the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Will groundwater-borne nutrients affect river eutrophication in the future? A multi-tracer study along the Elbe River

Julia Zill

Axel Suckow

Ulf Mallast

Jürgen Sültenfuß

Axel Schmidt

Christian Siebert

The Elbe River drains an intensely used agricultural area and cuts through a series of consolidated and unconsolidated aquifers with heterogeneous hydraulic properties and dimensions. For decades and as a result of overfertilization, particularly in the former GDR, the hosted groundwater transport nutrients into the river with serious implications for water quality and ecosystem health. As fertilization practices changed over time, nutrient loads in the groundwater recharge declined since the 1990s. This study investigates the residence time scales of groundwater along the river, as a measure to estimate the input periods of the associated nutrients entering the river using multi-environmental tracers (, SF6, CFCs, 14C). By applying lumped parameter models, we conclude that the average ages of groundwater range from a few up to 41 years, with infiltration occurring predominantly after 1985. Our results identify a young groundwater system with measurable denitrification and minimal to moderate admixtures of older water fractions clearly discernible with 4He. That indicates, the groundwater that was recharged during the GDR period (1945–1989) at maximum fertilizer application has already run off, the nutrient concentrations in the groundwater have peaked and may continue to decline in the coming decades. These results are crucial for informing river basin management strategies aimed at mitigating eutrophication and protecting aquatic ecosystems. It provides valuable insights into the temporal dynamics of groundwater contributions to surface waters and their regional implications for sustainable resource management.

- Article

(5541 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(977 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

In Central Europe, as in most regions worldwide, groundwater is a significant source of both nutrients and contaminants entering riverine systems (Shishaye et al., 2021). A potential source is the intense application of N-fertilisers, including slurry, that leads to large inputs of nitrate through agricultural land into the groundwater (van der Grift et al., 2016; Craswell, 2021; Chen et al., 2023), which may discharge as base flow into surface waters. This enhances the vulnerability towards eutrophication (Brookfield et al., 2021; Zill et al., 2024) and, thus jeopardising ecosystem stability (Dodds, 2006) downstream to the ocean. During the last decades, important catchment decisions significantly reduced the application of liquid manure and mineral N-fertilisers in Germany and Europe: i.e. the 1989 political revolution in Eastern Germany, the 1991 EU Council Directive to protect waters against pollution by nitrate (91/676/EWG), the year 2000 implementation of the European Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EG), the 2017 German Fertiliser Ordinance (DüV2017) and in its 2020 modified form (DüV2020). Nevertheless, to assess the possible future trends of nutrient loads in rivers, it would be beneficial to link the current nutrient concentrations (such as NO3 and PO4) in potentially contributing aquifers to specific periods of past fertilizer use. Sanford and Pope (2013) and Martin et al. (2017) highlight the significance of understanding these timescales, as it is difficult to establish and achieve objectives for preserving surface water quality and evaluating the effects of groundwater-borne nutrients on river systems without this knowledge. This understanding could facilitate the development of regionally specific interventions and the implementation of effective management strategies to reduce eutrophication and safeguard aquatic ecosystems.

Furthermore, the study of groundwater age distributions and mean residence times is valuable for several other reasons (Dagan, 1986; Dagan and Nguyen, 1989), as it allows the validation of groundwater models, ensuring their accuracy and reliability (Sanford, 2011; Schilling et al., 2019; Ying et al., 2024). Understanding age distributions helps in quantifying groundwater infiltration and recharge rates, which are essential for water resources management. Gilmore et al. (2016) emphasise the significance of accurately determining groundwater flow paths from the source to the discharge areas, being important in revealing the transport behaviour of both temporary and persistent contaminants. Investigating groundwater age as tracer age provides a deeper understanding of flow processes within the aquifer, contributing to more effective groundwater management practices. And, assessing tracer age is relevant for determining the vulnerability of the aquifer and establishing protection zones, such as those for drinking water (Molson and Frind, 2012) or groundwater-dependent areas in general (Isokangas et al., 2017).

However, groundwater samples taken at one point represent an inextricable mix of water having observed short and long flow paths and therefore containing fractions of very different ages. The age distribution rather than the “mean groundwater age” is therefore the essential measure for precise root-cause analysis and the assessment of the vulnerability of a groundwater body with regard to contaminants or nutrients (McCallum et al., 2014; Suckow, 2014). Determining the age distribution as a whole is, however, only possible in exceptional cases with a very long time series of tracer measurements (Suckow and Gerber, 2022). Therefore, instead of a single tracer (radioisotopes, stable isotopes or hydrochemical parameters), a combination of natural geochemical or isotopic tracers must be used and analysed. These multi-environmental tracer studies often cover different time scales (Corcho Alvarado et al., 2007; Mayer et al., 2014; Purtschert et al., 2023). Younger fractions can be determined using 3H and tritiogenic 3Hetrit (Sültenfuß and Massmann, 2004; Desens et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023), anthropogenic gases like SF6, CFC-11, CFC-12 (Daughney et al., 2010; Okofo et al., 2022) and 85Kr (Cook and Solomon, 1997; Kagabu et al., 2017). Older water fractions are estimated by 14C (Maloszewski and Zuber, 1991; Iverach et al., 2017), 36Cl (Wilske et al., 2020; Purtschert et al., 2023) or 4He (Matsumoto et al., 2018). Even with multi-tracer applications the details of the age distributions can only be pinpointed with a high level of uncertainty (McCallum et al., 2014), but nevertheless, this remains the state-of-the art approach. Only knowledge of the different groundwater age fractions and their spatial distribution in the subsurface offers the possibility of understanding the vulnerability of the aquifer and its negative influence on surface waters through possible groundwater - surface water interactions. To obtain mean residence times from tracer measurements, lumped parameters models (LPM), which are detailed in Maloszewski and Zuber (1996) and Suckow (2014) are powerful tools. In essence, Lumped Parameter Models (LPMs) are analytical solutions characterized by a limited number of key parameters and a simplified aquifer structure. They employ a mathematical age distribution to compute Mean Residence Times (MRTs) based on sampled tracer concentrations.

All nutrients in the aquifer are subject to dispersion and diffusion effects. With regard to the entry paths of N and P species into watercourses, their different physico-chemical characteristics must be taken into account. In contrast to phosphate, nitrate does not adsorb significantly to minerals and soil particles, which results in direct surface runoff into the receiving waters. These only reach the river systems with a corresponding time delay (legacy effect – Lautz et al., 2020; Martin et al., 2021; Shishaye et al., 2021), which makes it difficult to predict nutrient concentrations (Kunkel and Wendland, 2006; Martin et al., 2017). The calibration and validation of process-based models is possible for small-scale (a few km2) applications, but there is still a need for research into their transferability to large-scale issues (>100 km2) (Briggs and Hare, 2018). Due to the extreme chemical heterogeneity at the interfaces of groundwater and surface water, in connection with seasonally variable parameters like water level, oxygen or nutrient concentrations, a generalised prediction of the influence of groundwater on ecosystems is not possible. For this, catchment-specific regional studies must be used and limiting factors such as usable pore volume, hydraulic connectivity, temperature, organic matter and riverine nutrient control mechanisms must be analysed.

This study aims to estimate time scales of groundwater movement and nutrient transport within several different aquifers along an almost 450 km stretch of the Elbe River in Central Germany. Earlier studies revealed the accompanying groundwaters are sources of nutrients in the Elbe River, affecting the food web and eutrophication of the river (Zill et al., 2023; 2024) and eventually the ocean (Kamjunke et al., 2023).

The studied groundwater bodies are located along the 450 km long stretch of the German Elbe River from Schöna at the Czech border to Wittenberge. The Elbe River is one of the largest rivers in Europe and shows strong eutrophication effects (Hardenbicker et al., 2016), being the major reason to downgrade its ecological state to “moderate/unsatisfactory”, according to the European water framework directive (UBA, 2022). The impact of groundwater-borne nutrients to the benthic and pelagic eutrophication of the Elbe River were studied by Zill et al. (2024) and show that groundwater contributes significantly to pelagic eutrophication and particularly under low flow conditions. Benthic eutrophication and the algae community are mainly dependent on the season and subsequently influenced by the aquifer type and groundwater discharge.

Zill et al. (2023) investigated the temporal and spatial interactions between groundwater and surface water along the Elbe River. Their findings reveal distinct differences in groundwater fluxes and resulting water quality. In the headwater regions, pronounced topography forces fast flow that leads to high groundwater discharge with low nutrient loads, as agricultural activity in these upstream catchments is minimal. In contrast, downstream lowland areas (Fig. 1B) show low natural groundwater inflow due to missing topographical gradients, while fertile soils lead to intense agriculture. The combination of both requires artificial dewatering of the fields by dikes and subsurface drainage systems, being both preferential channels to transport nutrient-rich soil water into the Elbe River. Their effect even increases during droughts, when hydraulic gradients are higher.

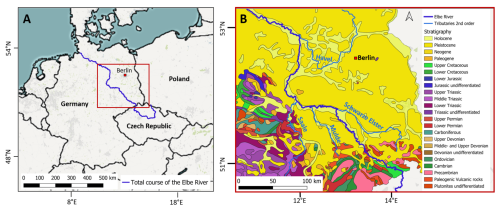

The hydrogeological situation in the study area is divided into two main settings (Fig. 1B). Within the first 100 stream km, the Elbe cuts through the hard rocks of the Saxonian Cretaceous, comprising the Elbtal group with coastal sandstones. Afterwards, the river runs through the mostly unconsolidated Pleistocene aquifers of the Middle German Lowland, which were deposited during glacial and interglacial periods (IKSE, 2005; Wilmsen and Niebuhr, 2014).

Figure 1Elbe River study area: (A) Location of the Elbe River in Central Europe. (B) Stratigraphic map of the study area. Base Maps derived from QGIS desktop and stratigraphic map derived from the geological map of Germany (GK2750) from the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR), Hannover.

The Pleistocene aquifers have a spatially variable permeability and a silicate, partly silicate-organic rock characteristic (Eissmann, 2002). The youngest deposits comprise an aquifer complex from Weichsel and Saale glacial period and are composed of ca. 20 m thick permeable fluvial sands and gravels. They are underlain by about 50 m of less permeable silty glauconite sands from the Elster glacial period. All the groundwater hosted in these formations drains towards the Elbe (Ad-Hoc-AG Hydrogeologie, 2016). The Cretaceous hard rocks consist of fissured and low to moderate hydraulic permeable sandstones, claystones, siltstones and bioturbated marlstones (Wilmsen and Niebuhr, 2014), forming an ca. 300 m thick complex of five aquifers, which predominantly drain towards the Elbe valley. In the Elbe valley and inside side valleys, groundwater tables are shallow, leading to a high vulnerability of the groundwater to contamination.

To determine the age scales of groundwater and of the carried nutrients, which flow into the Elbe River, all the groundwater bodies which most probably contribute were identified using hydrogeological and contourline maps. Groundwater was sampled from these aquifers during two sampling campaigns in 2020 and 2022 by pumping from observation wells that (i) tap the target aquifers and are (ii) preferably located in close proximity (within a maximum of 10 km) to the Elbe Valley. The groundwater has been analysed for environmental age tracers covering a wide range of age spectra: , SF6, CFCs, and 14C. Subsequently, the lumped parameter model LUMPY (Suckow, 2012) was applied, to estimate time scales of groundwater ages based on a convolution integral including atmospheric input functions, borehole parameters such as depth and screened sections and conceptual flow models (exponential models (EM), dispersion models (DM), and piston flow models (PFM)). They represent the individual aquifer types and regional conditions. By visual comparison, we selected the best model for our data set.

3.1 Fundamentals of the methods

Tritium (3H) is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a half-life of 12.32 years, naturally formed primarily in the atmosphere through spallation and neutron reactions of cosmic radiation with the atmosphere (Unterweger and Lucas, 2000). Its concentration is measured in activity units (Bq L−1). However, in environmental sciences, tritium concentrations are expressed in Tritium Units (TU). The conversion is 1 Bq L−1 = 8.47 TU (IAEA, 1992). In the hydrosphere, tritium becomes part of water molecules and reaches the Earth via precipitation. Atmospheric nuclear tests in the late 1950s and 1960s caused a dramatic increase in tritium concentrations, raising them far above the natural background level of ∼5 TU in the atmosphere (Clark and Fritz, 2013). Since the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, atmospheric tritium levels have declined due to radioactive decay and dilution in the oceans. Today, they reach approximately 8 TU in the Northern Hemisphere, with slightly higher levels during the early summer months (Schmidt et al., 2020).

The tritium-helium dating method, developed in the 1980s (Poreda et al., 1988; Schlosser et al., 1988), uses tritium and its decay product tritiogenic helium-3 (3Hetrit), to estimate groundwater age. This method assumes there is no other source of 3Hetrit than the decay of 3H, while 3Hetrit needs to be separated from other 3He sources. These are identified by measurements of 4He, which is produced from the decay of U and Th in the aquifer, and Ne (Schlosser et al., 1988). The sum of 3H and 3Hetrit reflects the initial 3H concentration at the time of water infiltration. Only in the absence of mixing and dispersion the so-called tritium-helium age indicates the advective groundwater velocity. Mixing or dispersion would bias results towards ages with higher tracer concentrations (Schlosser et al., 1988; Schlosser and Winckler, 2002). The tritium-helium age can be determined by the following equation:

With τtrit= tritium-helium age [a], λtrit= tritium decay constant [], 3Hetrit= tritiogenic helium-3 concentration [TU], 3H = tritium concentration [TU]. The concentration of 3Hetrit is determined from the helium and neon concentration on each sample using the formulas in Schlosser et al. (1988) and using a conversion factor of 1 cc(STP) g−1 = 4.019×1014 TU.

Radiocarbon (14C), with a half-life of 5730±40 years (Godwin, 1962), is used to estimate groundwater age by comparing the 14C concentration of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) at recharge with current levels. Two main challenges include estimating the initial 14C concentration at recharge and accounting for sub-surface dilution by 14C-free DIC from geochemical reactions during flow (Wigley et al., 1978; Plummer and Glynn, 2013). Atmospheric nuclear tests in the 1960s significantly increased 14C levels, complicating age estimates for groundwater recharged before this period (Levin and Kromer, 1997). For dating, the initial 14C concentration is typically assumed to be 100 pMC, reflecting pre-nuclear testing atmospheric CO2 levels (Pearson and White, 1967). DIC in groundwater primarily originates from (i) soil CO2 (high in 14C), where the CO2 is derived from root respiration and organic material turnover, rather than direct atmospheric CO2 and (ii) carbonate dissolution, where carbonates usually being low in 14C, except recently formed travertine (Geyh, 1970). Variations in atmospheric 14C, influenced by the earth's magnetic field, solar activity, and climate, can slightly alter age estimates, though these effects are minor compared to uncertainties from geochemical mixing of CO2 and CO3 into DIC (Pearson and Qua, 1993).

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and Sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) are anthropogenic gaseous pollutants, released into the atmosphere globally since the 1950s from industrial products and processes and enriched in the atmosphere over time. It is assumed that the accumulation of these gases in the atmosphere is in equilibrium with the concentration in surface waters at a given temperature and pressure. Their respective atmospheric concentrations are well documented over time, providing a continuous input function for groundwater dating, which is generally not the case for other gases. CFCs were introduced in 1930 for applications such as refrigeration, air conditioning, aerosol propellants, and plastic foams (IAEA, 2006). Their atmospheric concentration began decreasing only with the Montreal Protocol in 1987, which restricted CFC use to protect the ozone layer. In contrast, sulphur hexafluoride introduced in 1953 for use in gas-filled electrical switches, has seen a steady increase in the atmosphere until the present. Its low solubility in water and high stability in soils make it an effective tracer for dating young groundwater (Mroczek, 1997; Busenberg and Plummer, 2000). Groundwater dating with CFCs and SF6 depends on processes such as sorption, dispersion, and microbial degradation. SF6 is due to its resistance to degradation and limited affinity to sorption particularly reliable (Busenberg and Plummer, 2000). The method assumes equilibrium governed by Henry's Law of solubility, with key assumptions for recharge temperature, excess air entrainment, and unsaturated zone thickness (Aeschbach-Hertig et al., 1999; IAEA, 2006).

3.2 Groundwater sampling

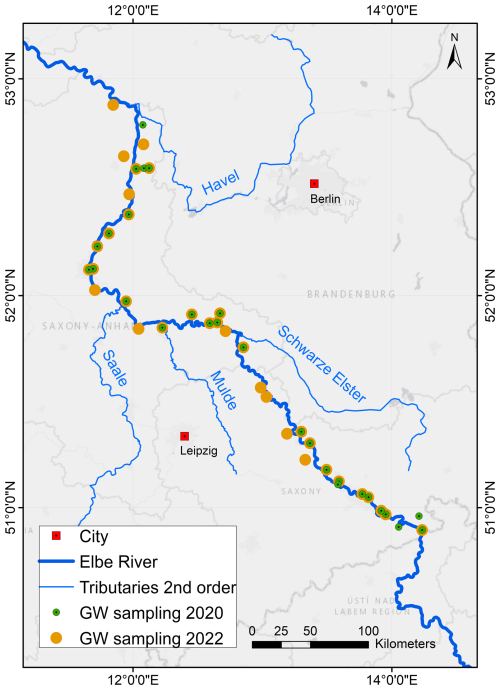

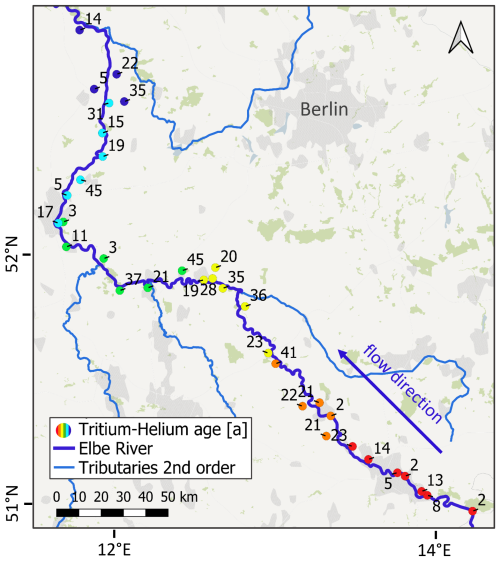

During spring 2020 and 2022, 63 boreholes and springs were sampled for groundwater from the shallow aquifers that are in hydraulic connection with the Elbe River. The selected wells are located along 450 km of the river's course (Fig. 2). In the Saxonian Sandstone Mountain aquifers, where wells were unavailable, samples were taken from springs. All sampling locations and analytical results are listed in detail in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplement. Groundwater was extracted using a Grundfos MP1 submersible pump (Eijkelkamp, the Netherlands). Samples were collected after the standing water in the boreholes was replaced three times and on-site parameters (pH, temperature, Eh and EC; measured with multiparameter WTW 350i (WTW, Germany)) stabilised.

Figure 2Map of all groundwater sampling locations from 2020 (green) and 2022 (orange) along the German Elbe River.

Samples for 3H were filled in clean 500 mL HDPE containers. Duplicate samples for 3He were filled carefully without air inclusions into 40 mL copper pipes of 1 m length, which were closed under pressure. The samples for CFC-11, CFC-12 and SF6 were taken by filling a 10 L HDPE container with the water sample by overflow principle. Afterwards the container was closed without air inclusion. From below, purified N2-gas (Linde, Germany) was injected into the system to replace about 200 mL of water and to generate a N2-headspace. The closed system was then shaken for a minimum of 20 min to ensure the degassing of water and equilibration with the headspace. Afterwards, parts of the headspace were extracted at field temperature and injected into 20 mL glass vials, which have been evacuated and N2-flushed prior to sampling. Samples for were filled in clean 60 L HDPE containers to ensure sufficient amounts of DIC, while samples for on water and on dissolved NO3 were sterile filtered applying 0.22 µm filter (Sartobran, Sartorius, Germany) and filled into pre-cleaned HDPE containers. All samples were stored dark and cool until laboratory analysis.

3.3 Analytical methods

The preparation of water samples for tritium analysis follows the method outlined by Schmidt et al. (2020). This involves the electrolytic enrichment of a 300–500 mL water sample, followed by measurement using liquid scintillation counting. The technique achieves a detection limit of 0.5 TU, with a relative standard error of 10 % for 3H concentrations above 0.5 TU. All analyses were performed using different liquid scintillation counters (TriCarb 3180, Quantulus GCT 6220, PerkinElmer, Germany; Hidex 300 SL, Hidex Oy, Finland). The preparation and measurement of helium isotopes and neon in water samples follow the procedure described by Sültenfuß et al. (2009). In summary, gas is extracted from water contained in copper tubes and transferred into glass ampoules. For measurement, an ampoule is opened in a high-vacuum system, and the gases are transferred to low-temperature traps. Using a cryo trap at 25 K, He and Ne are separated from other gases. A fraction of the He–Ne mixture is analysed for 4He, 20Ne, and 22Ne using a quadrupole mass spectrometer (QMG 112, Pfeiffer Vacuum, Germany). The remaining gases are adsorbed to activated carbon in a low-temperature trap at 10 K, and after heating to 45 K, only He desorbs. This fraction is then analysed for 3He and 4He in a sector field mass spectrometer (MAP 215-50). The system was calibrated with atmospheric air, achieving a measurement accuracy of 0.4 % for and ratios, and 0.7 % for isotope concentrations (1σ confidence interval; Sültenfuß et al., 2009).

The preparation and measurement of anthropogenic gases, including CFC-11, CFC-12, and SF6, follow a method adapted from Busenberg and Plummer (2008). In this procedure, septum glass tubes are connected to a Rheodyne 6-way valve (Supleco, USA) with two operational positions: “load” (position I) and “inject” (position II). In the “load” position, the sample is directed into a stainless-steel trap (WICOM, Germany) filled with Porapak T and cooled to −70 °C. The trap is flushed with nitrogen at 50 mL min−1, then heated to 95 °C to release the tracers. When the valve is switched to the “inject” position, the sample is directed into a gas chromatograph (GC-2014, Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with an electron capture detector (ECD). Helium is used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 30 mL min−1. The GC system includes a pre-column (1 m; heated to 80 °C) and main column (3 m; heated to 180 °C), both filled with HayeSep Q. Specific elution times are observed for SF6, CFC-12, and CFC-11 at 4.5, 17.5, and 31.1 min, respectively. The ECD operates at 300 °C to ensure precise detection. The system was calibrated with gas standards from the University of Bremen, achieving an analytical uncertainty of ∼2 % for SF6 and CFCs.

The radiocarbon analyses were performed by liquid scintillation counting (Tri-Carb 3770 TR/SL, Perkin Elmer). First, BaCl2 was added to the alkalized water samples to precipitate DIC as BaCO3. Afterwards, precipitated carbon is transferred into CO2 and further transformed into lithium carbide, acetylene and finally into benzene. NBS oxalic acids (USA) and ANU sucrose (Australia) were used as standards (Trettin et al., 2006). For δ13C, part of the formed CO2 was captured separately and kept for stable carbon isotope analysis in an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Delta plus XL, Thermo Quest, Germany). As an internal standard, BaCO3 was used which was calibrated on the international V-PDB (Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite) standard.

The stable isotopes of water (δ2H and δ18O) were measured by laser cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS) using a Picarro L2120-1 (Picarro, USA). The analytical precision is ±0.1 ‰ for δ18O and ±0.8 ‰ for δ2H and results are reported relative to Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (V-SMOW). Nitrate was measured with ion chromatography (Dionex ICS-2000, Thermo Scientific, Germany) and the δ15N and δ18O signatures of dissolved NO3 were determined with a denitrifier method using bacteria strains of Pseudomonas chlororaphis (Sigman et al., 2001). Using a GasBench II with an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (DELTA V Plus, Thermo Scientific, Germany), the resulting N2O gas from microbial production was measured. The analytical precision is ±0.4 ‰ for δ15N and ±0.8 ‰ for δ18O.

3.4 Modelling

Lumped parameter models (LPMs) are predefined analytical solutions for simplified flow systems that conceptualise the entire aquifer as a spatially zero-dimensional system. The theoretical basis of LPMs is described in detail by Małoszewski and Zuber (1982), Han and Maloszewski (2006), and the IAEA (2006). Mathematically, LPMs are represented by a convolution integral, which integrates the time-dependent input function using the age distribution as a weighting function. The concentration of a certain substance, the “tracer”, in groundwater sampled at a well or spring can be described by this convolution integral, while the fitting parameter is the mean residence time (MRT):

With Cout= output concentration, time dependent sampled input concentration, t = time, t′ = transit time or input time, g(t′) = the age distribution, a weighting function that is normalised to 1. The MRT and in some cases a secondary parameter such as the Péclet number characterise the shape of the age distribution g(t′).

In our study the LPM LUMPY was used (Suckow, 2012), which is part of the graphical user interface of the LabData Database and Laboratory Management System from Suckow and Dumke (2001). The algorithm of LabData allows the modelling of several tracers simultaneously, while the flow within the aquifers were conceptualized by an exponential model (EM), a piston flow model (PFM) and a dispersion model (DM). The LPM lines in the following figures are for orientation purposes only. A PFM is conceptually the simplest of all approaches and describes a flow path in the aquifer without any mixing, diffusion or dispersion. The resulting age distribution therefore contains exactly one age, so that for this model the MRT and the idealised age are the same. An EM describes a completely mixed aquifer (Eriksson, 1971) in a homogenous, unconfined system. The vertical zonation of the groundwater age implies young ages at the groundwater table, increasing to infinity at the aquifer's base (Vogel, 1970; Appelo and Postma, 1996). A DM is characterised by the MRT and the Péclet number Pe, which relates the magnitudes of dispersion and advection and is defined according to Eq. (3):

With l= characteristic length of the flow path [m], v= advective transport [m s−1], D= dispersive transport [m2 s−1].

Using a small Péclet number such as 4, results from a DM are very similar to an EM.

4.1 Stable isotopes

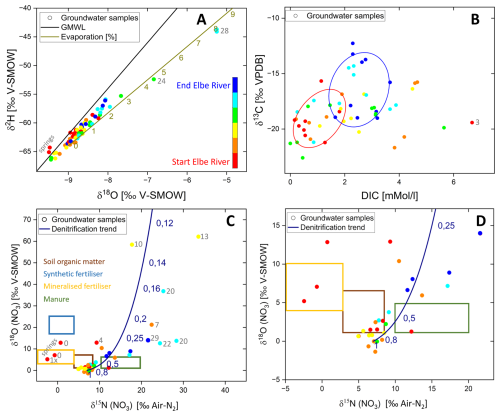

The stable isotopic signatures (δ2H and δ18O) of the sampled groundwater plot along the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL: O+9 (Gat et al., 2001)), indicating low evaporation prior to infiltration (Fig. 3A). The signatures range from −67 ‰ to −44 ‰ for δ2H and from −9.5 ‰ to −5.5 ‰ for δ18O. Taking water sample #12 and calculating a theoretical evaporation line (at 60 % humidity and 20 °C), only samples #24 and #28 were exposed to higher evaporation (4.5 % and 8 %, respectively) compared to all others. The two springs in Saxony have isotopic signatures slightly above the GMWL. The δ13C signatures of the sampled groundwater range from −23 ‰ to −12 ‰ V-PDB (Fig. 3B). This mass range corresponds to carbon sources primarily derived from root respiration of C3 plants and dissolution of freshwater carbonates (Meier-Augenstein, 1999). Additionally, distinct clusters (covering over 80 % of all corresponding samples) of carbon species are discernible, with varying initial concentrations of DIC detected among the samples. DIC concentrations range from 0 to 6.7 mMol L−1, with sample #3 showing the highest value of 6.7 mMol L−1. The δ15N in nitrate reveals significant enrichment, with δ15N values around +8 ‰ and δ18O (NO3) values approximately +2 ‰ V-SMOW (Fig. 3C), with sources of nitrate partly from soil organic matter (Fig. 4D). Three groundwater samples from the Cretaceous aquifers show sources of mineralised fertiliser or manure (Fig. 4D, orange and green rectangle). No consistent nitrate enrichment trend is evident, and a simple Rayleigh fractionation calculation indicates that most samples observed less than 70 % denitrification (30 % residual) (Fig. 3C and D, blue line) suggesting low to moderate denitrification rates within the different aquifer systems. However, samples #7, #10, #13, #20, #22, #29 show high denitrification rates over 75 % with NO3 concentrations close to the detection limit (see Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplement).

Figure 3(A) shows δ2H versus δ18O signatures in the sampled groundwaters. The khaki evaporation line indicates an accumulation of heavier isotopes through evaporation along the line. Numbers show evaporation rates in %. For better spatial orientation: Start and end of the Elbe River stands for groundwater samples which were taken from aquifers located along the start (warm colours) or end (cold colours) of the studied Elbe section, respectively. This color code was applied in panels (A) to (D). (B) shows δ13C signatures of DIC in relation to DIC in the sampled groundwater along the Elbe River. (C) shows δ18O versus δ15N signatures of nitrate in the sampled groundwaters. The dark blue line shows Rayleigh fractionation of nitrate isotopes where the dark blue numbers present the non-fractionated part (remaining fraction of the initial NO3 pool). Coloured frames show different nitrate sources according to Clark and Fritz (2013) of soil organic matter (brown), synthetic and mineralised fertiliser (blue and yellow, respectively) and manure (green). (D) shows a zoom into panel (C) with the same nitrate sources as in panel (C).

4.2 Environmental age tracers

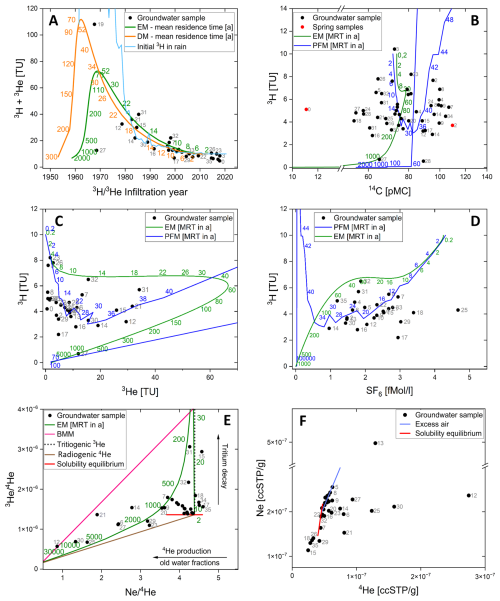

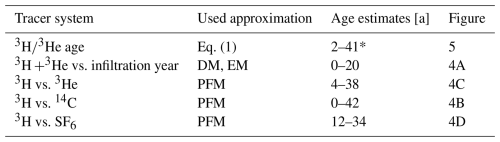

Representative results from lumped parameter modelling are shown in Fig. 4A to F.

In Fig. 4A, the initial tritium concentration (3H + 3He) is plotted against the infiltration year, suggesting mean residence times between 0 and 20 years, when using a dispersion model (DM) with a Péclet number of 4. Samples (e.g., #17 and #27) with concentrations below the levels found in the models (green and orange line, Fig. 4A) are indicative for a mixture with older, tritium-free groundwater that was recharged before the bomb tests in the 60 s. Sample #27, in particular, is tritium-free water with no detectable proportion of younger recharge and a major composition of an old water fraction (>60 years). Conversely, samples with concentrations exceeding the precipitation level (e.g., #19, #31, #32) suggest the influence of water sources with elevated tritium levels, such as the cooling water release from the Czech nuclear power plant Temelín (Hanslík et al., 2017; Zill et al., 2023). Bank-filtrate could enhance 3H concentrations in groundwater as in sample #19, which is located along a stretch of the Elbe, where influent conditions prevail at least during times of low flow (Zill et al., 2023). This may exhibit anomalously high 3He values, accompanied by moderate 3H concentrations of 5.7 TU. The 3H concentrations in the collected groundwater samples are on average 5 TU and the corresponding ages indicate residence times ranging from 2 to 52 years (Fig. 5). ages exceeding 45 years are considered unreliable as their calculations are based on the detection limit in tritium (#27) or influenced by admixtures from the tritium peak and resulting high 3He (#19) concentrations (Fig. 4C). These ages are therefore labelled as >45 years in Fig. 5.

Even if a high proportion of young water is generally evident, tracers for older water such as 4He (Fig. 4E and F, discussed below) or radiocarbon (Fig. 4B) indicate an admixture of old water components for some samples (e.g. #0, #18, #24, #27, #28). Comparing young water fractions represented by 3H, with old water fractions represented by 14C, show noticeable deviations of groundwater samples from modelled graphs like an EM or a PFM (Fig. 4B). Most of the variation along the 14C axis in Fig. 4B can be explained by geochemical reactions of the DIC under open or closed system conditions, diluting the atmospheric 14C signal with 14C-free sedimentary carbon. However, springwater samples (Fig. 4B, red points) consistently appear as outliers. Sample #0 with 11 pMC shows a major contribution from old water fractions, while #2 with 117 pMC shows an infiltration about the time of nuclear bomb tests in the 1960s (as 100 pMC is by definition the year 1950). The contaminated sample #1 that can not be shown in the figures is the Mockenthal spring, which shows 14C values of 373 pMC and 3H values of 88 TU and 102 TU in 2020 and 2022, respectively. This is most probably a result of anthropogenic contamination by legacies from an abandoned military base or from the former repository of the GDR period in the catchment and therefore excluded from the analyses. A cluster of samples around 4 TU and 60 pMC indicates a multi-component system with mixtures of younger and older water fractions. Some of these samples (e.g. #26, #27, #28) are not visible in Fig. 4D as it displays only young water fractions.

Figure 4Selected synoptic plots from different environmental tracers using an EM (green), DM (orange), and PFM (blue) as proxies for the aquifer geometry. Groundwater samples are represented by a black point. (A) initial (3H +3He) tritium versus infiltration year, (B) tritium versus radiocarbon and springs shown as red points, (C) tritium versus tritiogenic helium and, (D) tritium versus sulphur hexafluoride. (E) shows versus signatures in sampled groundwater (black points). The green line displays an EM with numbers as mean residence times in years. The pink line shows the binary mixing model (BMM), indicating samples with mixed water fractions above the EM line. Tritiogenic helium as product of tritium decay is shown as a black dotted line and radiogenic helium as decay product of Thorium and Uranium is shown as a brown line. The solubility equilibrium line (red) is running from 0 °C (right end) to 50 °C (left end). (F) shows Ne versus 4He signatures, using the same red solubility equilibrium line as in panel (E) and the excess air line in light blue. Samples to the left below the red line indicate degassed samples. Note y axis break.

Figure 4C and D compare 3H with tritiogenic helium and SF6, respectively. Both tracer combinations indicate infiltration ranges of 4 to 38 years (Fig. 4C) and 12 to 34 years (Fig. 4D). Overall, the samples display low 3H concentrations, averaging 7.5 TU, which is characteristic of young European groundwater systems (Ying et al., 2024). Sample #27, being at the detection limit in tritium, seems to have had some tritium originally, since it shows some tritiogenic 3He, but this can also be a small dispersive admixture from the bomb peak. Inspecting the sample cluster #17, #18, #25, #29 of Fig. 4D shows high SF6 values, for which an air contamination is possible that is also found in Fig. 4C and F. Even though some samples show increased concentrations above 3 fMol L−1 SF6, they are still in a range that can be explained by atmospheric equilibrium with amounts of excess air uneven in Europe. No indication for underground production of SF6 was drawn, which is typical for young water (Harnisch and Eisenhauer, 1998; Friedrich et al., 2013).

Figure 4E and F show versus and Ne versus 4He signatures in sampled groundwater. All samples left below the red solubility equilibrium line (Fig. 4F) show degassing effects, while sample #13 shows significant contamination with air. The meeting point of all lines in plot 4E at of 4.4 and of corresponds to atmospheric equilibrium at 10 °C, while a ratio of for 3He to 4He is assumed for the terrigenic end-member (bottom left end of the brown line). Other infiltration temperatures correspond to the red solubility equilibrium line between 0 °C (right in Fig. 4E and up in Fig. 4F) and 50 °C (left in Fig. 4E and down in Fig. 4F). Older water fractions are situated in areas of low ratios and low ratios and follow the brown radiogenic helium line. The decay of tritium delivers only negligible amounts of helium but it is pure 3He and results in the vertical line of tritiogenic helium. The PFM with no mixture would follow the vertical line until all tritium decayed and then follow the radiogenic line of underground helium production. The EM, which is displayed only for comparison as a green line, then deviates from these two lines since there is always a mixture between very old and very young components in an EM. The pink line for the binary mixing model (BMM) connects a point of 50 TU decayed into 3He (top right) to the point of infinite age with radiogenic helium production (bottom left). Since all samples are located in the space opened up between the boundaries of the red solubility line, the black tritiogenic line, the brown radiogenic line and the pink BMM line in Fig. 4E, they can all be explained by mixed water fractions of recent water (containing tritiogenic helium) and old water (containing radiogenic helium). It turns out that helium is the most sensitive qualitative indicator for admixtures of an old component, although this component cannot be quantified without having the helium concentration in the old end member.

CFC-11 and CFC-12 were determined using the same method as SF6. The plot of CFC-11 versus CFC-12 (see Fig. S1 in the Supplement) shows that both species were degraded in the anaerobic sediments of the aquifers presented here. The results therefore do not provide reliable estimates of groundwater time scales and are not further discussed.

Figure 5Tritium-Helium age in years of sampled groundwater along a 450 km stretch of the Elbe River. For better spatial orientation: groundwater sampling locations which are located along the start of the studied Elbe section are represented by warm colours. Locations along the end are represented by cold colours. Base Map derived from QGIS desktop.

5.1 Stable isotopes

The δ18O and δ2H values of the sampled groundwater (Fig. 3A) indicate minimal evaporation. However, sample #28 shows a more pronounced evaporation of 8 %, which can be attributed to the influence of former gravel pit lakes in the recharge area, likely causing a heavier isotopic signature as lake water mixed with groundwater (Stichler et al., 2008). Similarly, sample #24 exhibits 4.2 % evaporation, resulting from infiltration through seasonally filled streams such as the former Ehle and Umflutehle (Benettin et al., 2018). The nitrate isotopes δ18O and δ15N in NO3 reveal strong enrichment but do not follow uniform enrichment trends (Fig. 3C, D). This heterogeneity can be explained by the diverse aquifer systems and groundwater bodies sampled, which are influenced by agricultural areas under variable land-use practices (Craswell, 2021). The isotopic signatures suggest that organic sources, such as soil organic matter and manure (Clark and Fritz, 2013), dominate the nitrate inputs in most samples. No synthetic fertiliser residues were detected, except in spring samples #1 and #3 within the Saxonian Cretaceous aquifer, which raises questions about potential contamination sources. Denitrification rates across the study area were generally low to moderate, with the highest rates observed in samples #7, #11, #12 and #20 (Fig. 3D). This partly limited denitrification activity could be attributed to the relatively young groundwater ages, which may not provide sufficient time for extensive denitrification processes to occur within the aquifers (Bourke et al., 2019). Similar observations of lower denitrification in young groundwater have been reported in other European studies (e.g., Rivett et al., 2008; Weyer et al., 2019). Eh values of the 2022 sampled groundwaters ranging from −236 to +315 mV, while samples from 2020 show higher values from −42 to +613 mV, indicating more oxidative conditions, making denitrification less likely.

Table 1Summary of calculated and modelled groundwater time scales from multiple tracers.

* Without outlier values >45 years.

The δ13C values of DIC in groundwater (Fig. 3B) reflect the interplay of biogeochemical processes such as root respiration, microbial activity, carbonate dissolution, and silicate weathering (Mook, 2005). In this study, δ13C values range from −23 ‰ V-PDB, characteristic of root respiration from C3 plants, to −12 ‰ V-PDB, typical of freshwater carbonate dissolution, highlighting the influence of both organic and inorganic carbon sources (Meier-Augenstein, 1999). Further, Clark and Fritz (2013) defined the groundwater δ13C range from −16 ‰ to −14 ‰ and manure signatures of C are described from −24 ‰ to −16 ‰ (Cravotta, 1997; Vitòria et al., 2004). Both ranges fit our measured δ13C values. In silicate-dominated aquifers, DIC levels tend to be lower due to the limited availability of carbonate material for dissolution (Appelo and Postma, 2005). Chemical weathering of silicates primarily releases cations and aqueous silica, contributing minimally to inorganic carbon, in contrast to carbonate-rich systems where calcite or dolomite dissolution dominates.

The δ13C values of infiltrating groundwater in agriculture dominated areas (blue points in Fig. 3B) are strongly influenced by soil-derived CO2 from root respiration and microbial decomposition of organic matter (Gat et al., 2001). Elevated microbial activity in such soils often correlates with higher denitrification rates (blue points in Fig. 3C), further affecting the isotopic composition of DIC. Lighter δ13C signatures are therefore typically affected by these agricultural processes and lead to isotopic enrichment (more positive values; Clark and Fritz, 2013). Another critical aspect are the residence times within the aquifer, as longer residence times in carbonate-rich aquifers lead to higher DIC concentrations and δ13C values closer to the signature of freshwater carbonate minerals. In contrast, younger groundwater from silicate-rich areas as in our study often shows lower DIC concentrations dominated by lighter soil CO2 signatures (Clark and Fritz, 2013). Mixing of waters from different flow paths further explains the variability in DIC levels and carbon isotopic composition.

The sampled springs yielded inconclusive results and were identified as outlier values for various parameters (shown representatively in Figs. 3A, C and 4B). Among others, this might be related to the inherent complexity of the hosting fractured aquifers, which represent a multicontinuum or at least dual porosity system possessing no uniform flow path but rather a dynamic mixture of slow and fast flow paths and accordingly widely spread residence times (Suckow and Gerber, 2022). To gain more valid insights into such aquifers, a time series of multi tracer (short to long term tracers) measurements and samples from the upstream source aquifers are necessary (Suckow, 2014).

5.2 Environmental age tracers

The finding that only two samples are at the detection limit of tritium is a clear and robust indication that the catchments investigated are dominated by young water infiltrated after the 1960s. This indication is the most robust, because tritium is a part of the water molecule itself and therefore not influenced by gas loss (CFCs, SF6, 3He) or geochemical processes (CFCs, 14C). Table 1 presents further indicative age estimates which are derived from Figs. 4 and 5. Although these estimates are approximations, they are in agreement with and refine the results of Wendland et al. (2004), who estimated the mean residence time in the Elbe catchment area to be 25 years using a stochastic model with large uncertainties. However, Esser (1980) underestimated the age distribution by stating that water fractions older than 10 years account for only a small proportion of about 5 %.

Although the majority of the samples exhibit “young ages”, several exceptions are noteworthy. Samples #12, #17, #19, and #27 display evidence of admixture with older, tritium-free waters, as they fall below the 3H line for precipitation (light blue, Fig. 4A). Further samples #18, #24, #27, #28 show admixtures of older water fractions according to their 14C values around 60 pMC (Fig. 4B) and more evident, according to their high 4He values for sample #12, #21, #25, #30 (Fig. 4E and F). These components must have infiltrated prior to the first nuclear tests in 1953, as 3H concentrations in precipitation have been significantly elevated since that time due to atmospheric nuclear testing (Schmidt et al., 2020). Additional samples (#06, #12, #14, #21, #25, #27, #30) also show clear admixtures of older waters according to vs. data in Fig. 4E. These fall to the left of the EM (green line, Fig. 4E) and the state of equilibrium (red line, Fig. 4E) and show correspondingly high radiogenic 4He, produced from the decay of U and Th in the aquifer. This suggests a mixing of old and young waters, as helium is the most robust indicator of old groundwater admixed to young water (IAEA, 2013).

Sample #19 exhibits an exceptionally high tritiogenic 3He value of 103 TU, significantly exceeding the average 3He concentration of 8 TU observed across the other samples, while maintaining a normal 3H concentration of 5.7 TU (Fig. 4). A plausible explanation would be that this is nearly unmixed water from around the thermonuclear bomb peak. Some samples (e.g. #7, #15, #21, #31, #32) exhibit 3H concentrations exceeding those of precipitation and thus the natural geogenic background (Fig. 4A, light blue line). This suggests these groundwater samples have been influenced by bank filtrate or influent conditions in general, as the Elbe River is highly enriched in 3H with 50–100 TU and more (Schubert et al., 2020; Zill et al., 2023). This is due to the cooling water release of the Czech nuclear power plant into the Moldau River (Hanslík et al., 2017), the largest tributary of the Elbe. Sampling wells close to the Elbe River and situated in the floodplain are therefore marked with an asterisk in Tables S1 and S2, suggesting higher 3H concentrations than the natural background.

Several samples (#15, #18, #26, #29, #35) display evidence of either geogenic degassing or degassing during sampling (see Fig. 4F, below the red solubility line). These degassing processes render the samples unsuitable for noble gas () analyses. A geogenic mechanism for noble gas degassing could involve nitrate reduction processes in nitrate-rich groundwater (e.g., #26 and #35 showing NO3 concentrations of 72 and 154 mg L−1, respectively), generating N2O or N2 bubbles. These bubbles equilibrate with dissolved noble gases, effectively partitioning them into the gas phase and reducing their concentrations in the groundwater (Kipfer et al., 2002). Sampling-related degassing may occur when air bubbles form due to de-pressurisation during sampling, leading to stripping of He and Ne. The 14C analysis of DIC confirms the young age of groundwater along the Elbe River (Fig. 4B). As values down to 60 pMC can be readily explained by geochemical interactions, only one sample (#1) shows an unequivocal indication of radioactive decay. All other measured 14C values in combination with tritium indicate recent recharge or geochemical interactions of the carbonate system. Additionally, the generally low radiogenic 4He concentrations observed in the samples are typical for young groundwater in Europe, which has limited time to accumulate helium from radiogenic sources (Broers et al., 2021; Desens et al., 2023).

Our study determined the time scales of groundwater flow in Cretaceous and Quaternary aquifers along a 450 km stretch of the German Elbe River. Using the environmental tracers , SF6, CFC's and 14C and a lumped parameter approach, flow times in the range of a few decades were derived. In general, this is a young mixed groundwater system that can react quickly to changes, while the admixture of older groundwater is detectable in smaller proportions, except for multi-component samples like #12, #18, #21, #27, #29, #30, #31. Spatially, this refers to river sections of stream km 150, 218, 280, 350–370 and 395. No valid statement could be made about the age of spring water in the mountainous upstream areas. Natural nitrate degradation is low to moderate with highest nutrient concentrations of NO3 and PO4 in samples #6, #8, #12, #26, #35 and #10, #32x, #34, respectively. In the coming decades, a reduction in groundwater-borne nutrient concentrations entering the Elbe River is anticipated. Consequently, the impact of groundwater discharge on riverine eutrophication is expected to be less significant in near-future scenarios. This information is crucial as it has been shown that groundwater can contribute significantly to riverine eutrophication in the Elbe, and therefore adapted management to mitigate algal blooms and protect aquatic ecosystems is valuable. In the future, the additional use of (i) the age tracer 39Ar would be beneficial, as it covers the age spectra between the tracers 3H and 14C used here and (ii) wells with filter screens less than 2 m should be preferentially sampled, as they result in minimally affected tritium-helium ages.

All data are given in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-29-6885-2025-supplement.

JZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft; ASu: Formal Analysis, Software, Methodology, Writing – original draft; UM: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft; JS: Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft. ASch: Formal analysis, Resources, Writing - original draft. CS: Project planning, Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Resources acquisition, Writing – original draft.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors are grateful to the Dept. of Catchment Hydrology for financially supporting the study and Ronald Krieg, Ralf Merz, Stefan Geyer and Kay Knöller for field assistance. We thank Silke Köhler, Gabriele Stams, Wolfgang Städter, Stoyanka Schumann, Gudrun Schäfer, Stephan Weise and Marion Martienssen for analytical support. We are extremely grateful to Georg Houben from the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources for covering part of the costs of the helium analyses.

This research was granted by Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt (DBU) through the scholarship to Julia Zill (grant no. 20019/637). The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the Research Centre of the Helmholtz Association through project DEAL. Parts of the analytical costs have been covered by the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, department of groundwater quality and protection.

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research – UFZ.

This paper was edited by Nunzio Romano and reviewed by Matthew Currell and one anonymous referee.

Ad-Hoc-AG Hydrogeologie: Regional Hydrogeology of Germany: Aquifers in Germany, their distribution and properties, Geol. Jb., A 163, 456, 2016.

Aeschbach-Hertig, W., Peeters, F., Beyerle, U., and Kipfer, R.: Interpretation of dissolved atmospheric noble gases in natural waters, Water Resources Research, 35, 2779–2792, 1999.

Appelo, C. A. J. and Postma, D.: Geochemistry, groundwater and pollution (rev. ed.): Rotterdam, Netherlands, CRCPress/Balkema, 536 p., 1996.

Benettin, P., Volkmann, T. H. M., von Freyberg, J., Frentress, J., Penna, D., Dawson, T. E., and Kirchner, J. W.: Effects of climatic seasonality on the isotopic composition of evaporating soil waters, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 2881–2890, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-2881-2018, 2018.

Bourke, S. A., Iwanyshyn, M., Kohn, J., and Hendry, M. J.: Sources and fate of nitrate in groundwater at agricultural operations overlying glacial sediments, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 23, 1355–1373, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-23-1355-2019, 2019.

Briggs, M. A. und Hare, D. K.: Explicit consideration of preferential groundwater discharges as surface water ecosystem control points, Hydrological Processes, 32, 2435–2440, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.13178, 2018.

Broers, H. P., Sültenfuß, J., Aeschbach, W., Kersting, A., Menkovich, A., de Weert, J., and Castelijns, J.: Paleoclimate signals and groundwater age distributions from 39 public water works in the Netherlands; insights from noble gases and carbon, hydrogen and oxygen isotope tracers, Water Resources Research, 57, e2020WR029058, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR029058, 2021.

Brookfield, A. E., Hansen, A. T., Sullivan, P. L., Czuba, J. A., Kirk, M. F., Li, L., Newcomer, M. E., and Wilkinson, G.: Predicting algal blooms: are we overlooking groundwater?, Science of the Total Environment, 769, 144442, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144442, 2021.

Busenberg, E. and Plummer, L. N.: Dating young groundwater with sulfur hexafluoride: Natural and anthropogenic sources of sulfur hexafluoride, Water Resources Research, 36, 3011–3030, 2000.

Busenberg, E. and Plummer, L. N.: Dating groundwater with trifluoromethyl sulfurpentafluoride (SF5CF3), sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), CF3Cl (CFC-13), and CF2Cl2 (CFC-12), Water Resources Research, 44, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007WR006150, 2008.

Chen, K., Tetzlaff, D., Goldhammer, T., Freymueller, J., Wu, S., Andrew Smith, A., Schmidt, A., Liu, G., Venohr, M., and Soulsby, C.: Synoptic water isotope surveys to understand the hydrology of large intensively managed catchments, Journal of Hydrology, 623, 129817 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129817, 2023.

Clark, I. D. and Fritz, P.: Environmental isotopes in hydrogeology, CRC press, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781482242911, 2013.

Cook, P. G. and Solomon, D. K.: Recent advances in dating young groundwater: chlorofluorocarbons, 3H3He and 85Kr, Journal of Hydrology, 191, 245–265, 1997.

Corcho Alvarado, J. A., Purtschert, R., Barbecot, F., Chabault, C., Rueedi, J., Schneider, V., Aeschbach-Hertig, W., Kipfer, R., and Loosli, H. H.: Constraining the age distribution of highly mixed groundwater using 39Ar: A multiple environmental tracer (3H/3He, 85Kr, 39Ar, and 14C) study in the semiconfined Fontainebleau Sands Aquifer (France), Water Resour. Res., 43, W03427, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006WR005096, 2007.

Craswell, E.: Fertilizers and nitrate pollution of surface and groundwater: an increasingly pervasive global problem, SN Applied Sciences, 3, 518, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-021-04521-8, 2021.

Cravotta III, C. A.: Use of stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfer to identify sources of nitrogen in surface waters in the Lower Susquehanna River basin, Pennsylvania (No. 94-510), US Geological Survey, 1995.

Dagan, G.: Statistical theory of groundwater flow and transport: Pore to laboratory, laboratory to formation, and formation to regional scale, Water Research, 22, 120S–134S, https://doi.org/10.1029/WR022i09Sp0120S, 1986.

Dagan, G. and Nguyen, V.: A comparison of travel time and concentration approaches to modeling transport by groundwater, Journal of contaminant hydrology, 4, 79–91, 1989.

Daughney, C. J., Morgenstern, U., van Der Raaij, R., and Reeves, R. R.: Discriminant analysis for estimation of groundwater age from hydrochemistry and well construction: application to New Zealand aquifers, Hydrogeology Journal, 18, 417, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-009-0479-2, 2010.

Desens, A., Houben, G., Sültenfuß, J., Post, V., and Massmann, G.: Distribution of tritium-helium groundwater ages in a large Cenozoic sedimentary basin (North German Plain), Hydrogeology Journal, 31, 621–640, 2023.

Dodds, W. K.: Eutrophication and trophic state in rivers and streams, Limnology and Oceanography, 51, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2006.51.1_part_2.0671, 2006.

Eissmann, L.: Quaternary geology of eastern Germany (Saxony, Saxon–Anhalt, South Brandenburg, Thüringia), type area of the Elsterian and Saalian Stages in Europe, Quaternary Science Reviews, 21, 1275–1346, 2002.

Eriksson, E.: Compartment models and reservoir theory, Annual review of Ecology and Systematics, 67–84 pp., 1971.

Esser, N.: Bombentritium Zeitverhalten seit 1963 im Abfluss mitteleuropäischer Flüsse und kleiner hydrologischer Systeme, Dissertation University of Heidelberg, Germany, 1980.

Esser, N.: Tritium from bombs – the time behaviour since 1963 in mean-European rivers and smaller hydrological systems, Dissertation, Heidelberg Univ., Germany, 1980.

Friedrich, R., Vero, G., Von Rohden, C., Lessmann, B., Kipfer, R., and Aeschbach-Hertig: Factors controlling terrigenic SF6 in young groundwater of the Odenwald region (Germany), Applied Geochemistry, 33, 318–329, 2013.

Gat, J. R., Mook, W. G., and Meijer, H. A.: Environmental isotopes in the hydrological cycle, Principles and Applications UNESCO/IAEA Series, 2, 63–67, 2001.

Geyh, M. A.: Carbon-14 concentration of lime in soils and aspects of the carbon-14 dating of groundwater, IAEA, Isotope hydrology, 215–222, ISSN 0074-1884, 1970.

Gilmore, T. E., Genereux, D. P., Solomon, D. K., and Solder, J. E.: Groundwater transit time distribution and mean from streambed sampling in an agricultural coastal plain watershed, North Carolina, USA, Water Resources Research, 52, 2025–2044, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015WR017600, 2016.

Godwin, H.: Radiocarbon dating: fifth international conference, Nature, 195, 943–945, 1962.

Han, L. F. and Maloszewski, P.: Comment on LUMPED: a Visual Basic code of lumped-parameter models for mean residence time analyses of groundwater systems by Ozyurt and Bayari, Computers and Geosciences, 32, 708–712, 2006.

Hanslík, E., Marešová, D., Juranová, E., and Sedlářová, B.: Comparison of balance of tritium activity in waste water from nuclear power plants and at selected monitoring sites in the Vltava River, Elbe River and Jihlava (Dyje) River catchments in the Czech Republic, Journal of Environmental Management, 203, 1137–1142, 2017.

Hardenbicker, P., Weitere, M., Ritz, S., Schöll, F., and Fischer, H.: Longitudinal plankton dynamics in the Rivers Rhine and Elbe, River Research Applications, 32, 1264–1278, https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.2977, 2016.

Harnisch, J. and Eisenhauer, A.: Natural CF4 and SF6 on Earth, Geophysical Research Letters, 25, 2401–2404, 1998.

IAEA: Statistical treatment of data on environmental isotopes in precipitation, Technical Reports Series Nr. 331, International Atomic Energy Agency, 1992.

IAEA: Use of Chlorofluorocarbons in Hydrology. A Guidebook, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, 2006.

IAEA: Isotope Methods for Dating Old Groundwater, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, 2013.

IKSE: International Commission for the Protection of the Elbe, The Elbe and its catchment area. A geographical-hydrological and water management overview, Magdeburg, https://www.ikse-mkol.org/publikationen (last access: 22 July 2025), 2005.

Isokangas, E., Rossi, P. M., Ronkanen, A. K., Marttila, H., Rozanski, K., and Kløve, B.: Quantifying spatial groundwater dependence in peatlands through a distributed isotope mass balance approach, Water Resources Research, 53, 2524–2541, 2017.

Iverach, C. P., Cendón, D. I., Meredith, K. T., Wilcken, K. M., Hankin, S. I., Andersen, M. S., and Kelly, B. F. J.: A multi-tracer approach to constraining artesian groundwater discharge into an alluvial aquifer, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 5953–5969, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-5953-2017, 2017.

Kagabu, M., Matsunaga, M., Ide, K., Momoshima, N., and Shimada, J.: Groundwater age determination using 85Kr and multiple age tracers (SF6, CFCs, and 3H) to elucidate regional groundwater flow systems, Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 12, 165–180, 2017.

Kamjunke, N., Brix, H., Flöser, G., Bussmann, I., Schütze, C., Achterberg, E. P., Ködel, U., Fischer, P., Rewrie, L., Sanders, T., Borchardt, D., and Weitere, M.: Large-scale nutrient and carbon dynamics along the river-estuary-ocean continuum, Science of the Total Environment, 890, 164421, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164421, 2023.

Kipfer, R., Aeschbach-Hertig, W., Peeters, F., and Stute, M.: Noble gases in lakes and ground waters, University of Konstanz, 2002.

Kunkel, R. and Wendland, F.: Diffuse Nitrateinträge in die Grund-und Oberflächengewässer von Rhein und Ems: Ist-Zustands-und Maßnahmenanalysen (No. PreJuSER-55338), Programmgruppe Systemforschung und Technologische Entwicklung, 2006.

Lautz, L. K., Ledford, S. H., and Beltran, J.: Legacy effects of cemeteries on groundwater quality and nitrate loads to a headwater stream, Environmental Research Letters, 15, 125012, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abc914, 2020.

Levin, I. and Kromer, B.: Twenty years of atmospheric 14CO2 observations at Schauinsland station, Germany, Radiocarbon, 39, 205–218, 1997.

Małoszewski, P. and Zuber, A.: Determining the turnover time of groundwater systems with the aid of environmental tracers: 1. Models and their applicability, Journal of Hydrology, 57, 207–231, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(82)90147-0, 1982.

Maloszewski, P. and Zuber, A.: Influence of matrix diffusion and exchange reactions on radiocarbon ages in fissured carbonate aquifers, Water Resources Research, 27, 1937–1945, 1991.

Maloszewski, P. and Zuber, A.: Lumped parameter models for the interpretation of environmental tracer data, Report Number: IAEA-TECDOC-910, 1996.

Martin, S. L., Hayes, D. B., Kendall, A. D., and Hyndman, D. W.: The land-use legacy effect: Towards a mechanistic understanding of time-lagged water quality responses to land use/cover, Science of The Total Environment, 579, 1794–1803, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.158, 2017.

Martin, S. L., Hamlin, Q. F., Kendall, A. D., Wan, L., and Hyndman, D. W.: The land use legacy effect: looking back to see a path forward to improve management, Environmental Research Letters, 16, 035005, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abe14c, 2021.

Matsumoto, T., Chen, Z., Wei, W., Yang, G. M., Hu, S. M., and Zhang, X.: Application of combined 81Kr and 4He chronometers to the dating of old groundwater in a tectonically active region of the North China Plain, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 493, 208–217, 2018.

Mayer, A., Sültenfuß, J., Travi, Y., Rebeix, R., Purtschert, R., Claude, C., Le Gal La Salle, C., Miche, H., and Conchetto, E.: A multi-tracer study of groundwater origin and transit-time in the aquifers of the Venice region (Italy), Applied Geochemistry, 50, 177–198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2013.10.009, 2014.

Meier-Augenstein, W.: Applied gas chromatography coupled to isotope ratio mass spectrometry, Journal of Chromatography A, 842, 351–371, 1999.

McCallum, J. L., Engdahl, N. B., Ginn, T. R., and Cook, P. G.: Nonparametric estimation of groundwater residence time distributions: What can environmental tracer data tell us about groundwater residence time?, Water Resource Research, 50, 2022–2038, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR014974, 2014.

Molson, J. W. and Frind, E. O.: On the use of mean groundwater age, life expectancy and capture probability for defining aquifer vulnerability and time-of-travel zones for source water protection, Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 127, 76–87, 2012.

Mook, W. G.: Introduction to isotope hydrology. Stable and radioactive isotopes of hydrogen, oxygen and carbon, Taylor and Francis Group, ISBN 9780415398053, 2005.

Mroczek, E. K.: Henry's Law constants and distribution coefficients of sulfur hexafluoride in water from 25 C to 230 C, Journal of Chemical and Engineering Data, 42, 116–119, 1997.

Okofo, L. B., Adonadaga, M. G., and Martienssen, M.: Groundwater age dating using multi-environmental tracers (SF6, CFC-11, CFC-12, δ18O, and δD) to investigate groundwater residence times and recharge processes in Northeastern Ghana, Journal of Hydrology, 610, 127821, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127821, 2022.

Pearson Jr., F. J. and White, D. E.: Carbon 14 ages and flow rates of water in Carrizo Sand, Atascosa County, Texas, Water Resources Research, 3, 251–261, 1967.

Pearson, G. W. and Qua, F.: High-precision 14C measurement of Irish oaks to show the natural 14C variations from AD 1840–5000 BC: A correction, in: Calibration 1993, edited by: Stuiver, M., Long, A., and Kra, R. S., Radiocarbon, 35, 105–123, 1993.

Plummer, L. N. and Glynn, P. D.: Radiocarbon Dating in Groundwater Systems, in: Isotope Methods for Dating Old Groundwater, 33–89, edited by: Suckow, A., Aggarwal, P. K., and Araguas-Araguas, L. J., International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, ISBN 978-92-0-137210-9, 2013.

Poreda, R. J., Cerling, T. E., and Salomon, D. K.: Tritium and helium isotopes as hydrologic tracers in a shallow unconfined aquifer, Journal of Hydrology, 103, 1–9, 1988.

Purtschert, R., Love, A. J., Jiang, W., Lu, Z. T., Yang, G. M., Fulton, S., Wohling, D., Shand, P., Aeschbach, W., Bröder, L., Müller, P., and Tosaki, Y.: Residence times of groundwater along a flow path in the Great Artesian Basin determined by 81Kr, 36Cl and 4He: Implications for palaeo hydrogeology, Science of the Total Environment, 859, 159886, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159886, 2023.

Rivett, M. O., Buss, S. R., Morgan, P., Smith, J. W., and Bemment, C. D.: Nitrate attenuation in groundwater: a review of biogeochemical controlling processes, Water research, 42, 4215–4232, 2008.

Sanford, W.: Calibration of models using groundwater age, Hydrogeology Journal, 19, 13–16, 2011.

Sanford, W. E. and Pope, J. P.: Quantifying groundwater's role in delaying improvements to Chesapeake Bay water quality, Environmental Science and Technology, 47, 13330–13338, https://doi.org/10.1021/es401334k, 2013.

Schilling, O. S., Cook, P. G., and Brunner, P.: Beyond classical observations in hydrogeology: The advantages of including exchange flux, temperature, tracer concentration, residence time, and soil moisture observations in groundwater model calibration, Reviews of Geophysics, 57, 146–182, 2019.

Schlosser, P. and Winckler, G.: Noble gases in ocean waters and sediments, Reviews in mineralogy and geochemistry, 47, 701–730, 2002.

Schlosser, P., Stute, M., Dörr, H., Sonntag, C., and Münnich, K. O.: Tritium/3He dating of shallow groundwater, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 89, 353–362, 1988.

Schmidt, A., Frank, G., Stichler, W., Duester, L., Steinkopff, T., and Stumpp, C.: Overview of tritium records from precipitation and surface waters in Germany, Hydrological Processes, 4, 1489–1493, 2020.

Schubert, M., Siebert, C., Knoeller, K., Roediger, T., Schmidt, A., and Gilfedder, B.: Investigating groundwater discharge into a major river under low flow conditions based on a radon mass balance supported by tritium data, Water, 12, 2838, https://doi.org/10.3390/w12102838, 2020.

Shishaye, H. A., Tait, D. R., Maher, D. T., Befus, K. M., Erler, D., Jeffrey, L., Reading, M. J., Morgenstern, U., Kaserzon, S., Mueller, J., and De Verelle-Hill, W.: The legacy and drivers of groundwater nutrients and pesticides in an agriculturally impacted Quaternary aquifer system, Science of the Total Environment, 753, 142010, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.20242010, 2021.

Sigman, D. M., Casciotti, K. L., Andreani, M., Barford, C., Galanter, M. B. J. K., and Böhlke, J. K.: A bacterial method for the nitrogen isotopic analysis of nitrate in seawater and freshwater, Analytical Chemistry, 73, 4145–4153, 2001.

Stichler, W., Maloszewski, P., Bertleff, B., and Watzel, R.: Use of environmental isotopes to define the capture zone of a drinking water supply situated near a dredge lake, Journal of Hydrology, 362, 220–233, 2008.

Suckow, A.: Lumpy – an interactive lumped parameter modeling code based on MS access and MS excel, in: Proceedings of European Geosciences Union Congress, vol. 12, p. 2763, 2012.

Suckow, A.: The age of groundwater–Definitions, models and why we do not need this term, Applied Geochemistry, 50, 222–230, 2014.

Suckow, A. and Dumke, I.: A database system for geochemical, isotope hydrological, and geochronological laboratories, Radiocarbon, 43, 325–337, 2001.

Suckow, A. and Gerber, C.: Environmental Tracers to Study the Origin and Timescales of Spring Waters, Threats to Springs in a Changing World: Science and Policies for Protection, 85–109, edited by: Currell, M. J. and Katz, B. G., Geophysical Monograph Series, AGU, Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119818625.ch7, 2022.

Sültenfuß, J. and Massmann, G.: Dating with the 3 He-tritium-method: an example of bank filtration in the Oderbruch region, Grundwasser, 9, 221–234, 2004.

Sültenfuß, J., Roether, W., and Rhein, M.: The Bremen mass spectrometric facility for the measurement of helium isotopes, neon, and tritium in water, Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies, 45, 83–95, 2009.

Trettin, R., Gläßer, W., Lerche, I., Seelig, U., and Treutler, H. C.: Flooding of lignite mines: isotope variations and processes in a system influenced by saline groundwater, Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies, 42, 159–179, 2006.

UBA: Federal Environment Agency 2022, The Water Framework Directive – Waters in Germany 2021, Progress and challenges, Bonn, Dessau, https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1410/publikationen/221010_uba_fb_wasserrichtlinie_bf.pdf (last access: 9 September 2024), 2022.

Unterweger, M. P. and Lucas, L. L.: Calibration of the National Institute of Standards and Technology tritiated-water standards, Applied Radiation and Isotopes, 52, 527–531, 2000.

van der Grift, B., Broers, H. P., Berendrecht, W., Rozemeijer, J., Osté, L., and Griffioen, J.: High-frequency monitoring reveals nutrient sources and transport processes in an agriculture-dominated lowland water system, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 20, 1851–1868, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-20-1851-2016, 2016.

Vogel, J. C.: Carbon-14 dating of groundwater, Isotope hydrology, 1970, 225–236, 1970.

Wang, S., Hrachowitz, M., Schoups, G., and Stumpp, C.: Stable water isotopes and tritium tracers tell the same tale: no evidence for underestimation of catchment transit times inferred by stable isotopes in StorAge Selection (SAS)-function models, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 27, 3083–3114, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-27-3083-2023, 2023.

Wendland, F., Kunkel, R., Voigt, H. J. : Assessment of groundwater residence times in the pore aquifers of the River Elbe Basin, Environmental Geology, 46, 1–9, 2004.

Weyer, C.: Tracing biogeochemical processes and anthropogenic impacts in granitic catchments: temporal and spatial patterns and implications for material turnover and solute export (Doctoral dissertation), Bayreuth, 2019.

Wigley, T., M. L., Plummer, L. N., and Pearson Jr, F. J.: Mass transfer and carbon isotope evolution in natural water systems, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 42, 1117–1139, 1978.

Wilmsen, M. and Niebuhr, B.: Die Kreide in Sachsen, 3–12, in: Kreide-Fossilien in Sachsen, Teil 1, edited by: Niebuhr, B. and Wilmsen, M., Geologica Saxonica, Dresden, 60, ISBN 978-3-910006-53-9, 2014.

Wilske, C., Suckow, A., Mallast, U., Meier, C., Merchel, S., Merkel, B., Pavetich, S., Rödiger, T., Rugel, G., Sachse, A., Weise, S. M., and Siebert, C.: A multi-environmental tracer study to determine groundwater residence times and recharge in a structurally complex multi-aquifer system, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 24, 249–267, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-24-249-2020, 2020.

Ying, Z., Tetzlaff, D., Freymueller, J., Comte, J. C., Goldhammer, T., Schmidt, A., and Soulsby, C.: Developing a conceptual model of groundwater–Surface water interactions in a drought sensitive lowland catchment using multi-proxy data, Journal of Hydrology, 628, 130550, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130550, 2024.

Zill, J., Siebert, C., Rödiger, T., Schmidt, A., Gilfedder, B. S., Frei, S., Schubert, M., Weitere, M., and Mallast, U.: A way to determine groundwater contributions to large river systems: The Elbe River during drought conditions, Journal of Hydrology, 50, 101595, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2023.101595, 2023.

Zill, J., Perujo, N., Fink, P., Mallast, U., Siebert, C., and Weitere, M.: Contribution of groundwater-borne nutrients to eutrophication potential and the share of benthic algae in a large lowland river, Science of the Total Environment, 951, 175617, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175617, 2024.