the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Exploring hydrologic post-processing of ensemble streamflow forecasts based on affine kernel dressing and non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II

Jing Xu

François Anctil

Marie-Amélie Boucher

Forecast uncertainties are unfortunately inevitable when conducting a deterministic analysis of a dynamical system. The cascade of uncertainty originates from different components of the forecasting chain, such as the chaotic nature of the atmosphere, various initial conditions and boundaries, inappropriate conceptual hydrologic modeling, and the inconsistent stationarity assumption in a changing environment. Ensemble forecasting proves to be a powerful tool to represent error growth in the dynamical system and to capture the uncertainties associated with different sources. In practice, the proper interpretation of the predictive uncertainties and model outputs will also have a crucial impact on risk-based decisions. In this study, the performance of evolutionary multi-objective optimization (i.e., non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II – NSGA-II) as a hydrological ensemble post-processor was tested and compared with a conventional state-of-the-art post-processor, the affine kernel dressing (AKD). Those two methods are theoretically/technically distinct, yet share the same feature in that both of them relax the parametric assumption of the underlying distribution of the data (the streamflow ensemble forecast). Both NSGA-II and AKD post-processors showed efficiency and effectiveness in eliminating forecast biases and maintaining a proper dispersion with increasing forecasting horizons. In addition, the NSGA-II method demonstrated superiority in communicating trade-offs with end-users on which performance aspects to improve.

- Article

(2062 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2014 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Hydrologic forecasting is crucial for flood warning and mitigation (e.g., Shim and Fontane, 2002; Cheng and Chau, 2004), water supply operation and reservoir management (e.g., Datta and Burges, 1984; Coulibaly et al., 2000; Boucher et al., 2011), navigation, and other related activities. Sufficient risk awareness, enhanced disaster preparedness in the flood mitigation measures, and strengthened early warning systems are crucial in reducing the weather-related event losses. Hydrologic models are typically driven by dynamic meteorological models in order to issue forecasts over a medium-range horizon of 2 to 15 d (Cloke and Pappenberger, 2009). These kinds of coupled hydrometeorological forecasting systems are used as effective tools to issue longer lead times. Inherent in the coupled hydrometeorological forecasting systems are some predictive uncertainties, which are inevitable given the limits of knowledge and available information (Ajami et al., 2007). In fact, those uncertainties occur all along the different steps of the hydrometeorological modeling chain (e.g., Liu and Gupta, 2007; Beven and Binley, 2014). These different sources of uncertainty are related to deficiencies in the meteorological forcing, misspecified hydrologic initial and boundary conditions, inherent hydrologic model structure errors, and biased estimated parameters (e.g., Vrugt and Robinson, 2007; Ajami et al., 2007; Salamon and Feyen, 2010; Thiboult et al., 2016).

Many substantive theories have been proposed in order to quantify and reduce the different sources of cascading forecast uncertainties and to add good values to flood forecasting and warning. Among them, the superiority of ensemble forecasting systems in quantifying the propagation of predictive uncertainties (over deterministic systems) is now well established (e.g., Cloke and Pappenberger, 2009; Palmer, 2002; Seo et al., 2006; Velázquez et al., 2009; Abaza et al., 2013; Wetterhall et al., 2013; Madadgar et al., 2014). Numerous challenges have been well tackled; for example, (1) meteorological ensemble prediction systems (M-EPSs) (e.g., Palmer, 1993; Houtekamer et al., 1996; Toth and Kalnay, 1997) are refined and operated worldwide by the agencies such as the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), the National Center for Environmental Prediction (NCEP), the Meteorological Service of Canada (MSC) and more. (2) The forecast accuracy is highly improved by adopting higher-resolution data collection and assimilation. Sequential data assimilation techniques, such as the particle filter (e.g., Moradkhani et al., 2012; Thirel et al., 2013) and the ensemble Kalman filter (EnKF; e.g., Evensen , 1994; Reichle et al., 2002; Moradkhani et al, 2005; McMillan et al., 2013) provide an ensemble of possible re-initializations of the initial conditions, expressed in the hydrologic model as state variables such as soil moisture, groundwater level, and so on. (3) Forecasting skills of the coupled hydrometeorological forecasting systems are also improved by tracking predictive errors using the full uncertainty analysis. Multimodel schemes were proposed to increase performance and decipher the structural uncertainty (e.g., Duan et al., 2007; Fisher et al., 2008; Weigel et al., 2008; Najafi et al., 2011; Velázquez et al., 2011; Marty et al., 2015; Mockler et al., 2016). Thiboult et al. (2016) compared many hydrologic ensemble prediction systems (H-EPSs), accounting for the three main sources of uncertainties located along the hydrometeorological modeling chain. They pointed out that EnKF probabilistic data assimilation provided most of the dispersion for the early forecasting horizons but failed in maintaining its effectiveness with increasing lead times. A multimodel scheme allowed for sharper and more reliable ensemble predictions over a longer forecast horizon. (4) The statistical hydrologic post-processors, which have been added in the H-EPS for rectifying biases and dispersion errors (i.e., too narrow or too large) are numerous, as reviewed by Li et al. (2017). It is noteworthy that many hydrologic variables, such as discharge, follow a skewed distribution (i.e., low probability associated to the highest streamflow values), which complicates the task. Usually, in a hydrologic ensemble prediction system (H-EPS) framework (e.g., Schaake et al., 2007; Cloke and Pappenberger, 2009; Velázquez et al., 2009; Boucher et al., 2012; Abaza et al., 2017), the post-processing procedure over the atmospheric input ensemble is often referred to as pre-processing. By correcting the bias and adjusting the dispersion based on a comparison with past observations, statistical post-processing generally leads to a more accurate and reliable hydrologic ensemble forecast.

However, another challenge still remains, namely how to improve the human interpretation of probabilistic forecasts and the communication of integrated ensemble forecast products to end-users (e.g., operational hydrologists, water managers, local conservation authorities, stakeholders and other relevant decision-makers). Buizza et al. (2007) emphasized that both functional and technical qualities are supposed to be assessed for evaluating the overall forecast value of hydrological forecasts. Ramos et al. (2010) further note that the best way to communicate probabilistic forecast and interpret its usefulness should be in harmony with the goals of the forecasting system and the specific needs of end-users. Ramos et al. (2010) reported similar achievements from two studies obtained from a role play game and another survey during a workshop (Thielen et al., 2005). During the workshop, they explored the users' risk perception of forecasting uncertainties and how they dealt with uncertain forecasts for decision-making. The results revealed that there is still space for enhancing the forecasters' knowledge and experience on bridging the communication gap between predictive uncertainties quantification and effective decision-making.

Hence, in practice, which forecast quality impacts a given decision the most? Different end-users share their unique requirements. Crochemore et al. (2017) produced the seasonal streamflow forecasting by conditioning climatology with precipitations indices (SPI3 – standardized precipitation index over 3 months). Forecast reliability, sharpness (i.e., the ensemble spread), overall performance, and low-flow event detection were verified to assess the conditioning impact. In some cases, the reliability and sharpness could be improved simultaneously, while, more often, there was a trade-off between them.

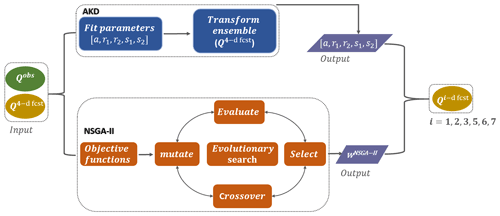

Here, two hydrological post-processors, namely the affine kernel dressing (AKD) and the evolutionary multi-objective optimization (non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II – NSGA-II), were explored. Compared to conventional post-processing methods, such as AKD, NSGA-II opens up the opportunity of improving the forecast quality in harmony with the forecasting aims and the specific needs of end-users. Multiple objective functions (i.e., here, verifying scores) for evaluating the forecasting performances of the H-EPSs are selected to guide the optimization process. The mechanisms of these two statistical post-processing methods are completely different. However, they share one similarity from another perspective, which is that they can estimate the probability density directly from the data (i.e., ensemble forecast) without assuming any particular underlying distribution. As a more conventional method, Silverman (1986) first proposed the kernel density smoothing method to estimate the distribution from the data by centering a kernel function K that determines the shape of a probability distribution (i.e., kernel) fitted around every data point (i.e., ensemble members). The smooth kernel estimate is then the sum of those kernels. As for the choice of bandwidth h of each dressing kernel, Silverman's rule of thumb finds an optimal bandwidth h by assuming that the data are normally distributed. Improvements to the original idea were soon to follow. For instance, the improved Sheather–Jones (ISJ) algorithm is more suitable and robust with respect to multimodality (Wand and Jones, 1994). Roulston and Smith (2003) rely on the series of best forecasts (i.e., best member dressing) to compute the kernel bandwidth h. Wang and Bishop (2005) and Fortin et al. (2006) further improved the best member method. The latter advocated that the more extreme ensemble members are more likely to be the best member of raw, under-dispersive forecasts, while the central members tend to be more precise for the over-dispersive ensemble. They proposed the idea that different predictive weights should be set over each ensemble member, given each member's rank within the ensemble. Instead of standard dressing kernels that act on individual ensemble members, Bröcker and Smith (2008) proposed the AKD method by assuming an affine mapping between ensemble members and observation over the entire ensemble. They approximate the distribution of the observation given the ensemble.

Given the single-model H-EPSs studied here, the hydrologic ensemble is generated by activating the following two forecasting tools: the ensemble weather forecasts and the EnKF. Henceforth, enhancing the H-EPS forecasting skill by assigning different credibility to ensemble members becomes preferred rather than reducing the number of members. The post-processing techniques, like the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II), are now common (e.g., Liong et al., 2001; De Vos and Rientjes, 2007; Confesor and Whittaker, 2007). Such techniques are conceptually linked to the multi-objective parameter calibration of hydrologic models using Pareto approaches. Indeed, formulating a model structure or representing the hydrologic processes using a unique global optimal parameter set proves to be very subjective. Multiple optimal parameter sets exist with satisfying behavior, given the different conceptualizations, although they are not identical Beven and Binley (1992). For example, Brochero et al. (2013) utilized the Pareto fronts generated with NSGA-II for selecting the best ensemble from a hydrologic forecasting model with a pool of 800 streamflow predictors in order to reduce the H-EPS complexity. Here, the expected output of the NSGA-II method is a group of solutions, also known as Pareto front, that identify the trade-offs between different objectives, subject to the end-users' needs and requirements.

In this study, the daily streamflow ensemble forecasts issued from five single-model H-EPSs over the Gatineau River (province of Québec, Canada) are post-processed. Details about the study area, hydrologic models, and hydrometeorological data are described in Sect. 2. Section 3 explains the methodology and training strategy of AKD and NSGA-II methods in parallel with the scoring rules that evaluate the performance of the forecasts. Specific concepts associated with those scores are also introduced in this section. A predictive distribution estimation based on the five single-model H-EPS configurations, which lack accounting for the model structure uncertainty, is presented in Sect. 4. The comparison of both statistical post-processing methods in improving the forecasting quality and enhancing the uncertainty communication are discussed and analyzed as well. The conclusion follows in Sect. 5.

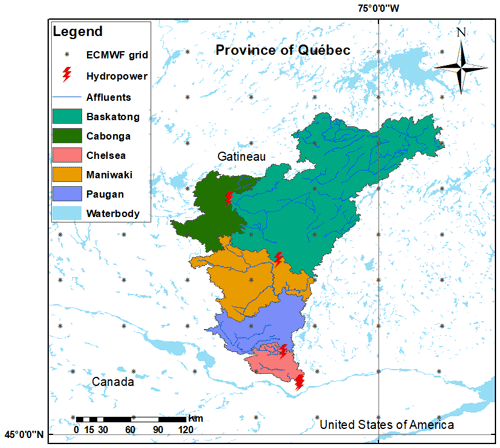

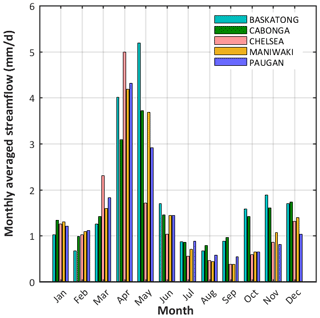

Figure 1 illustrates the study area, which is the Gatineau River located in the southern Québec province, Canada. It drains 23 838 km2 of the Outaouais and Montreal hydrographic region and experiences a humid continental climate. The river starts from Sugar Loaf Lake (47∘52–54 N, 75∘30–43 W) and joins the Ottawa River some 400 km later. The average daily temperature is about −3 ∘C in winter, while the temperature spectrum is 10–22 ∘C in summer (Kottek et al., 2006). The hydrologic regime of the study area is generally wet, cold, and snow covered. The largest flood typically appears in spring or early summer (i.e., from March to June) from snowmelt and rainfall. Autumnal rainfall often leads to a lesser peak between September and November (Fig. 2).

Figure 1The five sub-catchments of the Gatineau River. The red thunder strike symbols locate the dams, while the original ECMWF grid points, before downscaling, are marked using black asterisks.

Figure 2Hydrograph of the daily streamflow (millimeters per day; hereafter mm d−1) averaged over each month during 33 years from 1985 to 2017.

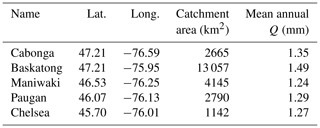

For operational hydrologic modeling, reservoir operation, and hydroelectricity production, the whole catchment has been divided up into the following five sub-catchments: Baskatong, Cabonga, Chelsea, Maniwaki, and Paugan (identified by different colors in Fig. 1). The sub-catchments are modeled independently from one another in order to inform a decision model operated by Hydro-Québec (e.g., Movahedinia, 2014). All hydroclimatic time series to the project were made available by Hydro-Québec, who carefully constructed them for their own hydropower operations. Dams are identified in Fig. 1 as red thunder strike symbols. The two uppermost ones allow for the existence of large headwater reservoirs, while the other three are run-of-the-river installations. The daily streamflow (in cubic meters per second; hereafter m3 s−1) time series entering the reservoirs were constructed by the electricity producer from a host of local information and made available to the study, along with spatially averaged minimum and maximum air temperature (degrees Celsius) and precipitation (millimeters) for each sub-basin. Table 1 summarizes the various hydroclimatic characteristics of the Gatineau River sub-catchments. Potential evapotranspiration is calculated from the temperature-based Oudin et al. (2005) formulation.

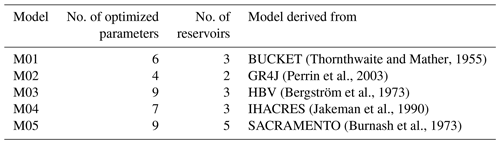

The HydrOlOgical Prediction LAboratory (HOOPLA; Thiboult et al., 2020, https://github.com/AntoineThiboult/HOOPLA) provides a modular framework to perform calibration, simulation, and streamflow prediction using multiple hydrologic models (up to 20 lumped models; Perrin, 2002; Seiller et al., 2012). The empirical two-parameter model, CemaNeige (Valéry et al., 2014), simulates snow accumulation and melt. In this study, five representative models were selected from HOOPLA as typical examples. Their main characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

(Thornthwaite and Mather, 1955)(Perrin et al., 2003)(Bergström et al., 1973)(Jakeman et al., 1990)(Burnash et al., 1973)Table 2Main characteristics of the hydrologic models (Seiller et al., 2012).

The original observational time series extends from January 1950 to December 2017, while, in terms of the input of HOOPLA, the observational period was limited to 33 years (1985–2017) to avoid the increased bias and variability caused by missing values within the record. The meteorological ensemble forecasts were retrieved from the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF; Fraley et al., 2010). The time series extends from January 2011 to December 2016. The meteorological ensemble forecast used the reduced Gaussian transformation for the latitude–longitude system during the THORPEX Interactive Grand Global Ensemble (TIGGE) database retrieving by using bilinear interpolation (e.g., Gaborit et al., 2013). The horizontal resolution was downscaled during the retrieval from the 0.5∘ ECMWF grid resolution to a 0.1∘ grid resolution. This study resorts to the 12:00 UTC (universal coordinated time) forecasts only, aggregated to a daily time step over a 7 d horizon. All data are aggregated at the catchment scale, averaging the grid points located within each sub-catchment. All of the time series were split in two, following the split-sample test (SST) procedure of Klemeš (1986), with 1986–2006 for calibration and 2013–2017 for validation. In both cases, 3 prior years were used for the spin-up period. January 2011–December 2016 is committed to hydrologic forecasting.

Initial condition uncertainties within each H-EPS are accounted for by a 100-member Ensemble Kalman Filter (EnKF) that adjusts the distribution function of the model states given observational distributions. Meteorological uncertainties are quantified by providing the 50-member ECMWF ensemble forcing to the H-EPSs. The resulting ensemble streamflow forecasts thus consist of 5000 members. This setup is similar to the one described in more details by Thiboult et al. (2016). The EnKF hyperparameters selection follows the work of Thiboult and Anctil (2015). Streamflow and precipitation uncertainties are assumed to be proportional; they are set to 10 % and 50 %, respectively. Temperature uncertainty is considered constant; it amounts to 2 ∘C. A Gaussian distribution describes the streamflow and temperature uncertainty, and a gamma law represents the precipitation uncertainty.

This study was conducted on the base of 1–7 d ensemble streamflow forecasts issued from five single-model H-EPSs and their realizations. Both AKD and NSGA-II methods are utilized in this study as the statistical post-processing or so-called ensemble interpretation method (Jewson, 2003; Gneiting et al., 2005) to transform the raw ensemble forecast into a probability distribution.

3.1 Affine kernel dressing (AKD)

Rather than adopting the ensemble mean and the standard deviation and approximate the distribution of the raw ensemble (Wilks, 2002), the principal insight of this methodology is that the probability distribution could be fitted of the observation when given the ensemble (Bröcker and Smith, 2008). The AKD method interprets the ensemble by approximating the distribution of the observation when given the ensemble forecasts. The ordering of the ensemble members is not taken into account (i.e., ensemble members are considered exchangeable here). Here, we denote the ensemble forecasts with m members over time t by and the observation by y(t). The mean and the variance of the raw ensemble forecasts are then as follows:

In a general form, the probability density function of defines the interpreted ensemble (i.e., kernel-dressed ensemble), given the original ensemble with free parameter vector θ, as follows:

for which the interpreted ensemble can be seen as a sum of probability functions (kernels) around each raw ensemble member. xi represents the ith ensemble member, and y is the corresponding observation. Hence, axi+b identifies the center of each kernel using the scale parameter a and offset parameter b. h is the positive bandwidth of each kernel. Note that various distributions could be adopted as kernels (Silverman, 1986; Roulston and Smith, 2003; Bröcker and Smith, 2008). We opted for the standard Gaussian density function with zero mean and unit variance for its computational convenience, as follows:

The mean and the variance of the interpreted ensemble can be defined as follows:

The mapping parameters of a, b, and h are determined from the raw ensemble. The updated mean μ′(X) of the kernel-dressed ensemble is a function of the raw ensemble mean μ(X), which is scaled and shifted using a and b. The variance υ′(X) of the kernel-dressed ensemble is a function of the initial ensemble variance υ(X), which is scaled and shifted using a2 and h2. Detailed derivations of these equations are given by Bröcker and Smith (2008).

AKD provides the solutions for determining the parameters of a, b, and h, which are determined as functions of X, as follows:

Here, hS is Silverman's factor (Silverman, 1986). Technically, we can use some scores (e.g., mean square error) to select the optimal bandwidth h for a kernel density estimation, yet this would be difficult to estimate for general kernels. Hence, the first rule of thumb proposed by Silverman gives the optimal bandwidth h which is the standard deviation of the distribution. And in this case, the kernel is also assumed to be Gaussian. The parameters are free parameters, and usually r1=0, r2=1, s1=0 and r2=1 are rational initial selections (Bröcker and Smith, 2008). Once the optimal free parameter vector is obtained, the interpreted ensemble can be set to the following:

where Zi is the resulting kernel-dressed ensemble based on the raw ensemble X and fitted parameters a, r1, and r2. Bröcker and Smith (2008) stressed that this AKD ensemble transformation works on the whole ensemble rather than on each individual member. Finally, the mean and variance of the interpreted ensemble shown in Eqs. (5) and (6) can be rewritten as follows:

3.2 Non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II)

Multi-objective optimization problems are common and typically lead to a set of optimal options (Pareto solution set) for users to choose from. Exploiting a genetic algorithm to find out all Pareto solutions from the entire solution space have been proposed and improved since the publication of the vector evaluated genetic algorithm (VEGA) around 1985 (Schaffer, 1985).

There exist two main standpoints for dealing with multi-objective optimization problems, namely to (1) define a new objective function as the weighted sum of all desired objective functions (e.g., MBGA, migrating-based genetic algorithm, and RWGA, random weighted genetic algorithm) or to (2) determine the Pareto set or its representative subsets for a selected group of objective functions (e.g., SPEA (strength Pareto evolutionary Algorithm), SPEA-II, NSGA, and NSGA-II). The first approach is more trivial as it reduces to a single-objective optimization problem. Yet, the needed weighting strategy is difficult to set accurately as a minor difference in weights may lead to quite different solutions. On the other hand, Pareto ranking approaches have been devised in order to avoid the problem of converging towards solutions that only behave well for one specific objective function. Users still have to select objective functions that are pertinent to the problem and that are not heavily correlated to one another. Readers may refer to the review by Konak et al. (2006) for more details.

Similar ideas can be utilized in this study, as the goal is to achieve a good forecast. Various efficiency criteria are needed when we verify whether an H-EPS is competent at issuing accurate and reliable forecasts. Accuracy might be the first idea that crosses our mind and indicates that there is a good match between the forecasts and the observations. Since here we are focused on probabilistic streamflow forecast, the accuracy could be measured by computing the distances between the forecast densities with the observations (Wilks, 2011). Usually, hydrologists could rely on the Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency criterion (NSE; Nash and Sutcliffe, 1970) for measuring how well forecasts can reproduce the observed time series. Transforming the time series beforehand allows one to specialize it (i.e., NSEinv, NSEsqrt) for specific needs (e.g., Seiller et al., 2017). NSE is dimensionless and varies on the interval of . NSE is attained by dividing the mean square error (MSE) by the variance of the observations and then subtracting that ratio from 1.

where xt and yt are the forecasted and observed values at time step t, respectively. and var(y) represent the mean and variance of the observations. A perfect model forecast output would have an NSE value that equals to one.

Meanwhile, bias, also known as systematic error, refers to the correspondence between the average forecast and the average observation, which is different from accuracy. For example, systematic bias exists in the streamflow forecasts that are consistently too high or too low. Hence, NSE and bias are utilized here as objective functions, which is to say that they are seeking to minimize the bias and maximize the NSE simultaneously. This brings us a multi-objective optimization question to solve.

Technically, inserting the elitism in the multi-objective optimization algorithms is not compulsory. However, it would have a strong influence if the algorithms could preserve the best individuals (i.e., elites) that were found during the search process and then incorporate the elitism back into the evolutionary process (Groşaelin et al., 2003). A classic, fast, and elitist multi-objective genetic algorithm, the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II; Deb et al., 2002) is adopted for searching for the Pareto solution set. NSGA-II offers three specific advantages over previous genetic algorithms. (1) There is no need to specify extra parameters such as the niche count for the fitness sharing procedure, (2) it reduces complexity over alternative GA implementations, and (3) elite individuals are well maintained, and hence, the effectiveness of the multi-objective genetic algorithm is largely improved.

In this study, the population is denoted by X(t). Specific steps for NSGA-II are briefly introduced here.

-

Layer the whole population by using the fast non-dominated sorting approach. i is initially set to 1, while zi represents the ith solution among the m ones. We compare the domination and non-domination relationship between the individuals zi and zj for all the , and i≠j. zi is the non-dominated solution as long as no zj dominates it. This process is repeated until all the non-dominated solutions are found and have composed the first non-dominated front of the population. Note that the selected individuals of the first front can be neglected when searching for subsequent fronts (i.e., marked as krank).

-

Find the crowding distance for each individual in each front. Deb et al. (2002) pointed out that the basic idea of the crowding distance calculated in the NSGA-II is “to find the Euclidian distance between each individual in a front based on their m objectives in the m-dimensional hyper space. The individuals in the boundary are always selected since they have infinite distance assignment. The large average crowding distance will result in better diversity in the population”. This step ensures the diversity of the population. For example, for the first front, sort the values of the objective functions in an ascending order. The boundary solutions (i.e., maximum and minimum solutions) are then the value at infinity. The crowding distance for other individuals can be assigned as follows:

where kdistance represents the value for the kth individual, and and are the values of the nth objective function at j+1 and j−1, separately. Thereafter, the crowding comparison operator can be utilized based on krank and kdistance. Individual zi will be assumed superior to zj if , or , when their Pareto front ranks are equal.

-

Elitism strategy is introduced in the main loop. Offspring population Qt is firstly generated from the parent population Pt after mutation and gene crossover. Then the abovementioned non-dominated sorting and crowding distance assignment are conducted on the composed population Rt that contain both Qt and Pt with the size of 2 m. The first-rate non-dominated solutions will be assign to the new parent population Pt+1. Outputs after the whole evolutionary search are the un-repeated non-domination solutions, and a weight matrix can also be extracted from the solutions. Specifically, in this study, the population size is set to 50, the number of objective functions equals to 2, the boundary is from 0 to 1, the mutation probability and crossover rate are 0.1 and 0.7, respectively, and the maximum evolution runs are 430 times.

3.3 Verifying metrics

The performance of the post-processed forecast distributions, mostly in terms of accuracy and reliability, is assessed using scoring rules. Except for bias and NSE described above, seven other verifying scores are applied to both the raw and post-processed forecast distributions.

The overall accuracy and reliability of the probabilistic forecast can be evaluated using the continuous ranked probability score (CRPS; Matheson and Winkler, 1976; Hersbach, 2000; Gneiting and Raftery, 2007). Hersbach (2000) decomposed the CRPS into two parts, i.e., reliability and resolution. In practice, The mean continuous ranked probability score (MCRPS) is the average value of CRPS over the whole time series T and is calculated using empirical distributions. Besides, MCRPS is negatively oriented, and the optimal MCRPS value is 0, as follows:

where y is the predictand, and represents the corresponding observations. is the cumulative distribution function of the forecasts at time step t. The Heaviside function H equals 0 (or 1) when (or ).

As for the deterministic metrics, we adopt the mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean squared error (RMSE; e.g., Brochero et al., 2013) to verify the average forecast error of the variable of interest. Both MAE and RMSE are negatively oriented and range from 0 to +∞. More accurate forecasts lead to lower MAE and RMSE. Note that the RMSE score tends to penalize the large errors more than MAE. In some cases, where the variance corresponding to the frequency distribution is higher, the RMSE will have larger increase while the MAE remains stable.

RMSE has the benefit of penalizing large errors more, so it can be more appropriate in some cases.

The Kling–Gupta efficiency (KGE; Gupta et al., 2009) also allows for a comprehensive performance assessment of the deterministic forecasts. KGE', a slightly modified version of KGE (Kling et al., 2012), avoids any cross-correlation between the bias and the variability ratios. It is defined as follows:

The correlation coefficient r represents the linear association between the deterministic forecast and the observations. μy(μo) and σy(σo) are the mean and the standard deviations of the forecasts (here it is the ensemble mean) and observation, respectively. CV is the dimensionless coefficient of variation.

The reliability diagram (Stanski et al., 1989) is a graphical representation of the reliability of an ensemble forecast. It contrasts the observed frequency against the probability of ensemble forecasts over all quantiles of interest. The proximity from the diagonal line indicates how closely the forecast probabilities are associated to the observed frequencies for selected quantiles. The 45∘ diagonal line thus represents perfect reliability, i.e., when the ensemble forecast probabilities equals the observation ones. When the plotted curve lies above the 45∘ line, the predictive ensemble is over-dispersed. It is otherwise under-dispersed. In addition, a flat curve represents that the forecast has no resolution (i.e., climatology).

The spread skill plot (SSP or later simply referred to as spread; Fortin et al., 2014) assesses the ensemble spread and identifies an ensemble forecast with poor predictive skill and large dispersion that would be positively assessed by a reliability diagram. Fortin et al. (2014) stresses that the ensemble spread should match the RMSE of the ensemble mean when the predictive ensemble is reliable. Thus, the SSP complements the spread component with an accuracy aspect.

3.4 Experimental setup

Establishing and analyzing both AKD and NSGA-II predictive models to interpret single-model hydrologic ensemble forecasts for uncertainty analysis can be summarized in three steps.

-

Determine the training period. Subject to the dataset used in this study, it can be considered to have two components, namely the observations/forecasts that last from January 2011 to December 2016 and the target ensemble for interpretation with a forecasting horizon that extends from day 1 to 7. Here, a common calibration/validation procedure was conducted on the second component of the dataset. We conducted the calibration on the day 4 forecast and then tested it on other lead times to assess the robustness of the predictive models. The skill of hydrologic forecasts fades away with increasing lead time. The 4 d ahead ensemble forecasts issued from each single-model H-EPSs and their corresponding observations are chosen as a training dataset, since they are located in the middle of the forecast horizon. The validation dataset then consists of the remaining forecasts, i.e., 1–3 and 5–7 d ahead raw forecasts issued from the associated H-EPSs. The procedure was selected as a specific example. Yet, one may decide otherwise, such as implementing the calibration/validation procedures separately for each day.

-

AKD mapping between the ensemble and observation over the training dataset. The observation time series are used to identify the free parameter vector , thereby minimizing the MCRPS to obtain the kernel-dressed ensemble. Note that AKD acts on the entire ensemble rather than on each individual member.

-

Evaluate the Pareto fronts (i.e., non-dominated solutions that minimize/maximize the bias and the NSE) and the weight matrix by applying NSGA-II over the training dataset. Sloughter et al. (2007) mentioned that the training period should be specific for each dataset or region. Here, a 30 d moving window is selected so that it contains enough training samples with coherent consistency, which is to say that the NSGA-II post-processors were trained using only the past 30 d and day 4 forecast data and then re-trained for every following day. From the operational perspective, a monthly moving window is especially more coherent and efficient in the real world, with a limited length for the time series.

A general flowchart of the streamflow input, AKD and NSGA-II frameworks, and expected outputs is illustrated in Fig. 3.

4.1 Ensemble member exchangeability

The issue of member interchangeability is central to this study, since, for AKD, each raw ensemble will be considered as a whole (i.e., indistinguishable members), whereas for NSGA-II a weight matrix is sought, which implies that different weights are assigned to each candidate members.

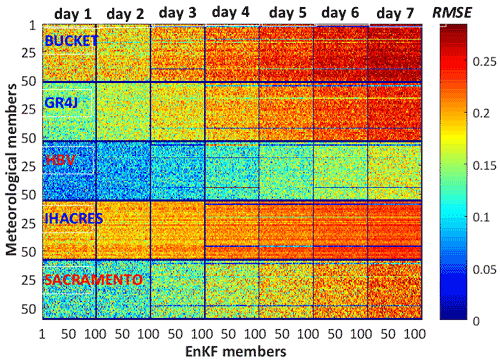

Interchangeability is here assessed visually, by simultaneously looking at the individual RMSE values of all 5000 members, seven daily forecast horizons, and five H-EPSs. Figure 4 displays the (typical) values for day 500 and Baskatong sub-catchment. The animation screenshots covering the different stages along the full time series are available in the Supplement. For each H-EPS forecast horizon box, horizontal lines consist of 100 EnKF members and vertical lines with 50 meteorological members. Mosaics with redder colors represent higher values of the RMSE. The decreasing predictive skill of the H-EPSs with lead time is, hence, shown as an increasingly red mosaic.

Figure 4Illustration of the RMSE values (mm d−1) of the individual members of the forecast issued by the five H-EPSs for the Baskatong sub-catchment on day 500. There are seven daily forecast horizons. Each box consists of 5000 members, including 100 EnKF members (horizontal lines) and 50 meteorological members (vertical lines).

Figure 4 displays the hydrologic forecasts built upon the 50-member ECMWF ensemble forecasts. The basic idea behind Fig. 4 (and its accompanying video) is to visually assess if the initial interchangeability of the weather forecasts holds for the hydrologic forecasts (i.e., horizontal lines), while the interchangeability of the probabilistic data assimilation scheme is assessed in parallel (vertical lines). One can notice that, in Fig. 4, colorful horizontal lines within each box start to appear from day 3 onwards, revealing a distinguishable character with longer lead times. At the same time, no obvious vertical lines are present in the same figure. These results suggest that the hydrologic forecasts produced in this study are fully interchangeable with respect to EnKF but less so with respect to the weather, with the latter being nonlinearly transformed by the hydrologic models. This opens up the possibility of assigning weights to the hydrologic forecasts associated to the ECMWF members.

For practical reasons, as the 100-member data assimilation ensemble was deemed to be fully interchangeable, this component is randomly reduced to 50 members from now on in this document. This procedure simplifies the implementation of the AKD and NSGA-II post-processing computations, the results of which are presented next.

4.2 NSGA-II convergence

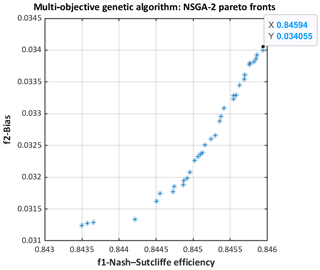

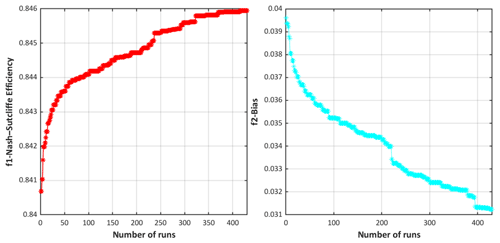

The NSGA-II Pareto front drawn in Fig. 5 (model M01 over the Baskatong catchment) is quite typical. In this multi-objective evolutionary search, 35 (non-dominated) Pareto solutions are identified. No objective can be improved more without the sacrifice of another. The optimal NSE is inevitably accompanied with the highest bias (e.g., NSE = 0.84594; bias = 0.034055) or vice versa. The solutions in the elbow region of the Pareto front are the compromise between both two objective functions. Pareto fronts with different numbers of solutions can be attained daily via setting the sliding window. Therefore, rather than choosing only one fixed position in the front, we opted to pick the solution randomly to respect and explore the diversity within. Figure 6 confirms the NSGA-II convergence.

Figure 5NSGA-II Pareto fronts of the model M01 over the Baskatong catchment. Horizontal and vertical axis are NSE and bias, separately.

Figure 6NSGA-II dynamical performance plots for both objective functions vs. the number of evaluations for model M01 over Baskatong catchment.

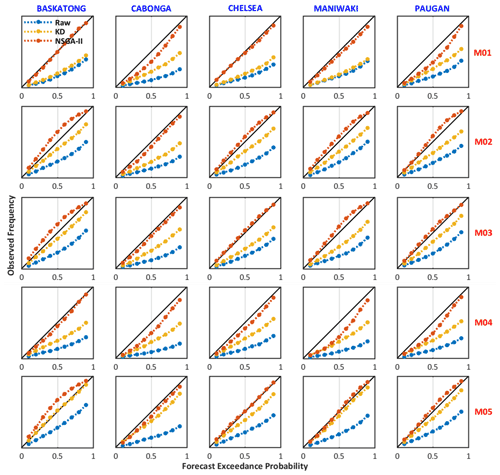

Figure 7Forecasting reliability of the raw, AKD, and NSGA-II forecasts on the calibration dataset (4 d ahead forecast) for five single-model H-EPSs over each individual catchment (January 2011–December 2016).

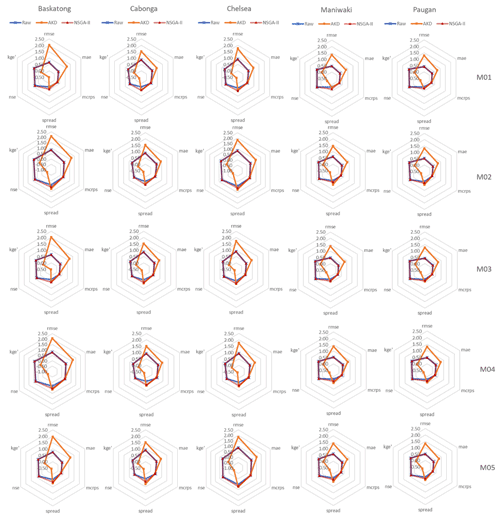

4.3 AKD and NSGA-II performance comparison

The reliability of the raw, kernel-dressed, and NSGA-II predictive distributions with different lead times are displayed in the reliability diagrams of Fig. 7. Both post-processing methods improve over the raw ensemble, especially the NSGA-II, as it achieves the best reliability. Over-dispersion exists mainly over the Baskatong catchments for NSGA-II.

The relevant accuracy performances of the raw, AKD, and NSGA-II predictive models are summarized using radar plots in Fig. 8. We can notice that the kernel-dressed ensemble fails in decreasing the forecast bias. However, it adjusts the ensemble dispersion properly. As for the NSGA-II, the post-processed ensemble has an obvious improvement on both bias and ensemble dispersion. Accordingly, it demonstrates a very reliable performance, as shown in the reliability diagram.

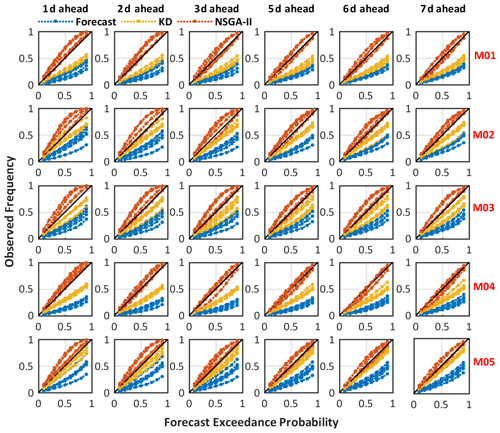

Figure 9Comparison of the reliability of the raw, kernel-dressed, and NSGA-II forecasts on the validation dataset (i.e., 1–3 and 5–7 d ahead forecasts) for five singe-model H-EPSs over all catchments (January 2011–December 2016).

The trained optimal free parameter vector or weight estimates are obtained over the 4 d ahead ensemble forecasts. They are then applied to the validation dataset. It comprises the 1, 3, 5, and 7 d ahead raw forecasts issued from the associated H-EPSs. Figure 9 shows the reliability diagrams for raw, kernel-dressed, and NSGA-II forecasts for the validation dataset over five individual catchments. Therefore, there are 15 lines shown in each sub-diagram. Again, raw forecasts (i.e., blue lines) display a severe under-dispersion, revealing that error growth is not maintained well in a single-model H-EPS. In general, the other two statistical post-processing methods succeed in improving the forecast reliability, with the curves closer to the bisector lines. The NSGA-II (i.e., red curves) especially demonstrates its superior ability for maintaining the reliability with the lead time. The over-dispersion appears with most of the AKD transformed ensembles (i.e., yellow lines), especially at shorter lead times. The ensemble spread tends to a proper level as the lead time increases. Note that there is one special case where the predictive distributions of the kernel-dressed ensemble are the most reliable for model M05 over almost all individual catchments.

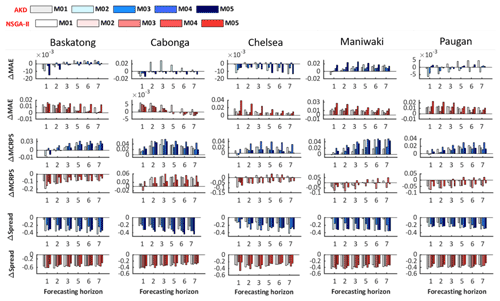

Figure 10Comparison of the MAE, MCRPS, and ensemble dispersion of the raw, AKD, and NSGA-II forecasts (i.e., 1–3 and 5–7 d ahead forecasts) for five singe-model H-EPSs over all catchments (January 2011–December 2016). The x axis for each sub-plot represents different horizons.

Figure 10 demonstrates the ensemble spread with different forecasting horizons on the x axis and shows the changing performance trend. Clearly, both the kernel-dressed ensemble and NSGA-II predictive forecasts have increased dispersion for all models over all catchments and result in more reliable predictive distributions. Figure 10 also provides an intuitive reference of the accuracy performance of the raw, AKD, and NSGA-II interpreted ensemble forecasts in terms of the MAE, MCRPS, and the ensemble dispersion for different forecasting horizons, showing the evolution of forecasting performance. Clearly, both the kernel-dressed ensemble and NSGA-II forecasts have increased dispersion compared to raw forecasts for all models and over all catchments. This results in more reliable predictive distributions, as shown in Fig. 9.

Hydrologic post-processing of streamflow forecasts plays an important role in correcting the overall representation of uncertainties in the final streamflow forecasts. Both the kernel ensemble dressing and the evolutionary multi-objective optimization approaches are tested in this study to estimate the probability density directly from the data (i.e., daily ensemble streamflow forecast) over five single-model hydrologic ensemble prediction systems (H-EPSs). The AKD method provides an affine mapping between the entire ensemble forecast and the observations without any assumption of the underlying distributions. The Pareto fronts generated with NSGA-II relax the parametric assumptions regarding the shape of the predictive distributions and offer trade-offs between different objectives in a multi-score framework.

The single-model H-EPSs explored in this study account for both forcing uncertainty and initial conditions uncertainty by using ensemble weather forecasts (ECMWF) and data assimilation (EnKF). Hydrologic post-processing with AKD and NSGA-II rely on very different assumptions and methodology. However, they both transform the raw ensembles into probability distributions. Results show that the post-processed forecasts achieve stronger predictive skill and better reliability than raw forecasts. In particular, the NSGA-II post-processed forecasts achieve the most reliable performances, since this method improves both bias and ensemble dispersion. However, over-dispersion may exist occasionally over the Baskatong catchment for NSGA-II. The kernel-dressed ensemble succeeds in adjusting the ensemble dispersion properly but bias increases. Note that, here, we calibrated the models on day 4 and then tested them on the other days to assess the robustness of the procedure. The results show that both AKD and NSGA-II predictive models could offer an efficient post-processing skill, and the procedure is quite robust as well. Others may try alternatives such as implementing the models separately on other lead times.

In the operational field, not only quantifying but also communicating the predictive uncertainties in probabilistic forecasts will become an essential topic. As mentioned in the introduction, another challenge that remains is how we can bridge the communication gap between the forecasters' and the end-users', such as the operational hydrologists, local conservation authorities, and some other relevant stakeholders, interpretation about probabilistic forecasts. What factor may have the strongest impact on decision-making? The different end-users may have their unique preferences and demands. For instance, the reliability and sharpness (i.e., spread) could be improved simultaneously, or there could be a trade-off between them.

In this paper, the performance of the NSGA-II method is compared with a conventional post-processing method, i.e., the AKD. NSGA-II demonstrated its superior ability in improving the forecast performance and communicating trade-offs with end-users on which performance aspects to improve most. As the selected objective functions here, neither NSE nor bias could be improved more without negatively impacting the other. The use of NSGA-II opens up opportunities to enhance the forecast quality in line with the specific needs of the end-users, since it allows for setting multiple specific objective functions from scratch. This flexibility should be considered as a key element for facilitating the implementation of H-EPSs in real-time operational forecasting.

Tools used in this study are open to the public. The scripts related to this article are available on GitHub (https://github.com/BaoMTL/hess; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6113443, Jing, 2022).

All the datasets used in this study are open to the public. The ensemble prediction system studied in this research was built from the HydrOlOgical Prediction LAboratory (HOOPLA), which is available on GitHub (https://github.com/AntoineThiboult/HOOPLA, Thiboult et al., 2019). ECMWF meteorological ensemble forecast data can be retrieved freely from the TIGGE data portal (https://apps.ecmwf.int/datasets/data/tigge/levtype=sfc/type=cf/, Bougeault et al., 2010). The observed datasets were provided by the Direction d'Expertise Hydrique du Québec and can be obtained on request for research purposes.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-26-1001-2022-supplement.

JX, FA, and MAB designed the theoretical formalism. JX performed the analytic calculations. Both FA and MAB supervised the project and contributed to the final version of the paper.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Funding for this work was provided by FloodNet, an NSERC Canadian Strategic Network, and by an NSERC Discovery Grant. We would like to thank Emixi Sthefany Valdez, who provided the ensemble forecast data that were used in this study. The authors also would like to thank the Direction d'Expertise Hydrique du Québec for providing hydrometeorological data and ECMWF for maintaining the TIGGE data portal and providing free access to archived meteorological ensemble forecasts. Moreover, we also appreciate all the reviewers' thoughtful and constructive comments, which significantly enhanced our research.

This research has been supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (grant nos. NETGP 451456-13 and RGPIN-2020-04286).

This paper was edited by Dimitri Solomatine and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Abaza, M., Anctil, F., Fortin, V., and Turcotte, R.: A comparison of the Canadian global and regional meteorological ensemble prediction systems for short-term hydrological forecasting, Mon. Weather Rev., 141, 3462–3476, https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-12-00206.1, 2013. a

Abaza, M., Anctil, F., Fortin, V., and Perreault, L.: Hydrological Evaluation of the Canadian Meteorological Ensemble Reforecast Product, Atmos. Ocean., 55, 195–211, https://doi.org/10.1080/07055900.2017.1341384, 2017. a

Ajami, N. K., Duan, Q., and Sorooshian, S.: An integrated hydrologic Bayesian multimodel combination framework: Confronting input, parameter, and model structural uncertainty in hydrologic prediction, Water. Resour. Res., 43, 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005WR004745, 2007. a, b

Bergström, S. and Forsman, A.: Development of a conceptual deterministic rainfall-runoff model, Nord. Hydrol., 4, 147–170, https://doi.org/10.2166/nh.1973.0012, 1973. a

Beven, K. and Binley, A.: GLUE: 20 years on, Hydrol. Process., 28, 5897–5918, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.10082, 2014. a

Beven, K. and Binley, A.: The future of distributed models: Model calibration and uncertainty prediction, Hydrol. Process., 6, 279–298, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.3360060305, 1992. a

Bougeault, P., Toth, Z., Bishop, C., Brown, B., Burridge, D., Chen, D. H., Ebert, B., Fuentes, M., Hamill, T. M., Mylne, K., Nicolau, J., Paccagnella, T., Park, Y.-Y., Parsons, D., Raoult, B., Schuster, D., Silva Dias, P., Swinbank, R., Takeuchi, Y., Tennant, W., Wilson, L., and Worley, S.: The THORPEX interactive grand global ensemble, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 91, 1059–1072, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010BAMS2853.1, 2010 (data available at: https://apps.ecmwf.int/datasets/data/tigge/levtype=sfc/type=cf/, last access: 6 February 2022). a

Buizza, R., Asensio, H., Balint, G., Bartholmes, J., Bliefernicht, J., Bogner, K., Chavaux, F., de Roo, A., Donnadille, J., Ducrocq, V., Edlund, C., Kotroni, V., Krahe, P., Kunz, M., Lacire, K., Lelay, M., Marsigli, C., Milelli, M., Montani, A., Pappenberger, F., Rabufetti, D., Ramos, M. -H., Ritter, B., Schipper, J, W., Steiner, P., J. Del Pozzo, T., and Vincendon, B.: EURORISK/PREVIEW report on the technical quality, functional quality and forecast value of meteorological and hydrological forecasts, ECMWF Technical Memorandum, ECMWF Research Department: Shinfield Park, Reading, United Kingdom, 516, 1–21, available at: http://www.ecmwf.int/publications/ (last access: 6 February 2022), 2007. a

Burnash, R. J. C., Ferral, R. L., and McGuire, R. A.: A generalized streamflow simulation system: conceptual modeling for digital computers, Technical Report, Joint Federal and State River Forecast Center, US National Weather Service and California Department of Water Resources, Sacramento, available at: https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=aQJDAAAAIAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR2&dq=A+generalized+streamflow+simulation+system:+conceptual+modeling+for+digital+computers,+Technical+Report,+Joint+Federal+and+State+River+Forecast+Center&ots=4tSaTg69cs&sig=sVb7nFZmMBgqy2p3oPmJYuztR6c&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false, (last access: 6 February 2022) 204 pp., 1973. a

Brochero, D., Gagné, C., and Anctil, F.: Evolutionary multiobjective optimization for selecting members of an ensemble streamflow forecasting model. Proceeding of the fifteenth annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation conference-GECCO, New York, United States, 6 July 2013, 13, 1221–1228, https://doi.org/10.1145/2463372.2463538, 2013. a, b

Bröcker, J. and Smith, L.A.: From ensemble forecasts to predictive distribution functions, Tellus A, 60, 663–678, 2008. a, b, c, d, e, f

Boucher, M.-A., Anctil, F., Perreault, L., and Tremblay, D.: A comparison between ensemble and deterministic hydrological forecasts in an operational context, Adv. Geosci., 29, 85–94, https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-29-85-2011, 2011. a

Boucher, M. A., Tremblay, D., Delorme, L., Perreault, L., and Anctil, F.: Hydro-economic assessment of hydrological forecasting systems, J. Hydrol., 416, 133–144, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.11.042, 2012. a

Cheng, C. T. and Chau, K. W.: Flood control management system for reservoirs, Environ. Modell. Softw., 19, 1141–1150, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2003.12.004, 2004. a

Cloke, H. L. and Pappenberger, F.: Ensemble flood forecasting: A review, J. Hydrol., 375, 613–626, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.06.005, 2009. a, b, c

ConfesorJr., R. B. and Whittaker, G. W.: Automatic Calibration of Hydrologic Models With Multi‐Objective Evolutionary Algorithm and Pareto Optimization 1, J. Am. Water Resour. As., 43, 981–989, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.2007.00080.x, 2007. a

Coulibaly, P., Anctil, F., and Bobée, B.: Daily reservoir inflow forecasting using artificial neural networks with stopped training approach, J. Hydrol., 230, 244–257, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(00)00214-6, 2000. a

Crochemore, L., Ramos, M.-H., Pappenberger, F., and Perrin, C.: Seasonal streamflow forecasting by conditioning climatology with precipitation indices, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 1573–1591, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-1573-2017, 2017. a

Datta, B. and Burges, S. J.: Short-term, single, multiple-purpose reservoir operation: importance of loss functions and forecast errors, Water. Resour. Res., 20, 1167–1176, https://doi.org/10.1029/WR020i009p01167, 1984. a

Deb, K., Pratap, A., Agarwal, S., and Meyarivan, T. A. M. T.: A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II, IEEE. T. Evolut. Comput., 6, 182–197, https://doi.org/10.1109/4235.996017, 2002. a, b

De Vos, N. J. and Rientjes, T. H. M.: Multi-objective performance comparison of an artificial neural network and a conceptual rainfall–runoff model, Hydrolog. Sci. J., 52, 397–413, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007WR006734, 2007. a

Duan, Q., Ajami, N. K., Gao, X., and Sorooshian, S.: Multi-model ensemble hydrologic prediction using Bayesian model averaging, Adv. Water. Resour., 30, 1371–1386, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2006.11.014, 2007. a

Evensen, G.: Inverse Methods and Data Assimilation in Nonlinear Ocean Models, Physica D, 77, 108–129, https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2789(94)90130-9, 1994. a

Fraley, C., Raftery, A. E., and Gneiting, T.: Calibrating Multimodel Forecast Ensembles with Exchangeable and Missing Members Using Bayesian Model Averaging, Mon. Weather Rev., 138, 190–202, https://doi.org/10.1175/2009MWR3046.1, 2010. a

Fisher, J. B., Tu, K. P., and Baldocchi, D. D.: Global estimates of the land-atmosphere water flux based on monthly AVHRR and ISLSCP-II data, validated at 16 FLUXNET sites, Remote Sens. Environ., 112, 901–919, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2007.06.025, 2008. a

Fortin, V., Favre, A. C., and Saïd, M.: Probabilistic forecasting from ensemble prediction systems: Improving upon the best-member method by using a different weight and dressing kernel for each member, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 132, 1349–1369, https://doi.org/10.1256/qj.05.167, 2006. a

Fortin, V., Abaza, M., Anctil, F., and Turcotte, R.: Why Should Ensemble Spread Match the RMSE of the Ensemble Mean?, J. Hydrometeorol., 15, 1708–1713, https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-14-0008.1, 2014. a, b

Gaborit, É., Anctil, F., Fortin V., and Pelletier, G.: On the reliability of spatially disaggregated global ensemble rainfall forecasts, Hydrol. Process., 27, 45–56, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9509, 2013. a

Gneiting, T. and Raftery, A. E.: Strictly proper scoring rules, prediction, and estimation, J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 102, 359–378. https://doi.org/10.1198/016214506000001437, 2007. a

Gneiting, T., Raftery, A., Westveld III, A. H., and Goldmann, T.: Calibrated probabilistic forecasting using ensemble model output statistics and minimum CRPS estimation, Mon. Weather Rev. 133, 1098–1118, https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR2904.1, 2005. a

Groşan, C., Mihai, O., and Mihaela, O.: The role of elitism in multiobjective optimization with evolutionary algorithms, Acta Univ. Apulensis Math. Inform., 83–90, available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265834177_The_role_of_elitism_in_multiobjective_optimization_with_evolutionary_algorithms (last access: 6 February 2022), 2003. a

Gupta, H. V., Kling, H., Yilmaz, K. K., and Martinez, G. F.: Decomposition of the mean squared error and NSE performance criteria: Implications for improving hydrological modeling, J. Hydrol., 377, 80–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.08.003, 2009. a

Hersbach, H.: Decomposition of the Continuous Ranked Probability Score for Ensemble Prediction Systems, Weather Forecast., 15, 559–570, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0434(2000)015<0559:DOTCRP>2.0.CO;2, 2000. a, b

Houtekamer, P. L., Lefaivre, L., Derome, J., and Ritchie, H.: A system simulation approach to ensemble prediction, Mon. Weater. Rev., 124, 1225–1242, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1996)124<1225:ASSATE>2.0.CO;2, 1996. a

Jakeman, A. J., Littlewood, I. G., and Whitehead, P. G.: Computation of the instantaneous unit hydrograph and identifiable component flows with application to two small upland catchments, J. Hydrol., 117, 275–300, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(90)90097-H, 1990. a

Jewson, S.: Comparing the ensemble mean and the ensemble standard deviation as inputs for probabilistic medium-range temperature forecasts, Cornell University, available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/physics/0310059.pdf (last access: 16 February 2022), 2003. a

Jing, X.: Code for hess-2020-238 (v1.0.1), Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6113443, 2022. a

Klemeš, V.: Operational testing of hydrological simulation models, Hydrolog. Sci. J., 31, 13–24, https://doi.org/10.1080/02626668609491024, 1986. a

Kling, H., Fuchs, M., and Paulin, M.: Runoff conditions in the upper Danube basin under an ensemble of climate change scenarios, J. Hydrol., 424, 264–277, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.01.011, 2012 a

Kulturel-Konak, S., Smith, A. E., and Norman, B. A.: Multi-objective search using a multinomial probability mass function, Eur. J. Oper. Res., 169, 918–931, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2004.08.026, 2006. a

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B., and Rubel, F.: World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated, Meteorol. Z., 15, 259–263, https://doi.org/10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130, 2006. a

Li, W., Duan, Q., Miao, C., Ye, A., Gong, W., and Di, Z.: A review on statistical postprocessing methods for hydrometeorological ensemble forecasting, Wires Water, 4, e1246, https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1246, 2017. a

Liong, S. Y., Khu, S. T. and Chan, W. T.: Derivation of Pareto front with genetic algorithm and neural network, J. Hydrol. Eng., 6, 52–61, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1084-0699(2001)6:1(52), 2001. a

Liu, Y. and Gupta, H. V.: Uncertainty in hydrologic modeling: Toward an integrated data assimilation framework, Water. Resour. Res., 43, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006WR005756, 2007. a

Madadgar, S., Moradkhani, H., and Garen, D.: Towards improved post-processing of hydrologic forecast ensembles, Hydrol. Process., 28, 104–122, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9562, 2014. a

Marty, R., Fortin, V., Kuswanto, H., Favre, A. C., and Parent, E.: Combining the bayesian processor of output with bayesian model averaging for reliable ensemble forecasting, J. R. Stat. Soc. C-Appl., 64, 75–92, https://doi.org/10.1111/rssc.12062, 2015. a

Matheson, J. E. and Winkler, R. L.: Scoring Rules for Continuous Probability Distributions, Manage. Sci., 22, 1087–1096, https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.22.10.1087, 1976. a

McMillan, H. K., Hreinsson, E. Ö., Clark, M. P., Singh, S. K., Zammit, C., and Uddstrom, M. J.: Operational hydrological data assimilation with the recursive ensemble Kalman filter, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 17, 21–38, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-21-2013, 2013. a

Mockler, E. M., O’Loughlin, F. E., and Bruen, M.: Understanding hydrological flow paths in conceptual catchment models using uncertainty and sensitivity analysis, Comput. Geosci., 90, 66–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2015.08.015, 2016. a

Moradkhani, H., Sorooshian, S., Gupta, H. V., and Houser, P. R.: Dual state-parameter estimation of hydrological models using ensemble Kalman filter, Adv. Water. Resour., 28, 135–147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2004.09.002, 2005. a

Moradkhani, H., Dechant, C. M., and Sorooshian, S.: Evolution of ensemble data assimilation for uncertainty quantification using the particle filter-Markov chain Monte Carlo method, Water Resour. Res., 48, 121–134, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012WR012144, 2012. a

Movahedinia, F.: Assessing hydro-climatic uncertainties on hydropower generation, Université Laval, Québec city, 7 pp., available at: https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/handle/20.500.11794/25294 (last access: 6 February 2022), 2014. a

Najafi, M. R., Moradkhani, H., and Jung, I. W.: Assessing the uncertainties of hydrologic model selection in climate change impact studies, Hydrol. Process., 25, 2814–2826, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.8043, 2011. a

Nash, J. E. and Sutcliffe, I.: River flow forecasting through conceptual models. Part 1 – A discussion of principles, J. Hydrol., 10, 282–290, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(70)90255-6, 1970. a

Oudin, L., Michel, C., and Anctil, F.: Which potential evapotranspiration input for a lumped rainfall-runoff model? Part 1 – Can rainfall-runoff models effectively handle detailed potential evapotranspiration inputs?, J. Hydrol., 303, 275–289, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2004.08.025, 2005. a

Palmer, T. N.: Extended-Range Atmospheric Prediction and the Lorenz Model, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 74, 49–65, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1993)074<0049:ERAPAT>2.0.CO;2, 1993. a

Palmer, T. N.: The economic value of ensemble forecasts as a tool for risk assessment: From days to decades, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 128, 747–774, https://doi.org/10.1256/0035900021643593, 2002. a

Ramos, M. H., Mathevet, T., Thielen, J., and Pappenberger, F.: Communicating uncertainty in hydro‐meteorological forecasts: mission impossible?, Meteorol. Appl., 17, 223–235, https://doi.org/10.1002/met.202, 2010. a, b

Perrin, C.: Vers une amélioration d'un modèle global pluie-débit au travers d'une approche comparative, Houille Blanche, 6–7, 84–91, https://doi.org/10.1051/lhb/2002089, 2002. a

Perrin, C., Michel, C., and Andréassian, V.: Improvement of a parsimonious model for streamflow simulation, J. Hydrol., 279, 275–289, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(03)00225-7, 2003. a

Reichle, R., McLaughlin, D. B., and Entekhabi, D.: Hydrologic data assimilation with the ensemble Kalman filter, Mon. Weather Rev., 130, 103–114, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(2002)130<0103:HDAWTE>2.0.CO;2, 2002. a

Roulston, M. S. and Smith, L. A.: Combining dynamical and statistical ensembles, Tellus A, 55, 16–30, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusa.v55i1.12082, 2003. a, b

Salamon, P. and Feyen, L.: Disentangling uncertainties in distributed hydrological modeling using multiplicative error models and sequential data assimilation, Water Resour. Res., 46, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009WR009022, 2010. a

Schaake, J., Demargne, J., Hartman, R., Mullusky, M., Welles, E., Wu, L., Herr, H., Fan, X., and Seo, D. J.: Precipitation and temperature ensemble forecasts from single-value forecasts, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., 4, 655–717, https://doi.org/10.5194/hessd-4-655-2007, 2007. a

Schaffer, J.: Multiple Objective Optimization with Vector Evaluated Genetic Algorithms, Proceedings of the First International Conference on Genetic Algortithms, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Inc., 93–100, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/216301392_Multiple_Objective_Optimization_with_Vector_Evaluated_Genetic_Algorithms (last access: 16 February 2022), 1985. a

Seiller, G., Anctil, F., and Perrin, C.: Multimodel evaluation of twenty lumped hydrological models under contrasted climate conditions, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 16, 1171–1189, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-16-1171-2012, 2012. a, b

Seiller, G., Roy, R., and Anctil, F.: Influence of three common calibration metrics on the diagnosis of climate change impacts on water resources, J. Hydrol., 547, 280–295, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2017.02.004, 2017. a

Seo, D.-J., Herr, H. D., and Schaake, J. C.: A statistical post-processor for accounting of hydrologic uncertainty in short-range ensemble streamflow prediction, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., 3, 1987–2035, https://doi.org/10.5194/hessd-3-1987-2006, 2006. a

Shim, K. C., Fontane, D. G., and Labadie, J. W.: Spatial Decision Support System for Integrated River Basin Flood Control, J. Water. Res. Pl.-ASCE, 128, 190–201, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(2002)128:3(190), 2002. a

Silverman, B. W.: Density estimation for statistics and data analysis, Published in Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability, CRC Press, Chapman and Hal, London, 26, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315140919, 1986. a, b, c

Sloughter, J. M. L., Raftery, A. E., Gneiting, T., and Fraley, C.: Probabilistic Quantitative Precipitation Forecasting Using Bayesian Model Averaging, Mon. Weather Rev., 135, 3209–3220, https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR3441.1, 2007. a

Stanski, H. R., Wilson, L. J., and Burrows, W. R.: Survey of common verification methods in meteorology, World Weather Watch Tech. Report 8, WMO/TD, 358, 114 pp., https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.26947.71208, 1989. a

Thiboult, A. and Anctil, F.: On the difficulty to optimally implement the Ensemble Kalman filter: An experiment based on many hydrological models and catchments, J. Hydrol., 529, 1147–1160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.09.036, 2015. a

Thiboult, A., Anctil, F., and Boucher, M.-A.: Accounting for three sources of uncertainty in ensemble hydrological forecasting, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 20, 1809–1825, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-20-1809-2016, 2016. a, b, c

Thiboult, A., Seiller, G., and Anctil, F.: HOOPLA, GitHub [code], available at: https://github.com/AntoineThiboult/HOOPLA (last access: 16 February 2022), 2019. a

Thiboult, A., Seiller, G., Poncelet, C., and Anctil, F.: The HOOPLA toolbox: a HydrOlOgical Prediction LAboratory to explore ensemble rainfall-runoff modeling, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-2020-6, 2020. a

Thielen, J., Ramos, M. H., Bartholmes, J., De Roo, A., Cloke, H., Pappenberger, F., and Demeritt, D.: Summary report of the 1st EFAS workshop on the use of Ensemble Prediction System in flood forecasting, European Report EUR, Ispra, 22118, available at: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/2610_EUR22118EN.pdf (last access: 16 February 2022), 2005. a

Thirel, G., Salamon, P., Burek, P., and Kalas, M.: Assimilation of MODIS snow cover area data in a distributed hydrological model using the particle filter, Remote. Sens., 5, 5825–5850, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs5115825, 2013. a

Thornthwaite, C. W. and Mather, J. R.: The water balance, Centerton, New Jersey: Drexel Institute of Technology, Laboratory of Climatology, 8, 1–104, available at: https://oregondigital.org/downloads/oregondigital:df70pr001 (last access: 16 February 2022), 1955. a

Toth, Z. and Kalnay, E.: Ensemble Forecasting at NCEP and the Breeding Method, Mon. Weather Rev., 125, 3297–3319, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1997)125<3297:EFANAT>2.0.CO;2, 1997. a

Valéry, A., Andréassian, V., and Perrin, C.: As simple as possible but not simpler: What is useful in a temperature-based snow-accounting routine? Part 2 – Sensitivity analysis of the Cemaneige snow accounting routine on 380 catchments, J. Hydrol., 517, 1176–1187, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.04.058, 2014. a

Velázquez, J. A., Anctil, F., Ramos, M. H., and Perrin, C.: Can a multi-model approach improve hydrological ensemble forecasting? A study on 29 French catchments using 16 hydrological model structures, Adv. Geosci., 29, 33–42, https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-29-33-2011, 2011. a

Velázquez, J. A., Petit, T., Lavoie, A., Boucher, M.-A., Turcotte, R., Fortin, V., and Anctil, F.: An evaluation of the Canadian global meteorological ensemble prediction system for short-term hydrological forecasting, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 13, 2221–2231, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-13-2221-2009, 2009. a, b

Vrugt, J. A. and Robinson, B. A.: Treatment of uncertainty using ensemble methods: Comparison of sequential data assimilation and Bayesian model averaging, Water Resour. Res., 43, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005WR004838, 2007. a

Wand, M. P. and Jones, M. C.: Kernel smoothing, Chapman & Hall/CRC Monographs on Statistics & Applied Probability, 60, 1–15, available at: http://matt-wand.utsacademics.info/webWJbook/KernelSmoothingSample.pdf (last access: 16 February 2022), 1994. a

Wang, X. and Bishop, C. H.: Improvement of ensemble reliability with a new dressing kernel, Applied Meteorology and Physical Oceanography 131, 965–986, https://doi.org/10.1256/qj.04.120, 2005. a

Weigel, A. P., Liniger, M., and Appenzeller, C.: Can multi-model combination really enhance the prediction skill of probabilistic ensemble forecasts?, Q. J. Roy. Meteorol. Soc., 134, 241–260, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.210, 2008. a

Wetterhall, F., Pappenberger, F., Alfieri, L., Cloke, H. L., Thielen-del Pozo, J., Balabanova, S., Daňhelka, J., Vogelbacher, A., Salamon, P., Carrasco, I., Cabrera-Tordera, A. J., Corzo-Toscano, M., Garcia-Padilla, M., Garcia-Sanchez, R. J., Ardilouze, C., Jurela, S., Terek, B., Csik, A., Casey, J., Stankūnavičius, G., Ceres, V., Sprokkereef, E., Stam, J., Anghel, E., Vladikovic, D., Alionte Eklund, C., Hjerdt, N., Djerv, H., Holmberg, F., Nilsson, J., Nyström, K., Sušnik, M., Hazlinger, M., and Holubecka, M.: HESS Opinions ”Forecaster priorities for improving probabilistic flood forecasts”, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 17, 4389–4399, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-4389-2013, 2013. a

Wilks, D. S.: Smoothing forecast ensembles with fitted probability distributions, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 128, 2821–2836, https://doi.org/10.1256/qj.01.215, 2002. a

Wilks, D. S.: On the Reliability of the Rank Histogram, Mon. Weather Rev., 139, 311–316, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010MWR3446.1, 2011. a