the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Uncertainty, temporal variability, and influencing factors of empirical streamflow sensitivities

Sebastian Gnann

Bailey J. Anderson

Markus Weiler

The sensitivity of streamflow to changes in driving variables such as precipitation and potential evaporation is a key signature of catchment behaviour. Due to increasing interest in climate change impacts, streamflow sensitivities derived from observations have become a widely used metric for catchment characterization, model evaluation, and observation-constrained projections. However, there remain open questions regarding the robustness and temporal variability of empirically-derived sensitivities. In this paper, we revisit theoretical and empirical approaches to estimate streamflow sensitivities to precipitation and potential evaporation. First, we compare different estimation methods, primarily based on linear regression, using a synthetic dataset for which the sensitivities are known. Second, we extend this comparison and use two methods selected based on the previous analysis to estimate sensitivities for >1000 near-natural catchments. Third, we investigate how sensitivities change over time due to changes in the ratio between potential evaporation and precipitation (i.e., aridity index). Our results confirm that multiple regression is preferable to single regression, but that in presence of noise and correlation between precipitation and potential evaporation, even multiple regression methods can lead to high uncertainty, especially for potential evaporation. When analysing real catchments, sensitivity to precipitation is estimated consistently across methods, while sensitivity to potential evaporation is highly uncertain and often yields unrealistic values. Further, as the aridity index increases over time – a trend found in observational data – sensitivities decrease (by 15 %–70 % over 50 years) and can thus not be viewed as static. Empirical sensitivities, as well as their trends, relate strongly to the aridity index, but are also influenced by other factors, especially those related to catchment storage processes, as well as data uncertainty. Our results should urge caution in the use of empirical streamflow sensitivities for climate change impact assessments and call for further investigation.

- Article

(4595 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2381 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

In response to ongoing interest in climate change impacts, the sensitivity of streamflow to changes in climatic drivers has received considerable attention in recent years (e.g., Andréassian et al., 2016; Lehner et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023). In particular, sensitivities to precipitation, temperature, and potential evaporation are commonly used, though the concept can be extended to other driving variables that influence streamflow, such as storage (e.g., Berghuijs et al., 2016; de Lavenne et al., 2022; Weiler et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2023) or land cover changes (e.g., Anderson et al., 2022; Roderick and Farquhar, 2011; Steinschneider et al., 2013).

Sensitivity is defined as the change in streamflow per unit change in a certain driving variable. This can be expressed in absolute terms (e.g., by how many mm streamflow changes per mm change in precipitation) or in relative terms (e.g., by how many %-points streamflow changes per 1 % change in precipitation), the latter often being called elasticity (Andréassian et al., 2016; Sankarasubramanian et al., 2001). We will define both terms more formally later on.

One of the earliest studies explicitly mentioning the “sensitivity of water resource systems to climate variations” was by Němec and Schaake (1982), who used the Sacramento Soil Moisture Accounting model to estimate sensitivity of streamflow to changes in precipitation and potential evaporation for two contrasting basins (an arid and a humid one). This approach comprises one typical category of sensitivity studies, namely perturbation experiments using (process-based) simulation models of varying complexity (e.g., Němec and Schaake, 1982; Nijssen et al., 2001; Schaake, 1990). Another category are simple Budyko-type water balance models (Budyko, 1974), which provide analytical solutions describing the catchment water balance, typically at the climatological time scale. These models calculate streamflow and (complementary to this) actual evaporation as a function of precipitation, potential evaporation, and sometimes other factors (e.g., related to vegetation or land use), and can be used to obtain sensitivity estimates by taking partial derivates to the different driving variables (Andréassian et al., 2016; Dooge, 1992; Harman et al., 2011; Roderick and Farquhar, 2011; Sankarasubramanian et al., 2001). Lastly, empirical approaches have been used to derive sensitivities directly from observational data by means of data-based estimators or linear regression approaches (Andréassian et al., 2016; Chiew, 2006; Sankarasubramanian et al., 2001). Empirical approaches tend to invoke fewer assumptions and are observation-based, thus providing a benchmark for simple analytical models or complex process-based models. However, they are associated with uncertainty due to methodological choices and are influenced by the quality of the underlying observational data.

When studying streamflow sensitivity, it is important to consider the time scale under investigation. Many studies focus on long-term average fluxes (i.e., the climatological time scale), as this is of direct interest when studying how catchments respond to changes in climatic conditions. To empirically derive long-term sensitivities, it is common to aggregate time series of streamflow and its driving variables into annual values and then make use of year-to-year variability to approximate how catchments respond to long-term changes (Andréassian et al., 2016; Sankarasubramanian et al., 2001). Whether catchments actually respond to yearly changes in the same way as to long-term changes is, however, an assumption that may not always hold. As an alternative, it has been suggested to estimate sensitivities using multi-year averages (e.g., decadal averages; Zhang et al., 2022), though this requires long enough time series to be able to use non-overlapping blocks. In addition, it is worth noting that sensitivities can be assessed in many different ways – for example, by examining annual sensitivities in relation to sub-annual variations (e.g., warm and cold seasons; Ban et al., 2020), by considering different parts of the streamflow regime (e.g., multiple streamflow percentiles; Anderson et al., 2024), or by focusing on different time scales altogether (e.g., weekly sensitivities; Weiler et al., 2025).

Independent of how they are estimated, sensitivities (or elasticities) can be used in a variety of ways. They provide a model-derived summary metric describing how a hydrological system responds to change (Němec and Schaake, 1982; Schaake, 1990). They can be used for direct projections of climate change effects using simple sensitivity models (Roderick and Farquhar, 2011) or observation-based regression approaches (Zhang et al., 2023). They can be used for model evaluation (Wagener et al., 2022) and for constraining model ensembles (Lehner et al., 2019). And lastly, they generally serve as means for catchment characterization (Addor et al., 2018) and thus are frequently used in catchment classification studies (e.g., Almagro et al., 2024; Sawicz et al., 2011).

Due to their widespread use in the context of climate change impact research (e.g., Lehner et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023), it is important to have a clear understanding of both the concept of sensitivity and the methods used to estimate it. Recent studies often reported unrealistic (i.e., positive) values for empirically estimated sensitivities to potential evaporation (Andréassian et al., 2025b; Awasthi et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2020), as well as temporal variability in sensitivities and/or rainfall-streamflow relationships (Anderson et al., 2025; Fu et al., 2007; Matanó et al., 2025; Peterson et al., 2021; Saft et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2019). This warrants a closer look at existing methods used to empirically estimate sensitivities. The central aim of this paper is therefore to test the robustness of different empirical estimation methods and then to investigate potential temporal variability of sensitivities. To do so, we (1) test different approaches based on an analytical model for which the sensitivities are known, (2) apply two selected methods to a large sample of near-natural catchments, and (3) explore how empirical sensitivities change over time using long streamflow time series.

In the following, we first present formal definitions of streamflow sensitivity and elasticity (Sect. 2.1) and introduce the different empirical estimation methods tested in this paper (Sect. 2.2). These methods are then both applied to a synthetic dataset based on an analytical model (described in Sect. 2.3) and to observational data (data sources described in Sect. 3). Finally, we investigate how sensitivities change over time, both theoretically and using observational data (Sect. 2.4), and examine potential influencing factors that explain differences in empirical patterns compared to the analytical model (Sect. 2.5).

2.1 Definitions of sensitivity and elasticity

Sensitivity s is defined as the absolute change in streamflow ΔQ per absolute change in a certain driving variable, here precipitation ΔP and potential evaporation ΔEp. ΔQ indicates the deviations at each time step t (here usually years) from the long-term average ; for example, for streamflow we get . The Δ notation is used here due to our focus on empirical sensitivities. When studying sensitivities using analytical equations, this becomes the (partial) derivative ∂.

Elasticity e is closely related but focuses on percentage changes, so that both streamflow and its driving variables are normalised by their respective means , , and .

While both sensitivity and elasticity are dimensionless, they are often expressed in mm mm−1 or % %−1, respectively.

An interesting feature of elasticities is the hypothesis that there exists a so-called complementary relationship between eP and (which is embedded in Eq. 10 in Dooge, 1992, even though he did not explicitly mention that term). This complementary relationship states that the elasticities to P and Ep should sum up to 1, which was shown to be a characteristic of any Budyko-type equation where Q is solely determined by P and Ep (Zhou et al., 2015), but may not necessarily be true for real catchments.

2.2 Estimation methods of empirical sensitivities

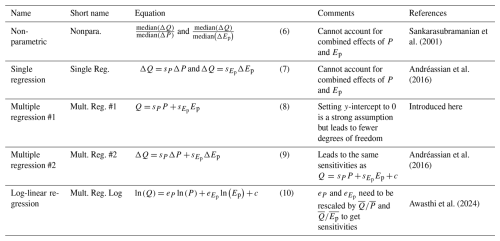

We test several methods to calculate sensitivities empirically, all listed in Table 1. In addition to the commonly used non-parametric method (Eq. 6; Sankarasubramanian et al., 2001), we use different regression-based methods (Andréassian et al., 2016). These include single linear regression using annual variations around the mean (Eq. 7), multiple linear regression using absolute annual values with y-intercept set to 0 (multiple regression #1; Eq. 8), multiple linear regression using annual variations around the mean with y-intercept set to 0 (multiple regression #2; Eq. 9), and log-linear regression (Eq. 10), which was recently proposed by Awasthi et al. (2024). We note that multiple regression #1 is not commonly used, but is included here as it yields interesting results (shown later). In addition to the regression coefficients, which represent the sensitivities, we also calculate R2 to check how much variance is explained by the different regression models and to investigate if the unexplained variance shows any patterns in relation to the sensitivity estimates, as well as p-values for each fitted parameter.

Table 1Methods used to empirically estimate streamflow sensitivity to precipitation and potential evaporation.

Besides deciding on the equation to fit (e.g., single or multiple regression), we need to decide on the fitting method when applying regression analysis (e.g., ordinary least squares or more advanced methods). Earlier studies found that the fitting method has little influence on sensitivity estimates (Andréassian et al., 2016). We also briefly tested different methods such as lasso or ridge regression (e.g., Dormann et al., 2013) and performed multiple regression sequentially (so-called stepwise partial regression), but found this to lead to virtually identical results. We thus do not further investigate the influence of the fitting method and also do not report any results here.

All methods are applied to annually averaged values. Since averaging of variables over more than a year has also been suggested (Andréassian et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2022), we briefly tested this approach on the observational dataset and estimated sensitivities using averages over non-overlapping 5-year blocks (see Fig. S1 in the Supplement). Since this method did not lead to any obvious improvements or additional insights, we do not further discuss it here.

2.3 Analytical model of streamflow sensitivity and synthetic dataset

The Turc–Mezentsev model is a Budyko-type model that takes long-term average precipitation P, potential evaporation Ep, and a shape parameter n as input, and returns streamflow Q (and, complementary to that, actual evaporation Ea). The parameter n is often set between 2 and 3 (see e.g., Lebecherel et al., 2013) and is assumed to relate to other factors influencing the catchment water balance, such as vegetation cover (e.g., Zhang et al., 2001). While the exact value of n is not of major importance here, we use a value of n=2.2, chosen to fit our observational dataset (described in Sect. 3) best by minimizing the average absolute error (see Fig. S3 in the Supplement).

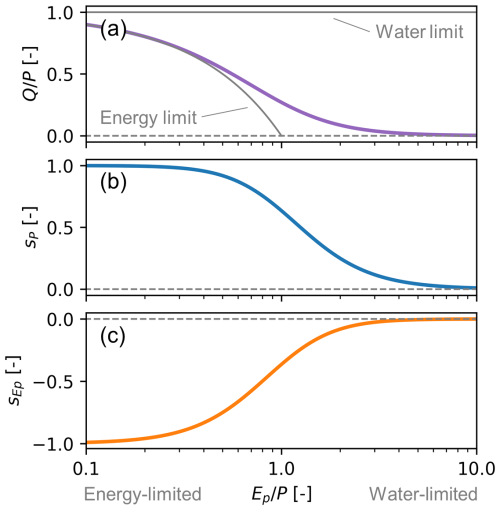

The Turc–Mezentsev model can also be used to analytically calculate the sensitivity of Q to P and Ep (which may be summarised to the aridity index ) by calculating partial derivates, so that we obtain a single sensitivity curve, which is a function of the aridity index. The resulting curves for (as a reference), sP, and are shown in Fig. 1.

Equation (11) is usually applied at long time scales, for which changes in storage are negligible (so that ). Accordingly, also the sensitivities (Eqs. 12 and 13) should be seen as sensitivities to long-term changes P and Ep. Here, we relax this assumption and use these equations to study year-to-year variability. We note that the same assumption is (implicitly) made in many sensitivity studies, which use year-to-year variability to estimate how catchments respond to long-term change, even though there is evidence that year-to-year variability in Q also responds to changes in, for instance, storage (Tang et al., 2020). For the theoretical analysis carried out here this does not matter, as we test how well different methods can estimate sensitivities from synthetically generated data with the assumption that storage changes are zero. It will, however, matter when interpreting sensitivity estimates based on observational data. Here, a mismatch in time scales (i.e., annual variations used to calculate empirical sensitivities vs. spatial variations of long-term water balances between catchments underlying the Turc–Mezentsev model) might lead to differences between the empirical and theoretical sensitivities.

Figure 1(a) Streamflow fraction of precipitation (), (b) streamflow sensitivity to precipitation sP, and (c) streamflow sensitivity to potential evaporation as a function of the aridity index (), all based on the Turc–Mezentsev model using n=2.2 (Eqs. 11–13). The grey lines in panel (a) indicate the water and energy limits, respectively. The energy limit poses a lower limit to streamflow, because not more precipitation can be lost to evaporation than potential evaporation. The water limit poses an upper limit to streamflow, because streamflow cannot exceed precipitation.

In addition, since the Turc–Mezentsev model is nonlinear, a linear regression might not match well the local derivative at the long-term mean, especially if year-to-year variability is large. To get an idea regarding how nonlinear the relationship could be for typical ranges of variability, we had a closer look at some example catchments, both synthetic ones and real ones (shown in Figs. S16 and S17 in the Supplement). The bivariate relationships between Q and P and Ep, respectively, appear to be mostly linear, though some weak nonlinearity can be seen especially for strongly water-limited catchments.

Based on the Turc–Mezentsev model, we create a synthetic dataset for which the actual sensitivities are known, which will serve as a baseline for the theoretical analysis that will follow. To do so, we first generate synthetic catchments with fixed long-term values of P and Ep that span a wide aridity gradient (both P and Ep range from 300 to 3000 mm yr−1). For each synthetic catchment, we then create 50 annual value pairs by sampling from a bivariate normal distribution with the standard deviations of P and Ep set to 15 % and 5 % of their means, respectively, and with a Pearson correlation ρP between P and Ep set to three different values: −0.5, 0, and +0.5. The standard deviations are chosen to be similar to the ones found in the observational dataset used (17 % for P and 4 % for Ep; data are described in Sect. 3). The correlation is added because P and Ep are regularly correlated in empirical data ( on average for the catchments used here; see Fig. S4 in the Supplement) and this is known to affect sensitivity estimates (e.g., Chiew et al., 2014). Note that we use Pearson correlation ρP for the generation of correlated data, but in all other cases we use the more robust Spearman rank correlation ρS to quantify the strength of variable associations. Having created synthetic P and Ep data, we use the Turc–Mezentsev model to calculate Q for each annual pair of P and Ep (Eq. 11) as well as the sensitivities corresponding to the long-term values of P and Ep (Eqs. 12 and 13).

In addition, we investigate the influence of data uncertainty, which affects every hydrological variable (McMillan et al., 2012, 2018). To do so, we added normally distributed noise to P, Ep, and Q (after they have been generated). We use 2.5 % of each variable's mean as standard deviation, so that about 95 % of the data will fall within ±5 % of the mean (±2 times the standard deviation). While observational uncertainty is often estimated to be around 10 % or higher, especially for precipitation (McMillan et al., 2012, 2018), these values are not directly comparable, as data uncertainty is often systematic (e.g., due to precipitation undercatch) and might be partly averaged out when using annual sums. Since the main aim here is to investigate the potential impact of data uncertainty, we decided to use a standard deviation of 2.5 %, bearing in mind that the actual impact may vary depending on the actual uncertainty of the different variables.

Overall, we obtain 6 synthetic scenarios: three different strengths of correlation, each without and with random noise. The different sensitivity estimation methods (Table 1) are then used to derive sensitivities sest, which are compared to the actual sensitivities sact (Eqs. 12 and 13). This is done both visually and by quantifying the relative error as [%], which is then averaged across all samples by taking the arithmetic mean.

2.4 Temporal analysis

As can be seen from Eqs. (12) and (13), the streamflow sensitivities themselves depend on the aridity index, so that (at least theoretically) a change in aridity will lead to a change in the sensitivities. We can therefore also use the analytical model to investigate how typical temporal trends found for P and Ep translate into trends in sensitivities (or elasticities) and compare these theoretically calculated trends with empirically estimated ones. To do so, we first average P, Ep, and Q from the observational datasets (described in Sect. 3) over 20-year moving blocks in a longer time series (at least 50 years), resulting in at least 30 blocks. We then calculate both theoretical sensitivities and streamflow values (using the Turc–Mezentsev model forced with P and Ep) and empirical sensitivities (using multiple regression on P, Ep, and Q) for each 20-year block. Finally, we calculate trends of theoretical and empirical sensitivities over time with the Theil-Sen trend slope estimator (Sen, 1968). In order to calculate relative trends (in %), we normalize the trends by the sensitivities calculated in the first 20-year block (i.e., at the beginning of the time series). The trend analysis is carried out separately for different subsets of observational data (described in Sect. 3), for which we use an independently calibrated an n-value each to ensure that the Turc–Mezentsev captures regional conditions reasonably well.

2.5 Calculation of additional catchment indices

To aid catchment selection and the interpretation of the results, we calculate three further indices per catchment: a precipitation seasonality index (PS), the fraction of precipitation falling as snow (fS), and a baseflow index (BFI). The seasonality index quantifies the seasonal timing of precipitation relative to temperature (Woods, 2009), indicating whether most precipitation falls in summer (PS>0) or in winter (PS<0). The fraction of precipitation falling as snow is calculated by dividing the sum of precipitation falling on days with temperatures T below 0 °C by the total precipitation sum, and it ranges from 0 to 1. The baseflow index is a measure of how flashy or smooth a streamflow hydrograph is, often linked to groundwater contributions to streamflow. The baseflow index is calculated by dividing baseflow estimated using a digital filter (Institute of Hydrology, 1980) by total streamflow, and it ranges from 0 to 1.

In addition to synthetic data, we also test different sensitivity estimation methods using observational data. We use data from four large sample datasets (CAMELS-US, CAMELS-GB, CAMELS-AUS v2, CAMELS-DE) and select catchments based on the following criteria: we only keep time series with less than 5 % missing values, at least 30 years in length, a fraction of precipitation falling as snow fS<0.2, and where Q does not exceed P. All the time series are aggregated to annual values based on the water year. For the trend analysis, we focus on CAMELS-AUS and CAMELS-DE due to availability of long time series and only kept catchments with at least 50 years of data. The Australian dataset is further divided into two subsets, one where most precipitation falls in winter (PS<0) and one where most precipitation falls in summer (PS>0), to study trends across regions that are climatologically not too different. Details and references are reported in Table 2.

We always use national forcing products to ensure high quality data, as global products were reported to be associated with substantial uncertainties for CAMELS-US and CAMELS-GB (Clerc-Schwarzenbach et al., 2024), and as we assume that national datasets reflect regional conditions best. This come at the cost of potentially reducing comparability, though, especially regarding Ep, which is estimated using different equations (see Table 2). We therefore made a brief comparison to study the influence of different P and Ep datasets on the resulting sensitivities for CAMELS-AUS and CAMELS-DE, the two datasets used for the trend analysis. In particular, we estimated the sensitivities using P and Ep from national data sources (our default option here; see Table 2) and from their Caravan extension (Kratzert et al., 2023), which is based on ERA5-land and uses the Penman–Monteith equation in its updated version to calculate Ep (Kratzert et al., 2025).

Overall, the estimated sensitivities are similar (see also Fig. S2 in the Supplement). For CAMELS-AUS v2, we obtain a Spearman rank correlation of ρS=0.97 and a mean absolute error of MAE = 0.09 for streamflow sensitivity to precipitation, and ρS=0.94 and MAE = 0.07 for streamflow sensitivity to potential evaporation. For CAMELS-DE, we obtain ρS=0.94 and MAE = 0.08 for streamflow sensitivity to precipitation, and ρS=0.86 and MAE = 0.09 for streamflow sensitivity to potential evaporation. In conclusion, we find that the resulting sensitivities somewhat depend on the forcing products used, but that the differences are rather small and also do not substantially alter the trend analysis (not shown here). We will come back to the issue of reliably estimating Ep in the discussion, but note that this is not our main focus here.

4.1 Comparison of sensitivity estimation methods using the analytical model

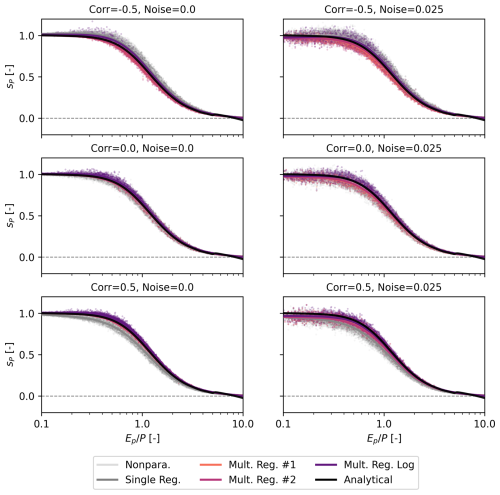

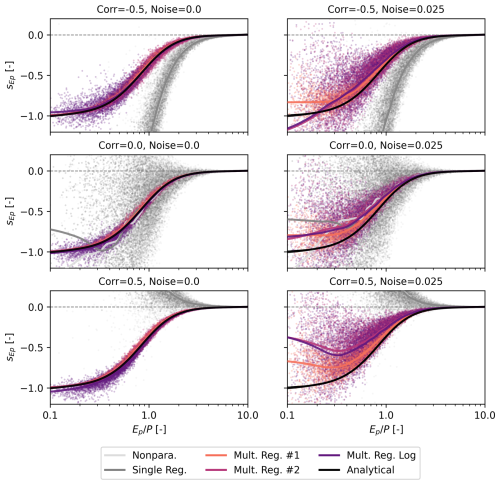

The analytical Turc–Mezentsev model allows us to test the different sensitivity estimation methods (Table 1) and compare them to theoretical values, thereby illustrating how the methods perform under known conditions. Figures 2 and 3 show the resulting sensitivity estimates for all methods as a function of the aridity index. Table 3 lists the relative errors, which are also visualised as bar plot in Fig. S5 in the Supplement.

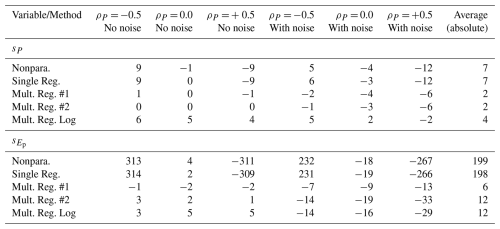

Table 3Relative errors erel [%], rounded to full percentages, and absolute average of the relative errors for the different estimation methods. Figure S5 in Supplement also shows the values as bar plots.

Figure 2Streamflow sensitivity to precipitation as a function of the aridity index. Theoretical values are based on the Turc–Mezentsev model (n=2.2), forced with precipitation and potential evaporation values that exhibit different degrees of correlation and noise to simulate real observations. The estimates resulting from the different methods are shown as point clouds with a LOESS regression (the fraction of data points which influence the smoothing at each value is set to 0.1) to aid visualization.

Figure 3Streamflow sensitivity to potential evaporation as a function of the aridity index. Theoretical values are based on the Turc–Mezentsev model (n=2.2), forced with precipitation and potential evaporation values that exhibit different degrees of correlation and noise to simulate real observations. The estimates resulting from the different methods are shown as point clouds with a LOESS regression (the fraction of data points which influence the smoothing at each value is set to 0.1) to aid visualization.

Overall, the estimation of streamflow sensitivities to potential evaporation results in much larger relative errors than for sensitivities to precipitationsP. The smallest relative errors are obtained in absence of noise and with no correlation between P and Ep (erel from −2 % to 5 %). In presence of noise, the performance degrades for most methods, especially for . For sP, multiple regression methods #1 and #2 lead to the lowest relative errors overall (average absolute erel=2 %), followed by log-regression (4 %). For , multiple regression method #1 leads to the lowest relative error overall (average absolute erel=6 %), followed by method #2 and log-regression (both 12 %).

When P and Ep are correlated, the nonparametric method and single regression (i.e., methods that do not account for both P and Ep) lead to large and systematic errors. For instance, with negative correlations of −0.5, streamflow sensitivities to precipitation (erel from 6 to 10 %) and to potential evaporation (erel from 231 % to 314 %) are – on average – systematically overestimated (Table 3). By contrast, when correlations are set to +0.5, sP (erel from −12 % to −10 %) and (erel from −311 to −266 %) are systematically underestimated. For multivariate methods, the relative errors are much smaller, but we still find systematic errors, especially for and in presence of noise. For instance, with negative correlations of −0.5 and with noise, method #1 underestimates by −7 %, while method #2 and log-regression both underestimate it by −14 % (see also Fig. 3). Yet even when P and Ep are not correlated, we find systematic underestimation of (erel from −9 % to −19 %).

4.2 Comparison of sensitivity estimation methods using observational data

Since the Turc–Mezentsev model is a very simplified representation of reality, methods that perform well compared to the theoretical values may not perform well based on observational data that are influenced by more than just P and Ep (e.g., storage changes from year to year) and that are subject to other types of uncertainty (e.g., systematic bias). Hence, we now apply two selected methods to a large sample of near-natural catchments. We decided to focus only on methods #1 and #2, since log-regression leads to very similar results as method #2 and all univariate methods lead to poor performance if P and Ep are correlated (see Figs. 2 and 3). This is indeed the case for most catchments, with Pearson correlation ρP between P and Ep in the observational data being mostly negative and averaging −0.42.

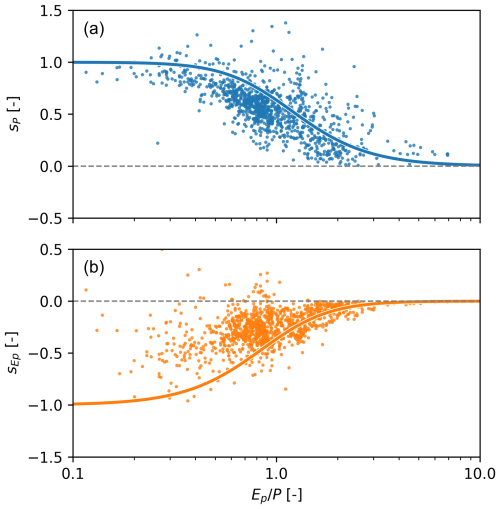

When applying methods #1 and #2 to observational data, we find good agreement between the two methods for sP (Spearman rank correlation ρS=0.96) and little agreement for (ρS=0.07), shown in Fig. 4. Theoretically, we would expect sP to range from 0 to 1 and to range from −1 to 0. That is, should always be negative, as an increase in evaporative demand should be related to a decrease in streamflow. However, we find that 52 % of values for are positive when using method #2, while it is only 3 % when using method #1. In terms of explained variance by the multiple regression methods, the two methods perform similarly. The overall median R2 is 0.65 for #1 and 0.68 for #2, indicating an acceptable fit but also substantial variation left unexplained. The p-values, shown in Fig. S10 in the Supplement, are almost always larger than 0.05 for sP (in more than 99 % of the catchments). The p-values for vary, with values being smaller than 0.05 in 83 % of the catchments for method #1 and only in 16 % of the catchments for method #2.

Figure 4Comparison of streamflow sensitivity to (a) precipitation (ρS=0.96) and (b) potential evaporation (ρS=0.07) calculated using multiple regression methods #1 and #2 with observations from 1121 catchments. The grey dashed line shows the 1:1 line.

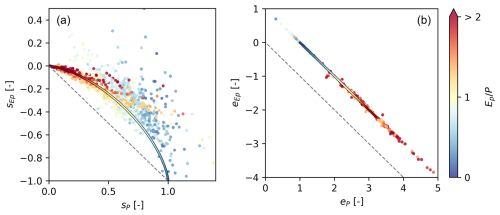

Since there is little difference for sP and method #1 provides the most realistic values for , the following analyses are based on method #1. We also added all figures using method #2 to the Supporting Information. We first compare the empirically estimated sensitivities to the Turc–Mezentsev model, shown in Fig. 5. Overall, both sP and follow the theoretical pattern and decrease with increasing aridity (the results are similar for elasticities; see Fig. S6 in the Supplement).

Figure 5Streamflow sensitivity to (a) precipitation and (b) potential evaporation, calculated using multiple regression #1 with observations from 1121 catchments. Both panels show empirically calculated values (dots) and theoretical values based on the Turc–Mezentsev model with n=2.2 (solid lines). Note that the y-axes are capped for better visibility and that two catchments plot above 0.5 for .

The fact that the sensitivities estimated empirically using year-to-year variability show a similar pattern as the sensitivities obtained by calculating partial derivates of a spatial relationship (Eqs. 12 and 13) hints at some degree of space-time-symmetry. However, the theoretical values tend to be underestimated and there is substantial variability, clearly more than for a Budyko-type plot of the same catchments (shown in Fig. S3 in the Supplement). The R2 values tend to be smaller for catchments further away from the theoretical Turc–Mezentsev curves (using n=2.2), with ρS between R2 and the relative deviation of the empirical sensitivities from the Turc–Mezentsev curve being 0.60 for sP and 0.25 for (see Fig. S11 in the Supplement). This suggests that other predictors not included in the regression model matter, too.

We briefly considered several other factors commonly hypothesised to influence annual Q variability apart from P and Ep, namely storage, seasonality, and snow, here approximated with BFI, PS, and fS, respectively. In particular, we tested if the differences between the Turc–Mezentsev-based sensitivities (i.e., the curves shown in Fig. 5) and the empirical sensitivities are related to any of these variables (see also Figs. S12–S14 in the Supplement). We found the strongest correlation between the relative deviation from the Turc–Mezentsev curve and BFI ( for sP and −0.44 for ), followed by fS (−0.31 and −0.46), and PS (0.09 and 0.20).

Another way to visualise the resulting sensitivities is to plot sP and against each other, which is shown in Fig. 6 with each catchment coloured according to its aridity index. We can see that the Turc–Mezentsev model leads to a single curve, meaning that each sP is associated with a unique , both being a function of the aridity index (cf. Eqs. 12 and 13). The same holds true for elasticities eP and , which plot as a straight line that follows the so-called complementary relationship (). The empirical patterns roughly follow the analytical ones in the case of sensitivities, and almost show a perfect match for elasticities. Note, though, that this refers to the overall pattern and not individual catchments, which may sit on the theoretical line but at the wrong location with respect to their aridity index.

Figure 6(a) Streamflow sensitivity to precipitation plotted against streamflow sensitivity to potential evaporation. (b) Streamflow elasticity to precipitation plotted against streamflow elasticity to potential evaporation. Both panels show empirically calculated values using multiple regression #1 (dots in the back) and theoretical values based on the Turc–Mezentsev model (line in front), coloured according to the aridity index. The grey dashed line starts at the origin and has a slope of −1, so that values plotting above it imply that (a) and (b).

4.3 Change of sensitivities over time

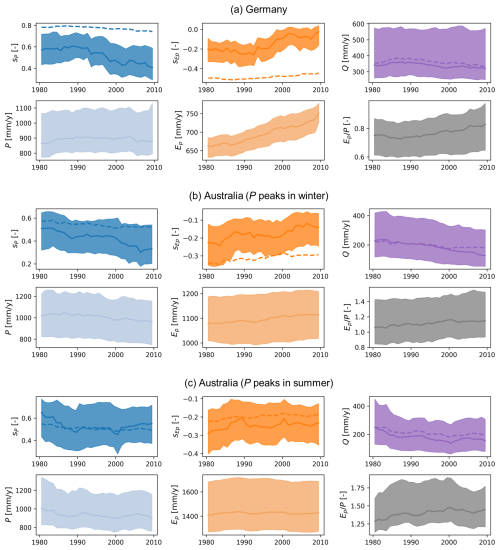

The strong relationship between streamflow sensitivity and aridity index found when comparing many catchments (Fig. 5; Andréassian et al., 2025a; Sankarasubramanian et al., 2001) suggests that a change in aridity index over time will also lead to changes in sensitivities for individual catchments. Theoretically, the Turc–Mezentsev model predicts a decrease (in absolute terms) in both sensitivities as aridity increases. Using sufficiently long observational records, we can calculate actual trends using sensitivity estimates over different time blocks (here based on method #1) and compare them to theoretical trends (via Eqs. 12 and 13) based on observed changes in precipitation and potential evaporation (and thus aridity index). This is done separately for Germany and two Australian subsets, which were split according to whether most precipitation falls in winter or in summer. The resulting trends are shown in Figs. 7 and quantified in Table S1 in the Supplement. We find an increase in the aridity index over time, especially in Germany. Accordingly, the sensitivities decrease (in absolute terms) over time in all cases. However, the trend magnitudes are overall stronger in observational data (between 15 % and 70 % decrease) than in the analytical model (between 5 % and 26 % decrease). In Germany, we generally find lower sensitivities than based on the Turc–Mezentsev model, but the trends in the observational data are larger (26 % vs. 5 % for sP and 70 % vs. 11 % for ), see Fig. 7a. In the Australian subset where most precipitation falls in winter, we find a somewhat similar pattern, with larger trends in the observational data than in the model (40 % vs. 18 % for sP and 49 % vs. 26 % for ), see Fig. 7b. In the Australian subset where most precipitation falls in summer, both the sensitivities and the trends are relatively close to the analytical model (15 % vs. 8 % for sP and 15 % vs. 15 % for ), see Fig. 7c.

Figure 7Change of streamflow sensitivities and other variables over time for (a) 144 catchments in Germany, (b) 100 catchments in Australia with most precipitation falling in winter (PS<0), and (c) 109 catchments in Australia with most precipitation falling in summer (PS>0). Shaded areas indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles and thick lines indicate the median of all catchments. Dashed lines indicate the trends calculated with the Turc–Mezentsev model for the sensitivities and Q based on observed P and Ep data and using a calibrated value of n=1.9 for (a), n=1.7 for (b) and n=2.6 for (c). Sensitivities are calculated using method #1 over 20-year blocks with the middle year shown (e.g., 1980 indicates a block from 1970 to 1990).

In absolute terms, most of the observed trends are in the order of around 0.15, meaning that at the end of the 50-year period a catchment that originally experienced a decrease of 0.5 mm in Q per mm decrease in P would now experience a decrease of only 0.35 mm in Q per mm decrease in P. Conversely, an increase in Ep at the end of the time period would lead to a smaller absolute reduction in Q, even though Ep related trends are likely less reliable given the uncertainty discussed previously.

5.1 Comparison of sensitivity estimation methods using an analytical model

Overall, univariate methods are unreliable in presence of correlation between P and Ep, which is the case for most catchments studied here (average ). While the limitation of univariate methods has been reported before (e.g., Andréassian et al., 2016), our results explicitly link errors in univariate methods to the correlation between P and Ep. The nonparametric method and single regression are therefore unreliable sensitivity estimators in most cases, especially for of . In addition, even multivariate methods show systematic deviations from the analytical curves. While the multivariate methods always lead to an underestimation of (i.e., less negative values) in presence of noise, the curves shown in Fig. 3 still tend to be more negative on average for and more positive on average for , which is the same general pattern as for the univariate methods. It is sometimes argued that multiple regression accounts for the correlation between predictors, yet this statement may be a bit misleading. Multiple regression estimates the effect of one predictor while holding the others constant, but strong correlations between predictors (multicollinearity) can inflate standard errors and produce poorly conditioned coefficients that are highly sensitive to small changes in the data (Dormann et al., 2013). In presence of strong correlations (e.g., when wet years are typically associated with reduced potential evaporation), there is little variation in one predictor that does not overlap with the other, making it difficult to estimate unique effects.

Multivariate methods perform relatively reliable for sP (2 %–5 % relative error on average), but they are less reliable for (6 %–12 % relative error on average). The absolute values of are always smaller than for sP for a given aridity index (see e.g., Fig. 7a, where all theoretical values plot above the dashed line) and so is their year-to-year variability (standard deviation was set to 15 % for P and 5 % for Ep), which could explain why is generally more difficult to estimate. This is substantiated by two additional checks (not shown here): if we increase the noise (smaller signal-to-noise ratio), the relative errors for both sP and increase; and if we increase the year-to-year variability of Ep in comparison to P, the relative errors for sP and become higher and lower, respectively.

Overall, the general underestimation (in absolute terms) of in presence of noise might thus largely be due to relatively little variation in Ep compared to P and to noise (cf. regression dilution), with additional bias due to correlation between P and Ep. While there are other regression methods that could be tested, our results suggest that the problem lies not primarily in the fitting method, but rather in general limitations of using (multiple) regression to estimate sensitivities from noisy and correlated data. In summary, despite the simplicity of our synthetic experiment, it illustrates that none of the methods can reliably estimate the sensitivities in all cases. This suggests similar or larger uncertainties for observational data, where additional factors may complicate the estimation of sensitivities, such as systematic biases (e.g., due to precipitation undercatch) or water balance issues (e.g., due to inter-catchment groundwater flow). This could also be studied using a synthetic experiment, but is beyond the scope of this paper.

5.2 Comparison of sensitivity estimation methods using observational data

5.2.1 Uncertainty in empirical sensitivity estimates

Overall, multiple regression methods #1 and #2 lead to similar values for sP, but show large disagreement for . This generally agrees with the results using the analytical model, which also showed larger disagreement for . As discussed in Sect. 5.1, absolute values of are always smaller than for sP, and previous studies also reported that changes in precipitation dominate the streamflow response of catchments (Berghuijs et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2023). In addition, year-to-year variability in Ep (standard deviation of 4 % on average) tends to be smaller than for P (17 %), so that the already smaller might be more difficult to constrain empirically, since the signal-to-noise ratio is relatively low (cf. Chiew et al., 2014). Alternative options which may help to constrain sensitivity values through regionalisation are pooled regression methods (e.g., panel regression; Anderson et al., 2025; Awasthi et al., 2024). This may allow robust estimation at the regional scale, although at the expense of unreliable sensitivity estimates at individual locations.

More than half of the values based on method #2 are larger than zero, which would suggest an increase in streamflow with increasing Ep. This cannot be generally attributed to concurrent increases in P, because P and Ep are anti-correlated. A considerable fraction of positive or zero values for sensitivities (or elasticities) to potential evaporation or temperature was also reported in other papers (Anderson et al., 2022; Andréassian et al., 2016, 2025b; Awasthi et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023). While this may be perceivable in certain circumstances (e.g., when warmer years are associated with increased precipitation intensity, or due to melt water contributions) it is unrealistic for this to occur in more than half of all catchments, casting doubt on the reliability of these sensitivity estimates. Alternatively, if these sensitivities were to capture actual catchment behaviour, it would imply that both simple Budyko-type and more complex simulation models, which usually show negative sensitivities to Ep (e.g., Roderick and Farquhar, 2011; Xiao et al., 2020), omit or misrepresent crucial processes related to evaporation. While method #1 leads to values of that mostly fall between −1 and 0, these values are often relatively small compared to the Turc–Mezentsev model. This might partly be a consequence of the method, which showed systematic underestimation in the synthetic experiment (Fig. 3). Hence, these estimates should also be interpreted with caution.

5.2.2 Patterns in empirical streamflow sensitivities and influence of catchment storage processes

Comparing observation-based sensitivities to the Turc–Mezentsev model, we find that both sP and tend to be lower in observational data. Since Turc–Mezentsev is a climate-only model, actual sensitivities to climate (P and Ep) are lower in real catchments where other factors matter, too. Besides data uncertainty, these include storage processes, seasonality, snow, vegetation characteristics, or inter-catchment groundwater flow (e.g., Andréassian et al., 2025b; Weiler et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2023). It is also likely that in less strictly filtered catchment datasets (see Sect. 2.5), the scatter will be larger due to other influences, such as human interventions in the water cycle. Still, especially sP follows the theoretical pattern relatively well, substantiating the strong influence of the aridity index on streamflow sensitivities.

The catchments that fall further away from the Turc–Mezentsev curves tend to have lower R2 and correlate substantially with the BFI and the snow fraction, and only weakly with precipitation seasonality. This can only be viewed as a very preliminary analysis, because other (more difficult to calculate) factors could have also been tested and because these different factors are not completely independent of each other. Still, they suggest that catchments with high BFI and large snow fractions tend to have lower sensitivities, possibly because these processes buffer year-to-year variability in precipitation and potential evaporation. While precipitation seasonality was shown to influence streamflow sensitivities in other studies (Andréassian et al., 2025b; Sankarasubramanian et al., 2001), this effect was less clearly pronounced here.

Though our main focus here is not to investigate in detail additional influences on sensitivities, we also fitted a regression model that includes a storage term, here approximated by the average streamflow from the previous year (see Fig. S15 in the Supplement). This led to two main insights. First, the median R2 increased from 0.65 to 0.69, suggesting that the storage term adds some, but not much, explained variance. Second, sP and stayed almost the same, indicating that the storage term only explains additional variance not captured by the other sensitivities, and does not change their values. While additional variables can therefore be included in the sensitivity calculation, it is worth noting that (unlike here) this could lead to changes in the sensitivity estimates. If the sensitivities depend on the regression model fitted, interpretation of the resulting regression coefficients becomes more challenging. Also, regression models with many predictors increase the risk of overfitting (e.g., to certain combinations of catchments with specific correlation structures), especially when predictors are correlated or the signal-to-noise ratio is low. Thus, while including additional variables may increase our understanding of the drivers of (annual) streamflow variations (e.g., Andréassian et al., 2025b), it also necessitates a close look at the meaning and robustness of the resulting sensitivity estimates.

5.2.3 The complementary relationship

Interestingly, method #1 appears to enforce the so-called complementary relationship (Awasthi et al., 2024; Dooge, 1992; Zhou et al., 2015). This might be due to the nature of the equation used. If we reformulate Eq. (8) and substitute the sensitivities with elasticities, we get:

If we assume that the fluctuations are much smaller than the means, the means cancel out and we get: .

While the complementary relationship should hold if catchments follow Budyko-type behaviour (i.e., Q is solely controlled by variability in P and Ep), real catchments do not necessarily behave that way. As soon as other factors (e.g., storage, changes in vegetation, human impacts) strongly affect a catchment's water balance and/or its sensitivity, we should not expect the relationship to hold. It is worth noting that the complementary relationship may be extended to account for elasticities to any number of driving variables (cf. Zhou et al., 2015). Yet, this should only be valid if all (major) drivers of streamflow variability are accounted for and in absence of large uncertainties. Overall, the so-called complementary relationship can thus be used to constrain sensitivity estimates, but also invokes assumptions that should be stated and assessed.

5.2.4 Other uncertainties and limitations

There are various sources of uncertainty when working with observational data, which will affect empirically estimated sensitivities. Besides measurement uncertainty, catchment averages of P and Ep rely on spatial interpolation procedures that introduce uncertainty (McMillan et al., 2012, 2018). These uncertainties are typically not purely random and may affect empirically estimated sensitivities in systematic ways. For instance, systematic underestimation of P (especially its variability) will lead to lower sensitivities. But even random uncertainties can affect sensitivity estimated based on linear regression, since large uncertainties compared to natural variability (i.e., a low signal-to-noise ratio) will impact the accuracy of regression coefficients, as shown in the synthetic experiment.

To minimise uncertainties arising from observational data, we selected catchments that are relatively unimpacted and come with long, mostly complete time series. We also only used national forcing products, since they are usually less uncertain than global products (Clerc-Schwarzenbach et al., 2024). In the case of the German catchments, for instance, the Hargreaves Ep estimates contained in CAMELS-DE differ substantially from Penman–Monteith Ep estimates (ρS=0.38) contained in Caravan, even though this difference does not substantially affect the resulting sensitivities (see Fig. S2). The data comparison here was rather brief, however, and a more extensive comparison of different Ep estimates might provide additional insights. More generally, since Ep is not a measurable but a modelled quantity, it is also associated with substantial conceptual uncertainty. One alternative option would be the use of net radiation (normalised by latent heat of vaporisation) directly to avoid the use of a model for estimating potential evaporation, which may become even more uncertain when looking at climate projections (cf. Milly and Dunne, 2016).

5.3 Change of sensitivities over time

When investigating long time spans (50 years), we find that – in accordance with the analytical model – the sensitivities decrease as aridity increases. This finding is mirrored in results previously reported for elasticities in the US (Anderson et al., 2025), though the trends there were less clearly expressed, differed between regions, and were not explicitly related to trends in aridity. While not directly comparable, the relative trends estimated here (between 15 % and 70 % decrease) are in a similar range as the relative variations in interannual elasticity compared to long-term elasticity estimates (between 4 % and 48 %) found by Anderson et al. (2025), which also showed lower elasticity in hot and dry years. This suggests that temporal changes in sensitivities of that order of magnitude are a more widespread phenomenon. Overall, both sP and decrease substantially over the 50 years investigated, suggesting that sensitivities may not be robust metrics for mid- to long-term projections. This holds true even without considering other factors that might influence the water balance in a future with elevated CO2 concentrations (e.g., interactions between P and Ep, or changes in stomatal conductance).

Especially for the German catchments and the Australian subset where most precipitation falls in winter (Fig. 7), the theoretical and empirical trends show large differences. For both subsets, we find that the decreasing trend is larger than predicted by the analytical model and that the sensitivities themselves are lower than the Turc–Mezentsev estimates. It is unlikely that these differences are solely due to data uncertainty, because they generally remain when different data sources are used. Rather, the results suggest that these catchments (or at least their year-to-year variations) are less driven by annual totals of precipitation and potential evaporation, for instance due to larger influence of catchment storage, precipitation seasonality, or changes in land cover and human impacts. Interestingly, the average trend in streamflow is roughly captured by Turc–Mezentsev model calibrated to each subset, but the sensitivities are not (see Fig. 7). This substantiates that year-to-year variability is, in many catchments, not necessarily a good proxy for responses to longer term climatic changes.

The influence of precipitation seasonality is not conclusive, as the pattern found for the German catchments where most precipitation falls in summer is more similar to the pattern found for the Australian subset where most precipitation falls in winter. Yet the German catchments and the Australian subset with winter dominant precipitation both have relatively high BFI values on average, much higher than the Australian subset with summer dominant precipitation (see Fig. S18). In line with the previous finding that catchments with high BFI have lower sensitivities, the same catchments might also respond less directly to climatic trends, for instance due to slower groundwater responses. Finally, while we fitted the n-value to each subset for the trend analysis, using a fixed value might also explain some of the difference between analytical and empirical trends, as it has been shown that n might change as a consequence of vegetation adapting to new conditions (Nijzink and Schymanski, 2022). These present just some hypotheses that might explain (parts of) the trends, but that require more extensive testing.

A systematic comparison of empirical, primarily regression-based, methods for estimating streamflow sensitivities to precipitation and potential evaporation indicates that streamflow sensitivity estimates are often highly uncertain, especially for potential evaporation. This applies both to a synthetic experiment using an analytical model (Turc–Mezentsev) and to observations from >1000 near-natural catchments, and can also be transferred to streamflow elasticities. While multivariate regression methods are preferable over univariate methods, the commonly employed multiple regression approach resulted in unrealistic streamflow sensitivities to potential evaporation for the majority of catchments studied here. Using a variant of multiple regression (with an intercept of zero) resulted in the lowest relative errors in the synthetic experiment and leads to fewer unrealistic values when applied to observational data, likely because it enforces the complementary relationship (which states that elasticities to P and Ep should sum up to 1). This method, however, invokes strong assumptions and may still underestimate (or poorly estimate) sensitivities to potential evaporation, and should therefore not be regarded as a definite recommendation. One possible reason for the difficulty in estimating sensitivity to potential evaporation is the low year-to-year variability in potential evaporation compared to precipitation and compared to observational uncertainty. Using unrealistic estimates of sensitivities to potential evaporation may be particularly problematic in regions where climate change impacts are largely driven by changes (typically increases) in evaporative demand and not precipitation totals, as is the case for Germany. In such instances, sensitivity-based projections may be deemed unreliable even if sensitivity to precipitation is accurately estimated. In addition, both theoretical and empirical results show that sensitivities decrease over time as aridity increases, indicating that static sensitivities may be unreliable for projections of climate change impacts. Lastly, while the sensitivities are strongly related to the aridity index, we found evidence that catchments with larger influence of storage processes (e.g., groundwater, snow) show lower sensitivities to climate variables but also stronger trends than predicted by the analytical model. Overall, our results should urge caution in the use of empirical sensitivities for both short-term and long-term projections and highlight the need for further investigation.

CAMELS-US v1.2 is available at https://doi.org/10.5065/D6MW2F4D (Newman et al., 2022). CAMELS-GB is available at https://doi.org/10.5285/8344e4f3-d2ea-44f5-8afa-86d2987543a9 (Coxon et al., 2020b). CAMELS-AUS v2 is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14289037 (Fowler et al., 2024). CAMELS-DE is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13837553 (Dolich et al., 2024). Caravan is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7944025 (Kratzert et al., 2025). Python code to reproduce the results and figures can be accessed at https://github.com/SebastianGnann/Streamflow_sensitivities (last access: 28 January 2026) and is permanently archived at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18302902 (Gnann, 2026). Code development was aided by Perplexity and GitHub Copilot.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-30-779-2026-supplement.

SG conceived the study, refined it based on discussions with all co-authors, and performed all analyses. SG prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank Felix Radtke for providing insights on streamflow elasticities in Germany and Carsten Dormann for advice on multiple regression methods. We also thank the two reviewers for the constructive comments that helped to improve our manuscript and the editor for handling our manuscript.

This open-access publication was funded by the University of Freiburg.

This paper was edited by Rohini Kumar and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Addor, N., Newman, A. J., Mizukami, N., and Clark, M. P.: The CAMELS data set: catchment attributes and meteorology for large-sample studies, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 5293–5313, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-5293-2017, 2017.

Addor, N., Nearing, G., Prieto, C., Newman, A. J., Le Vine, N., and Clark, M. P.: A Ranking of Hydrological Signatures Based on Their Predictability in Space, Water Resour. Res., 54, 8792–8812, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR022606, 2018.

Almagro, A., Meira Neto, A. A., Vergopolan, N., Roy, T., Troch, P. A., and Oliveira, P. T. S.: The Drivers of Hydrologic Behavior in Brazil: Insights From a Catchment Classification, Water Resour. Res., 60, e2024WR037212, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024WR037212, 2024.

Anderson, B. J., Slater, L. J., Dadson, S. J., Blum, A. G., and Prosdocimi, I.: Statistical Attribution of the Influence of Urban and Tree Cover Change on Streamflow: A Comparison of Large Sample Statistical Approaches, Water Resour. Res., 58, e2021WR030742, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030742, 2022.

Anderson, B. J., Brunner, M. I., Slater, L. J., and Dadson, S. J.: Elasticity curves describe streamflow sensitivity to precipitation across the entire flow distribution, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 28, 1567–1583, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-28-1567-2024, 2024.

Anderson, B. J., Slater, L. J., Rapson, J., Brunner, M. I., Dadson, S. J., Yin, J., and Buechel, M.: Stationarity Assumptions in Streamflow Sensitivity to Precipitation May Bias Future Projections, Earths Future, 13, e2025EF006188, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EF006188, 2025.

Andréassian, V., Coron, L., Lerat, J., and Le Moine, N.: Climate elasticity of streamflow revisited – an elasticity index based on long-term hydrometeorological records, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 20, 4503–4524, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-20-4503-2016, 2016.

Andréassian, V., Guimarães, G. M., Lerat, J., and de Lavenne, A.: Streamflow elasticity as a function of aridity, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2025-4912, 2025a.

Andréassian, V., Guimarães, G. M., de Lavenne, A., and Lerat, J.: Time shift between precipitation and evaporation has more impact on annual streamflow variability than the elasticity of potential evaporation, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 29, 5477–5491, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-29-5477-2025, 2025b.

Awasthi, C., Vogel, R. M., and Sankarasubramanian, A.: Regionalization of Climate Elasticity Preserves Dooge's Complementary Relationship, Water Resour. Res., 60, e2023WR036606, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023WR036606, 2024.

Ban, Z., Das, T., Cayan, D., Xiao, M., and Lettenmaier, D. P.: Understanding the Asymmetry of Annual Streamflow Responses to Seasonal Warming in the Western United States, Water Resour. Res., 56, e2020WR027158, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR027158, 2020.

Berghuijs, W. R., Hartmann, A., and Woods, R. A.: Streamflow sensitivity to water storage changes across Europe, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 1980–1987, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL067927, 2016.

Berghuijs, W. R., Larsen, J. R., van Emmerik, T. H. M., and Woods, R. A.: A Global Assessment of Runoff Sensitivity to Changes in Precipitation, Potential Evaporation, and Other Factors, Water Resour. Res., 53, 8475–8486, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017WR021593, 2017.

Budyko, M. I.: Climate and life, No. 18; International Geophysics Series, Academic Press, ISBN 9780080954530, 1974.

Chiew, F. H. S.: Estimation of rainfall elasticity of streamflow in Australia, Hydrol. Sci. J., 51, 613–625, https://doi.org/10.1623/hysj.51.4.613, 2006.

Chiew, F. H. S., Potter, N. J., Vaze, J., Petheram, C., Zhang, L., Teng, J., and Post, D. A.: Observed hydrologic non-stationarity in far south-eastern Australia: implications for modelling and prediction, Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess., 28, 3–15, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-013-0755-5, 2014.

Clerc-Schwarzenbach, F., Selleri, G., Neri, M., Toth, E., van Meerveld, I., and Seibert, J.: Large-sample hydrology – a few camels or a whole caravan?, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 28, 4219–4237, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-28-4219-2024, 2024.

Coxon, G., Addor, N., Bloomfield, J. P., Freer, J., Fry, M., Hannaford, J., Howden, N. J. K., Lane, R., Lewis, M., Robinson, E. L., Wagener, T., and Woods, R.: CAMELS-GB: hydrometeorological time series and landscape attributes for 671 catchments in Great Britain, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 12, 2459–2483, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-2459-2020, 2020a.

Coxon, G., Addor, N., Bloomfield, J. P., Freer, J., Fry, M., Hannaford, J., Howden, N. J. K., Lane, R., Lewis, M., Robinson, E. L., Wagener, T., and Woods, R.: Catchment attributes and hydro-meteorological timeseries for 671 catchments across Great Britain (CAMELS-GB), UKCEH [data set], https://doi.org/10.5285/8344e4f3-d2ea-44f5-8afa-86d2987543a9, 2020b.

de Lavenne, A., Andréassian, V., Crochemore, L., Lindström, G., and Arheimer, B.: Quantifying multi-year hydrological memory with Catchment Forgetting Curves, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 26, 2715–2732, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-26-2715-2022, 2022.

Dolich, A., Espinoza, E. A., Ebeling, P., Guse, B., Götte, J., Hassler, S., Hauffe, C., Kiesel, J., Heidbüchel, I., Mälicke, M., Müller-Thomy, H., Stölzle, M., Tarasova, L., and Loritz, R.: CAMELS-DE: hydrometeorological time series and attributes for 1582 catchments in Germany (1.0.0), Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13837553, 2024.

Dooge, J. C.: Sensitivity of runoff to climate change: A Hortonian approach, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 73, 2013–2024, 1992.

Dormann, C. F., Elith, J., Bacher, S., Buchmann, C., Carl, G., Carré, G., Marquéz, J. R. G., Gruber, B., Lafourcade, B., Leitão, P. J., Münkemüller, T., McClean, C., Osborne, P. E., Reineking, B., Schröder, B., Skidmore, A. K., Zurell, D., and Lautenbach, S.: Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance, Ecography, 36, 27–46, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2012.07348.x, 2013.

Fowler, K., Zhang, Z., and Hou, X.: CAMELS-AUS v2: updated hydrometeorological timeseries and landscape attributes for an enlarged set of catchments in Australia (2.03), Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14289037, 2024.

Fowler, K. J. A., Zhang, Z., and Hou, X.: CAMELS-AUS v2: updated hydrometeorological time series and landscape attributes for an enlarged set of catchments in Australia, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 17, 4079–4095, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-4079-2025, 2025.

Fu, G., Charles, S. P., and Chiew, F. H. S.: A two-parameter climate elasticity of streamflow index to assess climate change effects on annual streamflow, Water Resour. Res., 43, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007WR005890, 2007.

Gnann, S.: SebastianGnann/Streamflow_sensitivities: First release (v1.0.0), Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18302902, 2026.

Harman, C. J., Troch, P. A., and Sivapalan, M.: Functional model of water balance variability at the catchment scale: 2. Elasticity of fast and slow runoff components to precipitation change in the continental United States, Water Resour. Res., 47, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009656, 2011.

Harrigan, S., Hannaford, J., Muchan, K., and Marsh, T. J.: Designation and trend analysis of the updated UK Benchmark Network of river flow stations: the UKBN2 dataset, Hydrol. Res., 49, 552–567, https://doi.org/10.2166/nh.2017.058, 2018.

Institute of Hydrology: Low flow studies report No. 1: Research report, Wallingford, UK: Institute of Hydrology, 1980.

Kratzert, F., Nearing, G., Addor, N., Erickson, T., Gauch, M., Gilon, O., Gudmundsson, L., Hassidim, A., Klotz, D., Nevo, S., Shalev, G., and Matias, Y.: Caravan – A global community dataset for large-sample hydrology, Sci. Data, 10, 61, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-01975-w, 2023.

Kratzert, F., Nearing, G., Addor, N., Erickson, T., Gauch, M., Gilon, O., Gudmundsson, L., Hassidim, A., Klotz, D., Nevo, S., Shalev, G., and Matias, Y.: Caravan – A global community dataset for large-sample hydrology (1.6), Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7944025, 2025.

Lebecherel, L., Andréassian, V., and Perrin, C.: On regionalizing the Turc–Mezentsev water balance formula, Water Resour. Res., 49, 7508–7517, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR013575, 2013.

Lehner, F., Wood, A. W., Vano, J. A., Lawrence, D. M., Clark, M. P., and Mankin, J. S.: The potential to reduce uncertainty in regional runoff projections from climate models, Nat. Clim. Change, 9, 926–933, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0639-x, 2019.

Loritz, R., Dolich, A., Acuña Espinoza, E., Ebeling, P., Guse, B., Götte, J., Hassler, S. K., Hauffe, C., Heidbüchel, I., Kiesel, J., Mälicke, M., Müller-Thomy, H., Stölzle, M., and Tarasova, L.: CAMELS-DE: hydro-meteorological time series and attributes for 1582 catchments in Germany, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 16, 5625–5642, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-5625-2024, 2024.

Matanó, A., Hamed, R., Brunner, M. I., Barendrecht, M. H., and Van Loon, A. F.: Drought decreases annual streamflow response to precipitation, especially in arid regions, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 29, 2749–2764, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-29-2749-2025, 2025.

McMillan, H. K., Krueger, T., and Freer, J. E.: Benchmarking observational uncertainties for hydrology: Rainfall, river discharge and water quality, Hydrol. Process., 26, 4078–4111, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9384, 2012.

McMillan, H. K., Westerberg, I. K., and Krueger, T.: Hydrological data uncertainty and its implications, WIREs Water, 5, e1319, https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1319, 2018.

Milly, P. C. D. and Dunne, K. A.: Potential evapotranspiration and continental drying, Nat. Clim. Change, 6, 946–949, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3046, 2016.

Němec, J. and Schaake, J.: Sensitivity of water resource systems to climate variation, Hydrol. Sci. J., 27, 327–343, https://doi.org/10.1080/02626668209491113, 1982.

Newman, A. J., Clark, M. P., Sampson, K., Wood, A., Hay, L. E., Bock, A., Viger, R. J., Blodgett, D., Brekke, L., Arnold, J. R., Hopson, T., and Duan, Q.: Development of a large-sample watershed-scale hydrometeorological data set for the contiguous USA: data set characteristics and assessment of regional variability in hydrologic model performance, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 19, 209–223, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19-209-2015, 2015.

Newman, A. J., Sampson, K., Clark, M., Bock, A., Viger, R., Blodgett, D., Addor, N., and Mizukami, M: CAMELS: Catchment Attributes and MEteorology for Large-sample Studies (1.2), Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5065/D6MW2F4D, 2022.

Nijssen, B., O'Donnell, G. M., Hamlet, A. F., and Lettenmaier, D. P.: Hydrologic Sensitivity of Global Rivers to Climate Change, Clim. Change, 50, 143–175, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010616428763, 2001.

Nijzink, R. C. and Schymanski, S. J.: Vegetation optimality explains the convergence of catchments on the Budyko curve, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 26, 6289–6309, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-26-6289-2022, 2022.

Peterson, T. J., Saft, M., Peel, M. C., and John, A.: Watersheds may not recover from drought, Science, 372, 745–749, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd5085, 2021.

Roderick, M. L. and Farquhar, G. D.: A simple framework for relating variations in runoff to variations in climatic conditions and catchment properties, Water Resour. Res., 47, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009826, 2011.

Saft, M., Western, A. W., Zhang, L., Peel, M. C., and Potter, N. J.: The influence of multiyear drought on the annual rainfall-runoff relationship: An Australian perspective, Water Resour. Res., 51, 2444–2463, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014WR015348, 2015.

Sankarasubramanian, A., Vogel, R. M., and Limbrunner, J. F.: Climate elasticity of streamflow in the United States, Water Resour. Res., 37, 1771–1781, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000WR900330, 2001.

Sawicz, K., Wagener, T., Sivapalan, M., Troch, P. A., and Carrillo, G.: Catchment classification: empirical analysis of hydrologic similarity based on catchment function in the eastern USA, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 15, 2895–2911, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-15-2895-2011, 2011.

Schaake, J. C.: From climate to flow., John Wiley and Sons Inc., New York, 177–206, ISBN 978-0-471-61838-6, 1990.

Sen, P. K.: Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall's Tau, J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 63, 1379–1389, https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1968.10480934, 1968.

Steinschneider, S., Yang, Y.-C. E., and Brown, C.: Panel regression techniques for identifying impacts of anthropogenic landscape change on hydrologic response, Water Resour. Res., 49, 7874–7886, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR013818, 2013.

Tang, Y., Tang, Q., Wang, Z., Chiew, F. H. S., Zhang, X., and Xiao, H.: Different Precipitation Elasticity of Runoff for Precipitation Increase and Decrease at Watershed Scale, J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, 124, 11932–11943, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD030129, 2019.

Tang, Y., Tang, Q., and Zhang, L.: Derivation of Interannual Climate Elasticity of Streamflow, Water Resour. Res., 56, e2020WR027703, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR027703, 2020.

Turner, S., Hannaford, J., Barker, L. J., Suman, G., Killeen, A., Armitage, R., Chan, W., Davies, H., Griffin, A., Kumar, A., Dixon, H., Albuquerque, M. T. D., Almeida Ribeiro, N., Alvarez-Garreton, C., Amoussou, E., Arheimer, B., Asano, Y., Berezowski, T., Bodian, A., Boutaghane, H., Capell, R., Dakhaoui, H., Daòhelka, J., Do, H. X., Ekkawatpanit, C., El Khalki, E. M., Fleig, A. K., Fonseca, R., Giraldo-Osorio, J. D., Goula, A. B. T., Hanel, M., Horton, S., Kan, C., Kingston, D. G., Laaha, G., Laugesen, R., Lopes, W., Mager, S., Rachdane, M., Markonis, Y., Medeiro, L., Midgley, G., Murphy, C., O'Connor, P., Pedersen, A. I., Pham, H. T., Piniewski, M., Renard, B., Saidi, M. E., Schmocker-Fackel, P., Stahl, K., Thyer, M., Toucher, M., Tramblay, Y., Uusikivi, J., Venegas-Cordero, N., Visessri, S., Watson, A., Westra, S., and Whitfield, P. H.: ROBIN: Reference observatory of basins for international hydrological climate change detection, Sci. Data, 12, 654, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04907-y, 2025.

Wagener, T., Reinecke, R., and Pianosi, F.: On the evaluation of climate change impact models, WIREs Clim. Change, 13, e772, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.772, 2022.

Weiler, M., Gnann, S., and Stahl, K.: Streamflow sensitivity regimes of alpine catchments: seasonal relationships with elevation, temperature, and glacier cover, Environ. Res. Lett., 20, 074068, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ade26c, 2025.

Woods, R. A.: Analytical model of seasonal climate impacts on snow hydrology: Continuous snowpacks, Adv. Water Resour., 32, 1465–1481, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2009.06.011, 2009.

Xiao, M., Gao, M., Vogel, R. M., and Lettenmaier, D. P.: Runoff and Evapotranspiration Elasticities in the Western United States: Are They Consistent With Dooge's Complementary Relationship?, Water Resour. Res., 56, e2019WR026719, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR026719, 2020.

Zhang, L., Dawes, W. R., and Walker, G. R.: Response of mean annual evapotranspiration to vegetation changes at catchment scale, Water Resour. Res., 37, 701–708, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000WR900325, 2001.

Zhang, Y., Viglione, A., and Blöschl, G.: Temporal Scaling of Streamflow Elasticity to Precipitation: A Global Analysis, Water Resour. Res., 58, e2021WR030601, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030601, 2022.

Zhang, Y., Zheng, H., Zhang, X., Leung, L. R., Liu, C., Zheng, C., Guo, Y., Chiew, F. H. S., Post, D., Kong, D., Beck, H. E., Li, C., and Blöschl, G.: Future global streamflow declines are probably more severe than previously estimated, Nat. Water, 1, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-023-00030-7, 2023.

Zhou, S., Yu, B., Huang, Y., and Wang, G.: The complementary relationship and generation of the Budyko functions, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, 1781–1790, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL063511, 2015.