants, respectively. For each branch, we measured branch length (BL, cm) with a measuring tape, branch angle (BA, ∘) with a pocket geologic compass, and branch diameter (BD, mm) with a vernier caliper to calculate the total basal area of the shrub (TBA, m2). Thus, four BD categories (0–10, 10–15, 15–20 and > 20 mm) were defined to ensure the appropriate branch amounts within each category. The measured vegetation traits of C. korshinskii and S. psammophila plants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1Descriptive statistics (mean ± SE) of canopy morphology of C. korshinskii (CK1–CK3) and S. psammophila (SP1–SP3) plants. Values are mean ± SD.

Note: SH: shrub height; CA: canopy area; NB: number of branches; BL: branch length; BA: branch angle; BD: branch diameter; TBA: total basal area of the shrub; TB: total dry aboveground biomass; Cm: total canopy storage per plant. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between two species (p < 0.05).

Water storage capacity of the canopy is a key factor in determining the amount of IC (Levia and Herwitz, 2005; Garcia-Estringana et al., 2010) and SF yield (Van Stan et al., 2020). We selected 10 representative branches for each shrub species outside the stands, to determine the canopy water storage capacity (C, mL g−1) using water immersion method, which was widely used in previous studies (Garcia-Estringana et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012). The C was calculated as the difference between saturated weight and fresh weight divided by the dry biomass of the selected branch. The C. korshinskii and S. psammophila had a C of 0.85 and 0.38 mL g−1, respectively. In addition, we estimated the total dry aboveground biomass of single plant (TB) for each species according to the allometric growth model developed by Yuan et al. (2016, 2017) in the same study area. The allometric growth model had very high accuracy with R2 more than 0.92. The total canopy water storage of single plant (Cm= TB times C) was calculated to represent the amount of rainfall absorbed by the shrub canopy during the rainfall event (Table 1).

2.2.3 Measurements of inter-event rainfall partitioning

Manual rain gauges (314.12 cm2 collection area) were used to measure event TF at eight radial directions (E, SE, S, SW, W, NW, N, NE) beneath each shrub canopy (Fig. 1b). For C. korshinskii, eight TF gauges were placed under each C. korshinskii plant with a 50 cm distance from the base of stems in the eight directions. For S. psammophila, 20 TF gauges were placed under each plant, with 12 of them placed in 50, 100, and 150 cm distances from the base of stems in 4 directions (E, S, W, and N), and 8 of them placed in 75 and 125 cm distances in the other 4 directions (SE, SW, NW, and NE). If the rainfall ended during the daytime, we completed the collection of TF samples within 2 hours after the end of rainfall. If the rainfall ended at night, we completed the collection of samples as early as possible the next day to minimize evaporation.

A total of 53 branches of C. korshinskii (17, 21, 7, and 8 for BD categories of 0–10, 10–15, 15–20, and > 20 mm, respectively) and 98 branches of S. psammophila (20, 30, 20, and 28 for BD categories of 0–10, 10–15, 15–20, and > 20 mm, respectively) were used to determine SF yield, which covered different types of branches. Funnels consisting of flexible aluminum foil plates were used to collect SF (Fig. 1b). The funnel was fixed to each branch near the base and sealed with neutral silicone caulk, and a 0.5 cm diameter PVC hose was attached vertically to transport SF from the funnel to a container with a lid (SF gauges) with minimum travel time.

2.2.4 Measurements of intra-event rainfall partitioning

Among the selected plants, one C. korshinskii and one S. psammophila plant were selected to record the volume and timing of TF and SF with TBRGs at intra-event scale. A TBRG was installed in each of the four radial directions (E, S, W, N) beneath the shrub canopy of each species, to measure the temporal variations of TF within the rainfall event (Fig. 1b). To characterize intra-event SF dynamics, six representative branches of different BD categories were selected for each species, using the following selection criteria: no crossover between the experimental branch and adjacent branches, no inflection point from the tip to the base of the branch, and accessibility for easy installation and measurement. These branches were distributed across the four BD categories (0–10, 10–15, 15–20, and > 20 mm, respectively). The SF TBRGs were covered with polyethylene films to prevent the accessing of TF and splash (Fig. 1b). Unfortunately, some TBRGs lost a substantial amount of SF data and were therefore discarded from the analysis. Four branches were finally identified for each species, located in each of the four BD categories to measure intra-event SF (6.7, 13.5, 18.6, and 22.1 mm for C. korshinskii and 7.2, 14.4, 18.2, and 31.3 mm for S. psammophila).

2.3 Rainfall partitioning calculations

2.3.1 Inter-event rainfall partitioning calculations

For each individual shrub, we measured the TF volume for each TF gauge, averaged them, and then converted the volume into TF depth (TFd, mm) at each rainfall event. The percentage of TF (TF %, %) was calculated by dividing TFd by RA, and the average TF intensity (TFI, mm h−1) was calculated by dividing TFd by the TF duration (TFD, h). The TFD was recorded by TF TBRGs.

The inter-event SF yield was defined as the total SF volume of a single plant in a rainfall event. The SF volumes measured on the selected branches were averaged to obtain the average volume of SF on the branch scale, which multiply the number of branches to obtain the total SF volume from the plant. The shrub-scale SF-equivalent water depth (SFd, mm) and the average SF intensity (SFI, mm h−1) were calculated. The percentage of SF (SF %, %) was converted by dividing SFd by RA. The SFd and SFI were calculated by the following equations (Hanchi and Rapp, 1997; Levia and Germer, 2015):

where (ml) is the average volume of SF on the branch scale, n is the number of branches of an individual plant, CA (m2) is the canopy area of an individual plant, TBA (cm2) is the total basal area of an individual plant, and SFD is SF duration (h) recorded by SF TBRGs. The parameters, 1000 and 10, are the unit-conversion factors.

The IC depth (ICd, mm) and percentage of IC (IC %, %) were estimated as

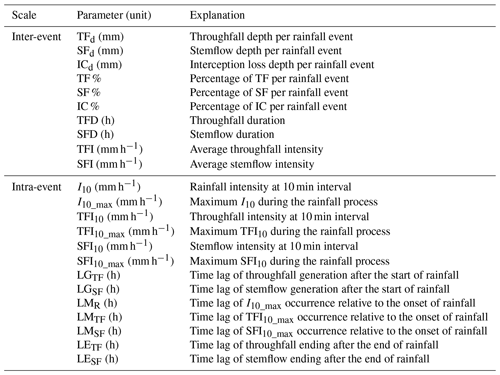

The above inter-event rainfall partitioning variables and their explanations are summarized in Table 2.

2.3.2 Intra-event rainfall partitioning calculations

The TF and SF volume and timing within rainfall events were automatically recorded at dynamic intervals between neighboring TBRG tips (0.2 mm). To better reflect fluctuations in rainfall partitioning components, the intra-event TF and SF data were aggregated every 10 min to match the recording interval of gross rainfall. The four TFd recorded by TBRGs were averaged to obtain the average TFd at 10 min interval (TFd10, mm). The TFI at 10 min interval (TFI10, mm h−1) was calculated by dividing the TFd10 by the 10 min. Meanwhile, SFd and SF intensity at 10 min interval (SFd10, mm, and SFI10, mm h−1, respectively) were calculated as

where SFRG,j (mm) is SFd of the selected jth branch category recorded by TBRG at 10 min interval ( h), nj is the number of branches in the jth category of a single plant, 4 is the number of the BD category (0–10, 10–15, 15–20, and > 20 mm), and 186.3 (cm2) is the collection area of TBRG. The product of SFRG,j and 186.3 is the SF volume from the branch. The parameter 100 is the unit-conversion factor.

Based on the calculated TFI10 and SFI10, the maximum TFI and SFI at 10 min interval (TFI10_max and SFI10_max, respectively, mm h−1) of each rainfall event can be determined. The descriptive variables for the intra-event rainfall partitioning also include the lag times of TF or SF corresponding to the rainfall event. Based on the temporal data recorded by TBRGs (between neighboring tips), the following variables were calculated: LGTF and LGSF (h), the time lag of TF and SF generation after the start of rainfall, respectively; LMTF, LMSF and LMR (h), the time lag of TFI10_max, SFI10_max and I10_max relative to the onset of rainfall, respectively; and LETF and LESF (h), the time lag of TF and SF ending after the end of rainfall. The intra-event rainfall partitioning variables and their explanations are summarized in Table 2.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Independent-samples t tests were used to analyze differences in rainfall partitioning parameters between C. korshinskii and S. psammophila at both inter-event and intra-event scales. To detect the effects of meteorological factors on rainfall partitioning, Pearson correlation analysis was used to test the significance between rainfall partitioning parameters and meteorological factors at the two scales. The significant correlated factors were double-checked by partial correlation analysis to determine their individual effects on rainfall partitioning components. Stepwise regression of these indicators was performed by analytical tests at the 0.05 level of significance to select the most influential factors on rainfall partitioning variables at inter-event and intra-event scales, and the corresponding quantitative relationships were established based on a qualifying level of significance (p < 0.05) and the highest coefficient of determination (R2). Significance levels were set at 95 % confidence intervals. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 21.0, Origin 2018, and Microsoft Excel 2019.

3.1 Inter-event variations of rainfall partitioning

3.1.1 Characteristics of inter-event rainfall partitioning variables

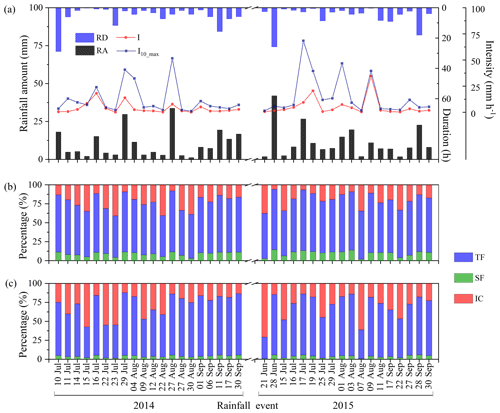

A total of 38 rainfall events were recorded for rainfall partitioning measurements, including 20 events (215.4 mm) in 2014 and 18 events (205.6 mm) in 2015, which accounted for 75.2 % and 75.0 % of total RA during the experimental period in 2014 and 2015, respectively (Fig. 2a). The RA ranged from 1.2 to 41.9 mm with an average of 11.1 ± 8.8 mm (mean ± SD). In general, rainfall events were unevenly distributed in terms of RA. Approximately 34.2 % of rainfall events were smaller than 5 mm, 26.3 % within 5–10 mm, 26.3 % within 10–20 mm, and 13.2 % larger than 20 mm, representing 8.8 %, 17.5 %, 36.3 %, and 37.4 % of the total RA amount, respectively (Fig. 2a). The average I varied from 0.2 to 35.1 mm h−1 with an average of 6.0 ± 1.3 mm h−1, and approximately 76.3 % of the events was < 5 mm h−1, 13.2 % was 5–10 mm h−1, and 10.5 % was > 10 mm h−1. The I10_max ranged from 1.2 to 68.4 mm h−1 with an average of 13.7 ± 2.7 mm h−1, and approximately 42.1 % of the events was < 5 mm h−1, 23.7 % was 5–10 mm h−1, and 34.2 % was > 10 mm h−1. The RD ranged from 0.2 to 28.9 h and averaged 5.3 ± 1.0 h. The RD of most rainfall events was less than 5 h (68.4 %), and only 5 rainfall events had RD greater than 10 h.

Figure 2(a) Individual rainfall amount (RA) (n= 38), rainfall duration (RD), average rainfall intensity (I, mm h−1), maximum rainfall intensity at 10 min interval (I10_max, mm h−1); and rainfall partitioning into TF %, SF %, and IC % of (b) C. korshinskii and (c) S. psammophila.

The TFd for C. korshinskii ranged from 0.7 to 31.2 mm (coefficient of variation, CV = 87.5 %) with corresponding TF % ranging from 54.0 % to 80.3 % (CV = 10.6 %) across the 38 events (Fig. 2b). The TFd values for S. psammophila were 0.4–33.4 mm (CV = 96 %) and 28.5 %–82.7 % (CV = 21.5 %), respectively (Fig. 2c). The SFd for C. korshinskii ranged from 0.04 to 6.1 mm (CV = 106.6 %), with corresponding SF % of 2.0 %–14.5 % (CV = 34.2 %) (Fig. 2b). The comparable SFd values for S. psammophila varied from 0.01 to 2.2 mm (CV = 98.6 %) and 0.7 %–5.9 % (CV = 38.9 %), respectively (Fig. 2c). The ICd values for C. korshinskii varied from 0.5 mm to 2.9 mm (CV = 43.9 %), with corresponding IC % of 5.7 %–40.8 % (CV = 47.3 %) (Fig. 2b), and the comparable values were 0.8–5.7 mm (CV = 44.8 %) and 12.1 %–70.8 % (CV = 53.3 %) for S. psammophila, respectively (Fig. 2c). For C. korshinskii, TF represented the largest component of all rainfall events, while for S. psammophila, SF represented the smallest component of all rainfall events (Figs. 2b and c).

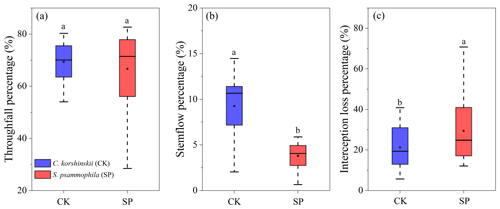

The TF %, SF %, and IC % in rainfall partitioning between the two species are shown in Fig. 3. There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in average TF % between C. korshinskii (69.4 ± 7.4 %) and S. psammophila (66.7 ± 14.6 %). The SF % was significantly higher (p < 0.05) for C. korshinskii (9.2 ± 3.2 %) than for S. psammophila (3.8 ± 1.5 %) (Fig. 3b). The IC % was significantly lower (p < 0.05) for C. korshinskii (21.4 ± 10.2 %) than for S. psammophila (29.5 ± 15.9 %) (Fig. 3c). The variations of TF % and IC % among the rainfall events were greater for S. psammophila, but that of SF % was smaller compared to C. korshinskii (Fig. 3).

Figure 3Boxplots of (a) TF %, (b) SF %, and (c) IC % for C. korshinskii (CK) and S. psammophila (SP). The horizontal thick black line indicates the median, boxes correspond to the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers represent values that fall within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Mean values are represented with the black square. Different letters indicate significant differences between the two species (p < 0.05).

3.1.2 Relationships between inter-event rainfall partitioning variables and meteorological factors

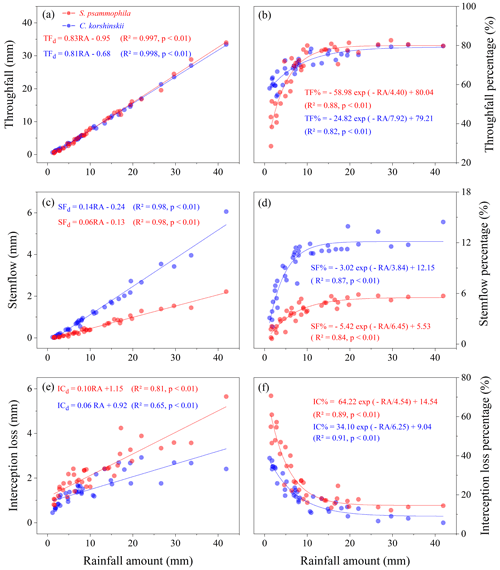

Correlation analysis indicated that meteorological factors had a similar effect on rainfall partitioning for the two species. Stepwise regression analysis identified that the SF parameters (SFd and SF %), TF parameters (TFd and TF %) and IC parameters (ICd and IC %) were all mainly controlled by RA. Following RA, the influences of rainfall intensity (I, I10_max) were also significant (p < 0.05). However, the other meteorological factors (RD, RI, WS, WD, T, H) had no significant effect on rainfall partitioning (p > 0.05).

Significantly positive and linear relationships were found between TFd and RA for both C. korshinskii and S. psammophila (Fig. 4a). According to the regression equations, the threshold of RA for TF generation was 0.8 and 1.1 mm for C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, respectively. The TF % increased with increasing RA as an exponential function (Fig. 4b). When RA reached 20 mm, the increasing of TF % stabilized, and TF % of C. korshinskii and S. psammophila reached 79.2 % and 80.0 %, respectively. The SFd also had a significantly positive and linear relationship with RA for the two species (Fig. 4c). When RA was greater than 1.7 and 2.2 mm, C. korshinskii and S. psammophila began to produce SF, respectively. The SF % increased exponentially with increasing RA, and SF % of C. korshinskii was always higher than that of S. psammophila. The SF % tended to be approximately constant at 12.2 % and 5.5 % as RA ≥ 20 mm for C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, respectively (Fig. 4d). The ICd was also positively correlated with RA (Fig. 4e). However, IC % decreased exponentially with incremental RA, and IC % of S. psammophila was always higher than that of C. korshinskii (Fig. 4f). When RA reached 20 mm, IC % tended to be approximately constant at 9.0 % and 14.5 % for C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, respectively.

3.2 Intra-event variations of rainfall partitioning

3.2.1 Characteristics of intra-event rainfall partitioning variables

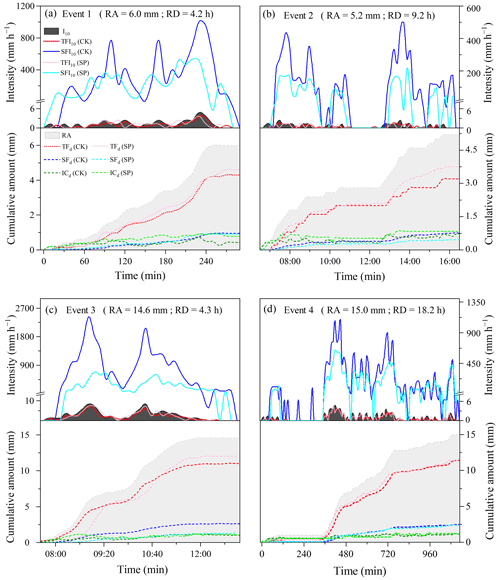

The intra-event TF and SF were well synchronized with the rainfall process, in terms of the shape, number, and location of the intensity peaks for both C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, which were vividly demonstrated at the four representative rainfall events in Fig. 5. The SF intensity (SFI10) was much higher than TF intensity (TFI10) and rainfall intensity (I10) for both C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, whereas TFI10 was less than or equal to I10. As expected, IC was the main component at the initial stage of rainfall, and then TF was the major component (≥ 50 %) for rainfall partitioning (Fig. 5). The TF and SF generation thresholds measured using the TBRGs were 0.4 ± 0.2 and 1.0 ± 0.7 mm for C. korshinskii, and 0.3 ± 0.1 and 0.7 ± 0.3 mm for S. psammophila, respectively. They were expected to both be smaller than the thresholds derived from the regression equation between TFd (or SFd) and RA mentioned previously, which assume that TF and SF start after the canopy is fully wet. This further demonstrates the importance of high-resolution data in rainfall partitioning studies.

Figure 5Time series (10 min interval) of rainfall partitioning within four rainfall events for C. korshinskii (CK) and S. psammophila (SP). Events 1–4 occurred on 3 August, 17 September, 28 September, and 30 September in 2015, respectively. The solid lines represent the intensities of rainfall (I10), TF (TFI10), and SF (SFI10) at 10 min interval. The dotted lines indicate the accumulated amount of RA, TF, SF, and IC.

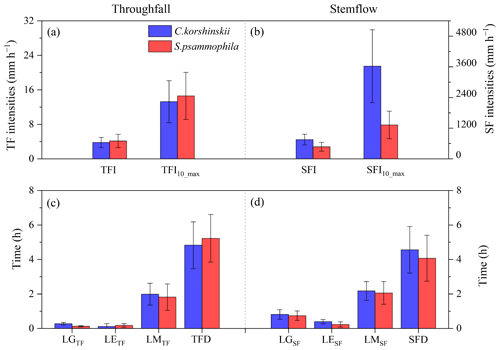

Figure 6 describes the difference in average intra-event TF and SF variables between C. korshinskii and S. psammophila. Although there were no statistically significant differences between the two species in intensities, durations, or the lag time of TF and SF, some trends were observed. The TFI and TFI10_max of both species were similar to I (6.0 ± 1.3 mm h−1) and I10_max (13.7 ± 2.7 mm h−1), respectively. In contrast, SFI and SFI10_max were significantly greater than I and I10_max, respectively. Specifically, TFI and TFI10_max of C. korshinskii were 3.8 ± 1.2 and 13.3 ± 4.9 mm h−1, respectively, which were slightly lower than that of S. psammophila (4.3 ± 1.5 and 14.6 ± 5.5 mm h−1, respectively) (Fig. 6a). The SFI and SFI10_max of C. korshinskii (753.8±208.0 and 3627.2 ± 1424.7 mm h−1, respectively) were higher than those of S. psammophila (471.2 ± 170.2 and 1424.8 ± 538.3 mm h−1, respectively) (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6Intra-event TF (a, c) and SF (b, d) variables of C. korshinskii and S. psammophila. All the variables are explained in Table 2.

Furthermore, a time lag was usually observed between the onset of rainfall and the generation of TF (LGTF) and SF (LGSF). Similarly, there is a time lag between rainfall and TF or SF in terms of the time to reach maximum intensity (LM) and the time to end (LE). The S. psammophila had a shorter lag time than C. korshinskii in terms of TF (LGTF: 0.1 ± 0.04 vs. 0.3 ± 0.1 h) and SF production (LGSF: 0.7 ± 0.3 vs. 0.8 ± 0.3 h), and their time to reach maximum intensity (LMTF: 1.8 ± 0.8 vs. 2.0±0.6 h; LMSF: 2.1 ± 0.7 vs. 2.2 ± 0.5 h) (Fig. 6c and d). However, the S. psammophila had longer TFD (5.2 ± 1.4 vs. 4.8±1.4 h) and LETF (0.2 ± 0.1 vs. 0.1 ± 0.1 h) than C. korshinskii (Fig. 6c). Conversely, the SFD and LESF in C. korshinskii (4.6 ± 1.4 and 0.4 ± 0.1 h, respectively) were longer than those in S. psammophila (4.1 ± 1.3 and 0.2 ± 0.2 h, respectively) (Fig. 6d). The above differences in TF and SF variables indicate that S. psammophila should be more conducive to generate TF than C. korshinskii, while C. korshinskii should be more conducive to produce SF than S. psammophila.

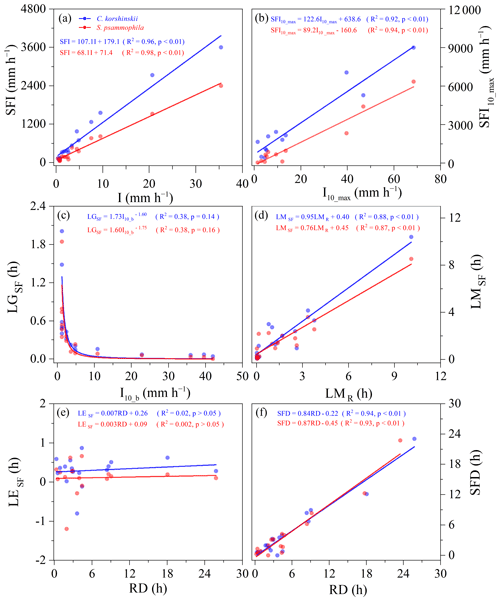

3.2.2 Relationships between intra-event rainfall partitioning variables and meteorological factors

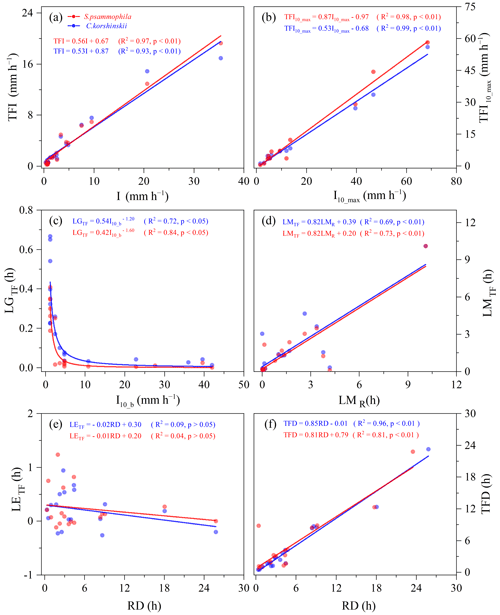

Similar relationships existed between intra-event rainfall partitioning variables and meteorological factors for two species. For both shrubs, rainfall intensity (I, I10_max, and I10_b) and RD were the main influencing factors affecting intra-event TF variables (Fig. 7) and SF variables (Fig. 8). While the effects of other meteorological factors (RD, RI, WS, WD, T, H) on TF and SF variables within the event were not significant (p > 0.05). The TFI, TFI10_max, LMTF, and TFD were linearly correlated with I, I10_max, LMR, and RD, respectively, while LGTF was power correlated functionally with I10_b (p < 0.05). The TF intensities (TFI and TFI10_max) of S. psammophila increased faster with rainfall intensities (I and I10_max) than that of C. korshinskii. The SFI, SFI10_max, LMSF, and SFD were also linearly correlated with I, I10_max, LMR, and RD, respectively (p < 0.05). The LGSF was power correlated functionally with I10_b (p= 0.14 and p= 0.16 for C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, respectively), which was weaker than the correlation between LGTF with I10_b. The SF intensities (SFI and SFI10_max) of C. korshinskii increased with rainfall intensities (I and I10_max) more rapidly than that of S. psammophila. However, for both species, there was no significant relationship between LETF or LESF and RD (Figs. 7 and 8). The above results indicate that the intra-event rainfall partitioning variables largely dependent on I and RD.

Figure 7Relationships of intra-event throughfall (TF) variables with meteorological characteristics for C. korshinskii and S. psammophila. All the variables are explained in Table 2.

4.1 Rainfall partitioning and influencing factors at inter-event scale

This study indicated that SF % of C. korshinskii (9.2 %) was significantly higher than that of S. psammophila (3.8 %) (Fig. 3), which was comparable to the value of 10.4 % and 6.3 % reported by Yang et al. (2019) for the same species in similar semiarid regions of China. Under the same rainfall regimes, the difference in vegetation characteristics is the main reason for the difference in SF (Yuan et al., 2017; Whitworth-Hulse et al., 2020a; Yue et al., 2021). Comparing the structural properties of two shrubs with the same age (20 years), we found that CA, BD, BL, BA and NB values of S. psammophila were 4.51, 1.61, 1.94, 0.83 and 1.52 times the values of C. korshinskii, respectively (Table 1). On the branch scale, C. korshinskii had more small and short branches, but larger BA than that of S. psammophila, which contributed to SF generation. Yuan et al. (2016) concluded that a beneficial branch architecture for SF production should include more relatively small branches and larger BAs, and SF productivity decreased with the BD size of branches. Furthermore, C. korshinskii had a smaller CA, and a larger SFd than S. psammophila under the same SF volume. Somewhat in line with Yuan et al. (2016) and Yue et al. (2021), our results suggest that a beneficial branch architecture for SF production of C. korshinskii should include relatively small CA, BD, BL and large BA (Table 1).

Leaf traits were reported to exert a significant influence on rainfall partitioning (Garcia-Estringana et al., 2010; Magliano et al., 2019a). According to the documentation in Flora of China (Liu et al., 2010), C. korshinskii has pinnate compound leaves and each pinna has 5 to 8 pairs of ovate leaflets, and the leaves are lanceolate and concave, and the surface is densely sericeous. In comparison, S. psammophila has striped or striped oblanceolate leaves, which are margin revolute, and the upper surface of mature leaf blade is almost glabrous (Chao and Gong, 1999). The branches of both shrubs are smooth, with a more developed cuticle layer on the surface of the S. psammophila branches, while the C. korshinskii branches contain oil and have waxy skin (Chao and Gong, 1999; Liu et al., 2010). The leaf morphology and epidermal characteristics of branches of C. korshinskii were more beneficial for SF generation than that of S. psammophila (Whitworth-Hulse et al., 2020b; Yuan et al. 2017). It was found that big biomass of leaves, concave leaf shape and leaf pubescence are beneficial to promote the generation of SF (Yuan et al., 2016). These factors together enable the leaves to function as a highly efficient natural water collecting system.

The mean IC % of C. korshinskii (21.4 %) was significantly lower than that of S. psammophila (29.5 %) in this study. The intercepts in the fitted formulas between IC and RA in Fig. 4e indicated that C. korshinskii (0.92 mm) had a lower canopy water storage than S. psammophila (1.15 mm), hence the potential IC of C. korshinskii was lower. Zhang et al. (2017) reported that IC % were higher in the Hippophae rhamnoides stand (24.9 %) than in the Syringa pubescens stand (19.2 %), which was mainly attributed to the lower canopy water storage of S. pubescen. This study was done at the shrub scale, so we compared the total canopy water storage of individual plant (Cm), and we found that Cm of S. psammophila (6.0 L) was significantly higher than that of C. korshinskii (3.9 L) (Table 1). This was mainly due to the significantly higher average total dry aboveground biomass of S. psammophila (15.7 kg per plant) than C. korshinskii (4.6 kg per plant). Consequently, individual S. psammophila absorbed more rain water to moisten the branches and leaves than that of individual C. korshinskii, which could explain higher IC % of S. psammophila than C. korshinskii. Thus, the best predictors for IC were biomass-related parameters (i.e., woody biomass and total biomass) (Li et al., 2016).

4.2 Rainfall partitioning and influencing factors at the intra-event scale

Temporal heterogeneity of rainfall clearly influences the amount and timing of TF and SF reaching the soil under the canopy, as explained by some previous intra-event rainfall partitioning studies from forested ecosystems (Owens et al., 2006; Levia et al., 2010; Molina et al., 2019). Our experiment investigated the intra-event dynamics of all rainfall partitioning components in xerophytic shrubs, which has scarcely been reported before. Our results showed that the temporal dynamics of TF and SF under the shrub canopy almost matched the dynamics of rainfall (Fig. 5). It agreed with the reports of Zhang et al. (2018) and Yuan et al. (2019) who demonstrated the temporal synchronization of TF and SF with rainfall, respectively. The SFI is generally greater than I for different species (Fig. 6), which can influence ecohydrological processes such as groundwater recharge, erosion, and overland flow (Spencer and van Meerveld, 2016). The SF converges substantial rainwater to the shrub bases and then delivers it into the soil as a point input to recharge soil moisture and nutrient enrichment (Germer et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011; Cayuela et al., 2018; Jian et al., 2019). Moreover, as SF water is funneled belowground along roots of the shrubs (Martinez-Meza and Whitford, 1996; Li et al., 2009), we suggest that changes in SF inputs explain, at least in part, the temporal variation in subsurface moisture patterns.

The intensity variables and lag time of SF and TF relative to rainfall were the key to describe the intra-event rainfall partitioning (Fig. 6). The effects of meteorological factors on SF and TF variables at the intra-event scale were derived from multiple regression analysis in this study. The SF and TF variables (intensity and temporal dynamics) were strongly influenced by rainfall intensity (e.g., I, I10_max and I10_b) and duration (e.g., RD and LMR). This is consistent with the results reported by Yuan et al. (2019), who indicated that there was a significant effect of rainfall intensity on the SF process of C. korshinskii. The main factors affecting intra-event SF and TF variables were the same, but the effects were still slightly different between the two shrubs. Under the same rainfall intensity, the average TFI under the canopy of S. psammophila was higher than C. korshinskii (Fig. 7a and b). But the average SFI of C. korshinskii was greater than S. psammophila at shrub scale (Fig. 8a and b), which was also found for the branch SFI reported by Yuan et al. (2019). In addition to the inter-shrub differences, the effects of I10_b on LGTF and LGSF were slightly different. The correlation between LGSF and I10_b (Fig. 8c) was weaker than that between LGTF and I10_b (Fig. 7c). This may be due to the fact that TF has two components, i.e., free TF and released TF (Staelens et al., 2008; Levia et al., 2017; Van Stan et al., 2020), and that SF only starts to produce when a certain amount of rainfall is reached (Germer et al., 2010; Levia et al., 2010; Dunkerley, 2014; Yuan et al., 2019). Our results indicated that S. psammophila had dynamic characteristics (e.g., larger TFI, TFI10 and LETF as well as TFD, and shorter LGTF and LMTF) producing larger TF depth (TFd = TFI ⋅ TFD) (Fig. 6a and c), while C. korshinskii had dynamic characteristics (e.g., larger SFI, SFI10 and LESF as well as SFD) producing larger SF depth (SFd = SFI ⋅ SFD) (Fig. 6b and d).

The vegetation characteristics have an important effect on the dynamics and the lag time of TF and SF (Yuan et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2018). Based on the temporal data recorded by TBRGs, we found that C. korshinskii produced TF and SF later than S. psammophila (Figs. 5 and 6), which was also reported by Yuan et al. (2019) for branch SF of the same species. We inferred that this was due to the higher canopy water storage capacity of C. korshinskii (0.85 mL g−1) compared to S. psammophila (0.38 mL g−1). However, when the branches were moistened, SF production of C. korshinskii was greater than that of S. psammophila because of its branch and leaf characteristics, as discussed in Sect. 4.1 (Fig. 5). It was found that the great bark water storage capacity of forests could result in the further delay of TF and SF onset (Levia and Herwitz, 2005; Levia et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016; Pinos et al., 2021). In summary, the different intra-event TF and SF dynamics between species were attributed to a complex interaction of biotic and abiotic factors (Yuan et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2018; Levia et al., 2010).

4.3 Implications and further scopes

Most of the previous rainfall partitioning investigations for shrubs were limited at the inter-event scale or only focused on TF or SF at intra-event scale. The intra-event rainfall partitioning dynamics, which could help to provide a better understanding of soil water replenishment and its distribution in soil and the key ecohydrological cycle in drylands, have been rarely explored. This study presents the first investigation of all the rainfall partitioning components (i.e., TF, SF, and IC) for shrubs at both inter- and intra-event scales, providing a full view of the reciprocal dynamics among IC, TF, and SF at the shrub scale. This is the main novelty and a step forward compared to the previous related studies. We have also obtained the quantitative relationship between rainfall partitioning variables and rainfall characteristics and further elaborated the influence of vegetation structure characteristics (leaf, canopy structure, biomass, etc.) on rainfall partitioning. The newly obtained insights help to understand the fine characterization of shrub-dominated ecohydrological processes, and improve the accuracy of water balance estimation in dryland ecosystem.

There are several issues that need further investigation. Firstly, long-term observations of rainfall partitioning dynamics for more shrub plants and species are needed, and the rainfall partitioning models should be developed for shrubs. Every component of shrub canopy water balance, including canopy evaporation loss and transpiration should be considered. Secondly, the effects of rainfall partitioning on soil moisture dynamics, nutrient cycling, and plant transpiration should be substantially investigated. How the shrubs actually make use of small amounts of TF or SF should be examined to detect the interactions between water redistribution and vegetation physiological processes. Finally, the extension from the individual plant to stand and larger scales remains a challenging topic for rainfall partitioning, which can help to improve understanding the role of rainfall partitioning in the regional hydrologic cycle.

In this study, we analyze the rainfall partitioning and the influences of bio-/abiotic factors of two typical shrubs at both inter- and intra-event scales in the Loess Plateau. To ensure a larger proportion of the rainfall is allocated under the canopy, two species can obtain more net rainfall through different mechanisms. At the event scale, there was no significant difference in TF % between the two shrubs, but C. korshinskii had significantly higher SF % and lower IC % compared to S. psammophila. At the intra-event scale, TF and SF of two shrubs were well synchronized with the rainfall, but C. korshinskii had the advantage of SF production, while S. psammophila had the advantage of TF generation. For both shrubs, the inter-event rainfall partitioning amount and percentage depended more on RA, and I and RD controlled the intra-event TF and SF variables. The C. korshinskii has larger BAs, more small branches and smaller CAs to produce SF more efficiently, and S. psammophila has larger biomass to intercept more RA. These findings could enhance our understanding of TF and SF dynamics and corresponding driving factors at inter- and intra-event scales, and help in modeling the critical ecohydrological processes in arid and semiarid regions.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

JA was responsible for the data investigation, analysis, and methodology and completed the original draft of the article. GG conceptualized this research, including conceptualization and methodology, and participated in the review and editing of the writing. CY contributed to the data investigation and the review and editing of the writing. JP and BF were involved in writing review and editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Special thanks are given to Shenmu Erosion and Environment Research Station for experimental support to this research. We thank David Dunkerley and two anonymous reviewers and the managing editor Lixin Wang for their positive feedback and professional comments which greatly improved the quality of this paper.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 41991233 and 41822103) and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. Y202013).

This paper was edited by Lixin Wang and reviewed by David Dunkerley and two anonymous referees.

Cayuela, C., Llorens, P., Sanchez-Costa, E., Levia, D. F., and Latron, J.: Effect of biotic and abiotic factors on inter- and intra-event variability in stemflow rates in oak and pine stands in a Mediterranean mountain area, J. Hydrol., 560, 396–406, 2018.

Chao, P. N. and Gong, G. T.: Salix (Salicaceae), in: Flora of China, edited by: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H., and Hong, D. Y., Science Press, Beijing and Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis, 162–274, http://www.iplant.cn/info/Salix?t=foc (last access: 21 July 2022), 1999.

Chesson, P., Gebauer, R. L., Schwinning, S., Huntly, N., Wiegand, K., Ernest, M. S., Sher, A., Novoplansky, A., and Weltzin, J. F.: Resource pulses, species interactions, and diversity maintenance in arid and semi-arid environments, Oecologia, 141, 236–253, 2004.

Chu, X., Han, G., Xing, Q., Xia, J., Sun, B., Yu, J. B., and Li, D.: Dual effect of precipitation redistribution on net ecosystem CO2 exchange of a coastal wetland in the Yellow River Delta, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 249, 286–296, 2018.

Dunkerley, D.: Stemflow production and intrastorm rainfall intensity variation: an experimental analysis using laboratory rainfall simulation, Earth. Surf. Proc. Land., 39, 1741–1752, 2014.

Garcia-Estringana, P., Alonso-Blázquez, N., and Alegre, J.: Water storage capacity, stemflow and water funneling in Mediterranean shrubs, J. Hydrol., 389, 363–372, 2010.

Germer, S., Werther, L., and Elsenbeer, H.: Have we underestimated stemflow? Lessons from an open tropical rainforest, J. Hydrol., 395, 169–179, 2010.

Gordon, D. A. R., Coenders-Gerrits, M., Sellers, B. A., Sadeghi, S. M. M., and Van Stan II, J. T.: Rainfall interception and redistribution by a common North American understory and pasture forb, Eupatorium capillifolium (Lam. dogfennel), Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 24, 4587–4599, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-24-4587-2020, 2020.

Hanchi, A. and Rapp, M.: Stemflow determination in forest stands, Forest Ecol. Manag., 97, 231-235, 1997.

Honda, E. A., Mendonça, A. H., and Durigan, G.: Factors affecting the stemflow of trees in the Brazilian Cerrado, Ecohydrology, 8, 1351–1362, 2015.

Iida, S., Shimizu, T., Kabeya, N., Nobuhiro, T., Tamai, K., Shimizu, A., Ito, E., Ohnuki, Y., Abe, T., Tsuboyama, Y., Chann, S., and Keth, N.: Calibration of tipping-bucket flow meters and rain gauges to measure gross rainfall, throughfall, and stemflow applied to data from a Japanese temperate coniferous forest and a Cambodian tropical deciduous forest, Hydrol. Process., 26, 2445–2454, 2012.

Jia, X., Zha, T. S., Gong, J. N., Wang, B., Zhang, Y. Q., Wu, B., Qin, S. G., and Peltola, H.: Carbon and water exchange over a temperate semi-arid shrubland during three years of contrasting precipitation and soil moisture patterns, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 228, 120–129, 2016.

Jia, X. X., Shao, M. A., Wei, X. R., and Wang, Y. Q.: Hillslope scale temporal stability of soil water storage in diverse soil layers, J. Hydrol., 498, 254–264, 2013.

Jian, S. Q., Hu, C. H., Zhang, G. D., and Zhang, J. P.: Study on the throughfall, stemflow, and interception of two shrubs in the semiarid Loess region of China, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 279, 107713, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2019.107713, 2019.

Lacombe, G., Valentin, C., Sounyafong, P., de Rouw, A., Soulileuth, B., Silvera, N., Pierret, A., Sengtaheuanghoung, O., and Ribolzi, O.: Linking crop structure, throughfall, soil surface conditions, runoff and soil detachment: 10 land uses analyzed in Northern Laos, Sci. Total Environ., 616–617, 1330–1338, 2018.

Levia, D. F. and Frost, E. E.: A review and evaluation of stemflow literature in the hydrologic and biogeochemical cycles of forested and agricultural ecosystems, J. Hydrol., 274, 1–29, 2003.

Levia, D. F. and Germer, S.: A review of stemflow generation dynamics and stemflow-environment interactions in forests and shrublands, Rev. Geophys., 53, 673–714, 2015.

Levia, D. F. and Herwitz, S. R.: Interspecific variation of bark water storage capacity of three deciduous tree species in relation to stemflow yield and solute flux to forest soils, Catena, 64, 117–137, 2005.

Levia, D. F., Van Stan II, J. T., Mage, S. M., and Kelley-Hauske, P. W.: Temporal variability of stemflow volume in a beech-yellow poplar forest in relation to tree species and size, J. Hydrol., 380, 112–120, 2010.

Levia, D. F., Hudson, S. A., Llorens, P., and Nanko, K.: Throughfall drop size distributions: a review and prospectus for future research, WIREs Water, 4, e1225, https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1225, 2017.

Li, X., Xiao, Q. F., Niu, J. Z., Dymond, S., van Doorn, N. S., Yu, X. X., Xie, B. Y., Lv, X. Z., Zhang, K. B., and Li, J.: Process-based rainfall interception by small trees in Northern China: The effect of rainfall traits and crown structure characteristics, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 218–219, 65–73, 2016.

Liu, Y. X., Chang, Z. Y., and Gennady, P. Y.: Caragana (Fabaceae), in: Flora of China, edited by: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H., and Hong, D. Y., Science Press, Beijing and Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis, 528–545, http://www.iplant.cn/info/Caragana?t=foc (last access: 21 July 2022), 2010.

Llorens, P. and Domingo, F.: Rainfall partitioning by vegetation under Mediterranean conditions. A review of studies in Europe, J. Hydrol., 335, 37–54, 2007.

Magliano, P. N., Whitworth-Hulse, J. I., and Baldi, G.: Interception, throughfall and stemflow partition in drylands: Global synthesis and meta-analysis, J. Hydrol., 568, 638–645, 2019a.

Magliano, P. N., Whitworth-Hulse, J. I., Florio, E. L., Aguirre, E. C., and Blanco, L. J.: Interception loss, throughfall and stemflow by Larrea divaricata: The role of rainfall characteristics and plant morphological attributes, Ecol. Res., 34, 753–764, 2019b.

Martinez-Meza, E. and Whitford, W. G.: Stemflow, throughfall and channelization of stemflow by roots in three Chihuahuan desert shrubs, J. Arid Environ., 32, 271–287, 1996.

Molina, A. J., Llorens, P., Garcia-Estringana, P., Moreno de Las Heras, M., Cayuela, C., Gallart, F., and Latron, J.: Contributions of throughfall, forest and soil characteristics to near-surface soil water-content variability at the plot scale in a mountainous Mediterranean area, Sci. Total Environ., 647, 1421–1432, 2019.

Owens, M. K., Lyons, R. K., and Alejandro, C. L.: Rainfall partitioning within semiarid juniper communities: effects of event size and canopy cover, Hydrol. Process., 20, 3179–3189, 2006.

Pinos, J., Latron, J., Levia, D. F., and Llorens, P.: Drivers of the circumferential variation of stemflow inputs on the boles of Pinus sylvestris L. (Scots pine), Ecohydrology, 14, e2348, https://doi.org/10.1002/eco.2348, 2021.

Rivera, D. N. and Van Stan II, J. T.: Grand theft hydro? Stemflow interception and redirection by neighbouring Tradescantia ohiensis Raf. (spiderwort) plants, Ecohydrology, 13, e2239, https://doi.org/10.1002/eco.2239, 2020.

Sadeghi, S. M. M., Gordon, D. A., and Van Stan II, J. T.: A Global Synthesis of Throughfall and Stemflow Hydrometeorology, in: Precipitation Partitioning by Vegetation, edited by: Van Stan II, J. T., Gutmann, E., and Friesen, J., Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 49–70, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29702-2_4, 2020.

Soulsby, C., Braun, H., Sprenger, M., Weiler, M., and Tetzlaff, D.: Influence of forest and shrub canopies on precipitation partitioning and isotopic signatures, Hydrol. Process., 31, 4282–4296, 2017.

Spencer, S. A. and van Meerveld, H. J.: Double funnelling in a mature coastal British Columbia Forest: spatial patterns of stemflow after infiltration, Hydrol. Process., 30, 4185–4201, 2016.

Staelens, J., De Schrijver, A., Verheyen, K., and Verhoest, N.E.C.: Rainfall partitioning into throughfall, stemflow, and interception within a single beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) canopy: influence of foliation, rain event characteristics, and meteorology, Hydrol. Process., 22, 33–45, 2008.

Tonello, K. C., Rosa, A. G., Pereira, L. C., Matus, G. N., Guandique, M. E. G., and Navarrete, A. A.: Rainfall partitioning in the Cerrado and its influence on net rainfall nutrient fluxes, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 303, 108372, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2021.108372, 2021.

Van Stan II, J. T., Wagner, S., Guillemette, F., Whitetree, A., Lewis, J., Silva, L., and Stubbins, A.: Temporal dynamics in the concentration, flux, and optical properties of tree-derived dissolved organic matter in an epiphyte-laden oak-cedar forest, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 122, 2982–2997, 2017.

Van Stan II, J. T., Gutmann, E., and Friesen, J. (Eds.): Precipitation Partitioning by Vegetation – A Global Synthesis, Precipitation Partitioning by Vegetation, Springer Nature Switzerland, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29702-2, 2020.

Wang, X.-P., Wang, Z.-N., Berndtsson, R., Zhang, Y.-F., and Pan, Y.-X.: Desert shrub stemflow and its significance in soil moisture replenishment, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 15, 561–567, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-15-561-2011, 2011.

Wang, X. P., Zhang, Y. F., Hu, R., Pan, Y. X., and Berndtsson, R.: Canopy storage capacity of xerophytic shrubs in Northwestern China, J. Hydrol., 454, 152–159, 2012.

Whitworth-Hulse, J. I., Magliano, P. N., Zeballos, S. R., Gurvich, D. E., Spalazzi, F., and Kowaljow, E.: Advantages of rainfall partitioning by the global invader Ligustrum lucidum over the dominant native Lithraea molleoides in a dry forest, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 290, 108013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2020.108013, 2020a.

Whitworth-Hulse, J. I., Magliano, P. N., Zeballos, S. R., Aguiar, S., and Baldi, G.: Global patterns of rainfall partitioning by invasive woody plants, Global Ecol. Biogeogr., 30, 235–246, 2020b.

Xiao-Yan Li, Zhi-Peng Yang, Yue-Tan Li, and Henry Lin: Connecting ecohydrology and hydropedology in desert shrubs: stemflow as a source of preferential flow in soils, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 13, 1133–1144, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-13-1133-2009, 2009.

Xu, H. and Li, Y.: Water-use strategy of three central Asian desert shrubs and their responses to rain pulse events, Plant Soil, 285, 5–17, 2006.

Yang, X. L., Shao, M. A., and Wei, X. R.: Stemflow production differ significantly among tree and shrub species on the Chinese Loess Plateau, J. Hydrol., 568, 427–436, 2019.

Yuan, C., Gao, G. Y., and Fu, B. J.: Stemflow of a xerophytic shrub (Salix psammophila) in northern China: Implication for beneficial branch architecture to produce stemflow, J. Hydrol., 539, 577–588, 2016.

Yuan, C., Gao, G., and Fu, B.: Comparisons of stemflow and its bio-/abiotic influential factors between two xerophytic shrub species, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 1421–1438, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-1421-2017, 2017.

Yuan, C., Gao, G., Fu, B., He, D., Duan, X., and Wei, X.: Temporally dependent effects of rainfall characteristics on inter- and intra-event branch-scale stemflow variability in two xerophytic shrubs, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 23, 4077–4095, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-23-4077-2019, 2019.

Yue, K., De Frenne, P., Fornara, D. A., Van Meerbeek, K., Li, W., Peng, X., Ni, X., Peng, Y., Wu, F., Yang, Y., and Penuelas, J.: Global patterns and drivers of rainfall partitioning by trees and shrubs, Glob. Change Biol., 27, 3350–3357, 2021.

Zhang, H., Fu, C., Liao, A., Zhang, C., Liu, J., Wang, N., and He, B.: Exploring the stemflow dynamics and driving factors at both inter- and intra-event scales in a typical subtropical deciduous forest, Hydrol. Process., 35, e14091, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14091, 2021.

Zhang, Y., Li, X. Y., Li, W., Wu, X. C., Shi, F. Z., Fang, W. W., and Pei, T. T.: Modeling rainfall interception loss by two xerophytic shrubs in the Loess Plateau, Hydrol. Process., 31, 1926–1937, 2017.

Zhang, Y. F., Wang, X. P., Pan, Y. X., and Hu, R.: Variations of nutrients in gross rainfall, stemflow, and throughfall within revegetated desert ecosystems, Water Air Soil Pollut., 227, 183, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-016-2878-z, 2016.

Zhang, Y. F., Wang, X. P., Hu, R., and Pan, Y. X.: Meteorological influences on process-based spatial-temporal pattern of throughfall of a xerophytic shrub in arid lands of northern China, Sci. Total Environ., 619–620, 1003–1013, 2018.

Zhang, Y. F., Wang, X. P., Pan, Y. X., Hu, R., Chen, N., and Sandel, R. O.: Global quantitative synthesis of effects of biotic and abiotic factors on stemflow production in woody ecosystems, Global Ecol. Biogeogr., 30, 1713–1723, 2021.