the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Dynamics of hydrological and geomorphological processes in evaporite karst at the eastern Dead Sea – a multidisciplinary study

Robert A. Watson

Eoghan P. Holohan

Rena Meyer

Ulrich Polom

Fernando M. Dos Santos

Xavier Comas

Hussam Alrshdan

Charlotte M. Krawczyk

Torsten Dahm

Karst groundwater systems are characterized by the presence of multiple porosity types. Of these, subsurface conduits that facilitate concentrated, heterogeneous flow are challenging to resolve geologically and geophysically. This is especially the case in evaporite karst systems, such as those present on the shores of the Dead Sea, where rapid geomorphological changes are linked to a fall in base level by over 35 m since 1967. Here we combine field observations, remote-sensing analysis, and multiple geophysical surveying methods (shear wave reflection seismics, electrical resistivity tomography, ERT, self-potential, SP, and ground-penetrating radar, GPR) to investigate the nature of subsurface groundwater flow and its interaction with hypersaline Dead Sea water on the rapidly retreating eastern shoreline, near Ghor Al-Haditha in Jordan. Remote-sensing data highlight links between the evolution of surface stream channels fed by groundwater springs and the development of surface subsidence patterns over a 25-year period. ERT and SP data from the head of one groundwater-fed channel adjacent to the former lakeshore show anomalies that point to concentrated, multidirectional water flow in conduits located in the shallow subsurface (< 25 m depth). ERT surveys further inland show anomalies that are coincident with the axis of a major depression and that we interpret as representing subsurface water flow. Low-frequency GPR surveys reveal the limit between unsaturated and saturated zones (< 30 m depth) surrounding the main depression area. Shear wave seismic reflection data nearly 1 km further inland reveal buried paleochannels within alluvial fan deposits, which we interpret as pathways for groundwater flow from the main wadi in the area towards the springs feeding the surface streams. Finally, simulations of density-driven flow of hypersaline and undersaturated groundwaters in response to base-level fall perform realistically if they include the generation of karst conduits near the shoreline. The combined approaches lead to a refined conceptual model of the hydrological and geomorphological processes developed at this part of the Dead Sea, whereby matrix flow through the superficial aquifer inland transitions to conduit flow nearer the shore where evaporite deposits are encountered. These conduits play a key role in the development of springs, stream channels and subsidence across the study area.

- Article

(52929 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(31366 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Karst landscapes result from the dissolution by water of rocks or semi-consolidated sediments on and below the Earth's surface (Ford and Williams, 2007). Typically, weakly acidic meteoric water percolates into the subsurface, where it dissolves soluble material and enhances its porosity beyond initial matrix porosity and/or fracture porosity (Price, 2013; Hartmann et al., 2014; Goldscheider, 2015). Consequently, a characteristically well-evolved network of subsurface voids and conduits in karst groundwater systems enhances the hydraulic conductivity of the host materials to extremes rarely seen in non-karstified aquifers (Kaufmann and Braun, 2000; Hartmann et al., 2014).

The scale and geometry of karst conduit networks are variable, and they depend upon factors including the lithological characteristics of the host rock, the regional geological and climatic setting and the nature of hydrological recharge (Ford and Williams, 2007; Gutiérrez et al., 2014; Parise et al., 2018). In limestone areas of high annual precipitation, for example, surface dissolution leads to the formation of enclosed depressions (“solution dolines”), which channel surface water into the underground (Waltham et al., 2005; Sauro, 2012). Fractures formed along faults, joints and bedding planes within the host rock can be enlarged by dissolution to create branching networks of caves which are large enough to be entered by speleologists (Palmer, 1991, 2007, 2012; Ford and Williams, 2007). As a result of their global prevalence and ready access, karst systems formed in fractured limestone constitute the bulk of our present understanding of karst drainage systems.

In contrast, karst systems formed by dissolution of evaporites are less common and less studied. Evaporite deposits are commonly poorly bedded and may form constituent parts of marine or lacustrine sedimentary deposits that are semi-consolidated to fully consolidated (Warren, 2006). Due to the extreme solubility of evaporite minerals such as halite, they are only able to form in arid environments (Frumkin, 2013), such that surface recharge is limited as compared to typical limestone karst. Moreover, karst systems in young evaporites are characterized by a more dynamic, changing flow system due to the instability of the flow tubes (Ford and Williams, 2007). Baseflow in these conduits may be of very low discharge, and surface flow may only occur rarely in ephemeral wadis (dry river valleys), where water often flows beneath the surface (Goode et al., 2013; Price, 2013; Salameh et al., 2018).

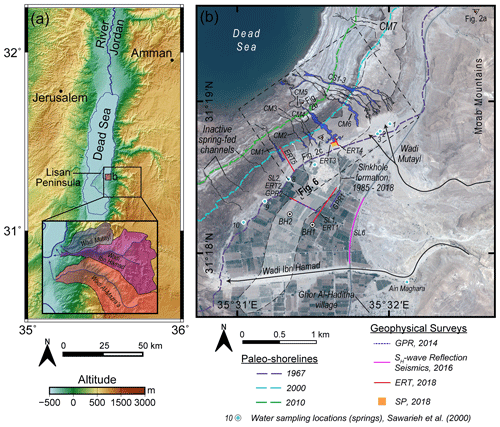

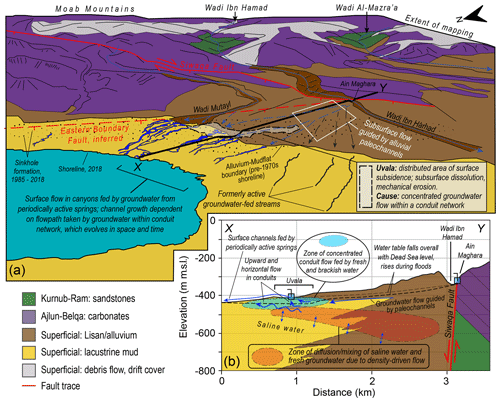

Figure 1Overview of the Ghor Al-Haditha field site. (a) Topographic map showing the location of the study area and field site on the eastern Dead Sea shore, Jordan. Elevation data are derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (Farr et al., 2007). The inset shows the catchments of the three major wadis flowing to the Dead Sea shoreline in the study area: Wadi Mutayl, Wadi Ibn Hamad, and Wadi Al-Mazra'a. (b) Pleiades 2018 satellite image of the study area showing the studied groundwater-fed stream channels (blue) mapped from satellite imagery and close-range photogrammetric surveys. Label CM- refers to meandering-type channels, and CS- refers to straight or braided channels. Geophysical survey lines or areas, as analysed in this work, are marked. Seismic lines SL1 and SL2 refer to S-wave reflection profiles 1 and 2 acquired in 2014 (Polom et al., 2018). The two boreholes of El-Isa et al. (1995) are labelled “BH1” and “BH2”. The area affected by sinkhole formation from 1985 to present is represented by the dashed outline with shaded infill. The numbered blue and white dots represent the approximate locations of groundwater springs sampled during a previous field campaign in the study area in 1999, from Sawarieh et al. (2000), and discussed further in Sect. 2.

One of the most rapidly developing evaporite karst systems on the globe is found on the shores of the Dead Sea (Fig. 1a). This hypersaline terminal lake, fed primarily by the Jordan River, lies within the ∼ 150 km long and ∼ 8–15 km wide Dead Sea basin (Garfunkel and Ben-Avraham, 1996). This basin has subsided rapidly from the late Pliocene to present (Ten Brink and Flores, 2012) due to motion along the left-lateral Dead Sea Transform fault (DSTF) system. During this time, several paleolakes of varying size and duration (Bartov, 2002; Torfstein et al., 2009) have existed within the basin. Since the 1960s, the modern Dead Sea level has declined from −395 to −434 (1967–2020; ISRAMAR, 2020), i.e. by 40 m as of 2020. The lake level fell by 0.5 m yr−1 in the 1970s and by 1.1 m yr−1 in the last decade. This has led to a dynamic reaction of the hydrogeological system and landscape around the lake shore (Kiro et al., 2008). New springs, stream channels, depressions, landslides and sinkholes have formed since the 1980s. These have developed both within alluvial fan sediments deposited by flash floods in wadis terminating at the lake and within mud and evaporite deposits of the former lake bed that have been revealed by the retreat of the shoreline (see e.g. Abelson et al., 2006, 2017; Closson et al., 2007; Parise et al., 2015; Yechieli et al., 2016; Al-Halbouni et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2019, and references therein). The hazards posed by erosion and subsidence result in severe consequences for tourism, agriculture and infrastructure at the Dead Sea (Arkin and Gilat, 2000; Closson and Abou Karaki, 2009; Fiaschi et al., 2018; Abou Karaki et al., 2019).

There are several hypotheses regarding the nature of the subsurface hydrogeology at the Dead Sea and how this relates to the development of rapid erosion and subsidence around the shoreline. There is a consensus that the falling Dead Sea level increases the hydrological gradient adjacent to the lake. This promotes deeper incision of existing stream channels around the lake shore, adjustments in the planform morphology of existing channels (e.g. increased sinuosity), and incision of new channels on the exposed lake bed (Ben Moshe et al., 2008; Bowman et al., 2007, 2010; Dente et al., 2017, 2019; Vachtman and Laronne, 2013). Several studies contend also that the base-level fall results in lateral migration of the freshwater–saltwater interfaces in the subsurface, which enables relatively undersaturated groundwater to invade evaporite deposits previously in equilibrium with Dead Sea brine, thus driving karstification of those deposits and subsidence of the ground surface (Salameh and El-Naser, 2000; Yechieli, 2000; Yechieli et al., 2006). Other studies have argued that karstification is driven primarily (or additionally) by preferential upward flow of fresher groundwater into the evaporite-rich deposits via hydraulically conductive regional tectonic faults (Abelson et al., 2003; Closson et al., 2005; Shalev et al., 2006; Closson and Abou Karaki, 2009; Charrach, 2018). Two main approaches have been used to simulate mathematically such hydrogeological scenarios in or near the DS rift valley: (1) a “sharp-interface approximation” to the transition between hypersaline and fresh groundwaters (Salameh and El-Naser, 2000; Yechieli, 2000; Kafri et al., 2007) and (2) density-driven flow simulations that account for mixing of waters of contrasting salinities and densities (e.g. Shalev et al., 2006; Strey, 2014). Both approaches yield some success within the existing hydrogeological constraints.

There are also varying views of the form and make-up of the subsurface evaporite deposits and varying emphasis on the mechanisms of subsurface erosion that lead to surface subsidence. Many studies invoke chemical erosion (dissolution) of a massive salt layer of up to 15 m thickness and lying at depths of 20–50 m. This layer is proposed to be dissolved by diffuse or fracture-controlled groundwater flow, which results in large intra-salt cavities that then collapse to produce sinkholes (Shalev et al., 2006; Ezersky and Frumkin, 2013; Yechieli et al., 2016; Abelson et al., 2017). Other studies emphasize physical erosion (“piping” or “subrosion”) of weakly consolidated alluvial sand and gravel deposits due to focussed, turbulent groundwater flow in such materials at depths of 5–20 m (Taqieddin et al., 2000; Sawarieh et al., 2000; Arkin and Gilat, 2000). Such studies further propose a combined physical and chemical erosion of thinly interbedded lacustrine salt, marl and clay deposits at the depths of 1–40 m, whereby salt dissolution and clay weakening by relatively fresh groundwater flow generate subsurface cavities and conduits (Arkin and Gilat, 2000; Al-Halbouni et al., 2017; Polom et al., 2018). It is emphasized here that such varying views are not mutually exclusive (cf. Watson et al., 2019). Indeed, some recent studies have emphasized linkages between the surface water flow, groundwater flow in a shallow conduit system and dissolution of deeper-seated salt – particularly during flash-flood events – as an important factor in sinkhole formation (Avni et al., 2016; Arav et al., 2020).

In consensus, however, all mentioned processes lead to mechanical weakening of the underground materials and to subsidence, which is expressed as sinkholes of 1–70 m width and up to 15 m depth and as uvala-like depressions of several hundred metres in width and up to 12 m in depth (Watson et al. 2019). The style of subsidence depends strongly on the mechanical properties of the materials involved (Al-Halbouni et al., 2018, 2019). Both cover-collapse and cover-sag sinkholes occur, according to the classification of Gutiérrez et al. (2014) and Parise (2019).

The use of indirect (non-invasive) methods to investigate subsurface hydrogeology in karst environments presents unique methodological challenges due to the high degree of heterogeneity and discontinuity in the subsurface (Palmer, 2007; Goldscheider and Drew, 2007; Goldscheider, 2015). An overview of indirect methods applied to the Dead Sea sinkhole phenomenon is given by Ezersky et al. (2017). Despite these challenges, near-surface geophysical methods have shown potential for cost-effective investigation of subsurface erosion in evaporite karst environments (see e.g. Wust-Bloch and Joswig, 2006; Jardani et al., 2007; Gutiérrez et al., 2011; Krawczyk et al., 2012; Malehmir et al., 2016; Giampaolo et al., 2016; Fabregat et al., 2017; Abelson et al., 2018; Muzirafuti et al., 2020) and determination of the actual configuration of the fresh–saline water interface (e.g. Kruse et al., 2000; Kafri and Goldman, 2005; Kafri et al., 2008; Meqbel et al., 2013). This is especially the case when geophysical surveys are supported by borehole investigations and other lines of evidence to aid interpretations. Geophysical investigations combined with borehole and hydrogeochemical data on the western shore of the Dead Sea, for instance, provide strong evidence of dissolution of a massive salt layer in the shallow subsurface (as described above) with cavity formation as imaged by high geoelectric resistivities and for linkage of these processes to sinkhole development in many areas there (e.g. Yechieli et al., 2006; Ezersky, 2008; Ezersky et al., 2011). Such evidence is weaker or more ambivalent on the eastern shore, however (Al-Zoubi et al., 2007; Frumkin et al., 2011; Polom et al., 2018).

In this paper, we investigate the relationship between geomorphological change and subsurface groundwater flow on the Dead Sea's eastern shoreline, at a key part of the Ghor Al-Haditha sinkhole site in Jordan. We combine surface manifestations, remote-sensing analysis, and multiple geophysical surveying methods of horizontally polarized shear wave (SH) reflection seismics, electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), self-potential (SP) and ground-penetrating radar (GPR). These are complemented by numerical simulations of the density-driven groundwater flow.

First, we summarize the regional and local geology to aid interpretation of geophysical data and to assign realistic modelling conditions. We then use remote-sensing and surface manifestations to describe the spatio-temporal evolution of a set of stream channels fed by groundwater to show a major shift in the local hydrology associated with numerous sinkhole collapses, particularly at the head of a late-developed major channel formed in the exposed lacustrine deposits at the Dead Sea's eastern shoreline. We then present new ERT and SP datasets gathered at the head of this major channel to image the subsurface flow paths, as well as new ERT data that complement previous shear wave seismic survey data (Polom et al., 2018). We also present new shear wave seismic data further inland, near to the outlet of the main wadi terminating in the area. We provide constraint on the groundwater table by GPR surveys. On the basis of all the above, we hypothesize that flow of subsurface groundwater undergoes a transition from a weakly focused matrix flow near the main wadis to strongly focussed conduit flow near to the shore before feeding the major channel. To test this, we present 2D density-driven groundwater flow modelling that suggests that such conduits are a necessary component of the groundwater system to generate realistic groundwater head and electrical conductivity (EC) conditions in the case of a regressing Dead Sea level. This multidisciplinary analysis leads us to present a refined picture of the groundwater system at Ghor Al-Haditha with improved insight into the links between surface subsidence and erosion and groundwater flow in the case of the regressing Dead Sea.

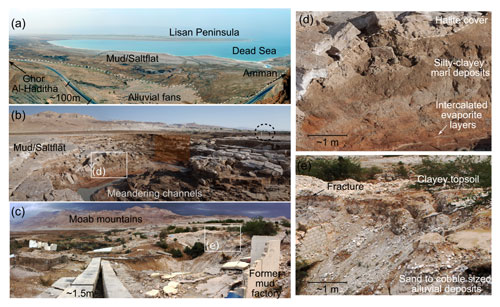

Figure 2Field photos of the Ghor Al-Haditha study area. (a) View from the Moab mountains near Wadi Abu-Darat onto the former Dead Sea lake bed. The dashed white line marks the boundary between alluvium and lacustrine deposits, and it is approximately equivalent to the shoreline position in 1960. (b) Vice versa view from the DS lake bed towards the Moab mountains, with a section of a meandering stream channel and associated deformed ground. (c) Area around canyon CM5 with the destroyed Numeira mud factory. (d) Zoom-in of lacustrine deposits. (e) Zoom-in of alluvial fan deposits.

The Ghor Al-Haditha study area is situated on the eastern shore of the Dead Sea (Fig. 1). The climate is semi-arid to arid, with average annual precipitation of 70–100 mm (El-Isa et al., 1995; Salameh et al., 2018). Three major wadi systems, Wadi Ibn Hamad, Wadi Mutayl and Wadi Al-Mazra'a (or Wadi Al-Karak) terminating in the area, have deposited sequences of semi-consolidated to unconsolidated alluvial fan deposits at the coastline (Figs. 1b and 2a). The drainage basins of the wadis are delineated in the inset of Fig. 1. The catchment areas of the wadis are 30 km2 for Wadi Mutayl, 124 km2 for Wadi Ibn Hamad, and 188 km2 for Wadi Al-Mazra'a. West and north of the alluvial plain, exposure of the former lake bed by the Dead Sea's recession has formed a “mudflat” or “salt flat”.

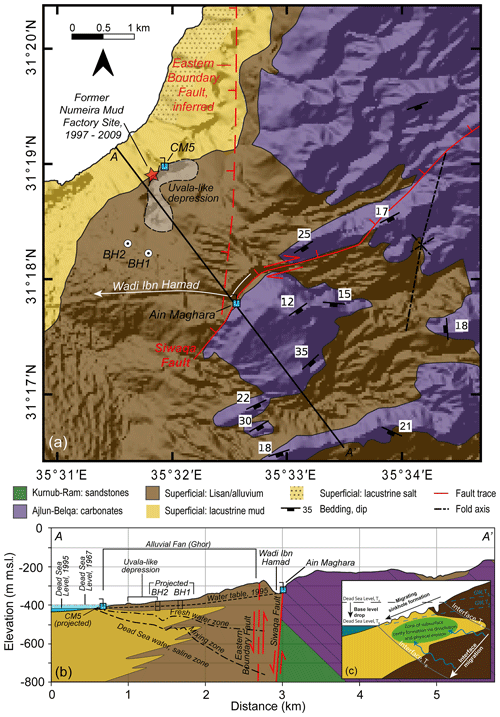

Figure 3Overview of the hydrogeology of the Ghor Al-Haditha study area. (a) Simplified geological map of the study area, partly based on 1:50 000 scale mapping of the Jordanian Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (Khalil, 1992), mapping and reports (IOH and APC, 1995) and partly our own work. The stratigraphy generally dips acutely to the south-east while striking to the north-east. Also shown is the right-lateral oblique Siwaqa fault, the inferred position of the Eastern Boundary Fault (downthrowing to the west), and the axis of the Haditha syncline. The present locations of the groundwater spring rising in the Wadi Sir limestones of the Ajlun group, “Ain Maghara” and the spring rising at the contact between alluvium and mudflat deposits at the head of channel CM5 are also shown along with the location of the large uvala-like depression described in Al-Halbouni et al. (2017) and Watson et al. (2019). A 2D cross section of geology along the line A–A` is shown in (b). The red and black star indicates the position of the Numeira mud factory, which has been defunct since 2009 after being destroyed by sinkhole formation at the site. (b) Cross section of vertical exaggeration x5 depicting the subsurface hydrogeology as reported for the early months of 1995 (El-Isa et al., 1995) based on borehole information, refraction seismic surveys and VES surveys. The projected depth to the Ram-Kurnub sandstones is based on borehole data (IOH and APC, 1995). (c) Inset depicting the hypothesized conceptual model of seaward migration of sinkhole populations at the Dead Sea as the fresh–saline interface migrates with the base-level drop (Salameh and El-Naser, 2000; Yechieli, 2000; Abelson et al., 2003, 2017; Watson et al., 2019). “GW” here refers to the inferred level of the groundwater in the subsurface; squiggly arrows show the movement of water in the subsurface.

The lacustrine deposits comprise alternating, light–dark, laminated to thin layers of carbonates (aragonite, calcite), quartz and clay minerals (kaolinite), with centimetre-scale, idiomorphic halite crystals. These are interbedded with localized thin to thick beds of halite and/or gypsum (Fig. 2b and d), the proportion and thicknesses of which near or at the surface increase lakeward and northward (Al-Halbouni et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2019). The alluvium consists generally of poorly sorted, semi-consolidated to unconsolidated sands and gravels (Fig. 2c and e), which are interbedded with minor silts and clays (El-Isa et al., 1995; Taqieddin et al., 2000; Sawarieh et al., 2000; Polom et al., 2018). At the former stable shoreline, alluvium and lacustrine deposits are in direct lateral contact. Comparable deposits have been widely found along the western shore of the Dead Sea and in numerous boreholes (Yechieli et al., 1993, 2002). Data for the Ghor Al-Haditha study area are considerably less comprehensive, consisting of two boreholes, 45 and 51 m deep, drilled on the alluvial plain in January–February of 1995 (El-Isa et al., 1995; BH1 and BH2, Figs. 1b and 3). Borehole logs show alluvium down to the bottom metre, where a layer of silt and greenish clay was detected. The exact ages of the alluvium and lacustrine deposits are unclear; the exposed lacustrine deposits likely correspond to the regional Ze'elim formation of Holocene age (Yechieli et al., 1993), while much of the alluvium may belong to the Lisan formation of Pliocene–Pleistocene age (Khalil, 1992).

There are three principal aquifer units in the area (Fig. 3) whose characteristics are summed up in the following based on works of Akawwi et al. (2009), Goode et al. (2013), IOH and APC (1995), and Khalil (1992). The first is a lower sandstone aquifer comprising the Ram group and Kurnub formation of Cambrian to early Cretaceous ages, respectively, which is not present at the surface in the study area but outcrops along the escarpment of the DSTF just to the north (cf. Fig. 1c, Watson et al., 2019). The second is an upper carbonate aquifer spanning the Ajlun and Belqa groups of late Cretaceous to early Tertiary age. The third is a superficial aquifer in the Lisan and/or Ze'elim formations. Recharge to the Ajlun-Belqa and superficial aquifers is primarily derived from precipitation in the highlands to the east, where the average annual precipitation is ∼ 350 mm. As on the western side of the Dead Sea (Yechieli et al., 2006), it is estimated that some recharge occurs also via leakage from the lower Ram-Kurnub aquifer (cf. p. 5, Sect. 2.3, IOH and APC, 1995). From these regional aquifers, groundwater flows toward the Dead Sea. A significant spring within the Ajlun group limestones, “Ain Maghara”, can be found just to the east of the study area (Fig. 3). The discharge of this spring is around 0.28 m3 s−1 and is thought to be principally derived (∼ 80 %) from baseflow within the Wadi Ibn Hamad (cf. p. 18, Sect. 5, IOH and APC, 1995), which in turn originates from outcrops of the Ram-Kurnub aquifer unit along the wadi bed upstream of Ain Maghara. The remaining (∼ 20 %) flow is thought to derive from upward leakage from the Ram-Kurnub aquifer. Several springs are found in the transition between the alluvium and lacustrine deposits; these feed surface streams that drain into the Dead Sea via numerous channels (Fig. 1b and 2b). Other surface stream channels in the lacustrine deposits lack these groundwater-fed springs and are instead fed by surface water from wadis during flash-flood events. A borehole drilled in the wadi bed just upstream of Ain Maghara confirms subsurface water flow within the wadi bed with a similar chemistry to that of the spring, though the depth and nature of this flow are not recorded. Head elevations in the vicinity of Ain Maghara were reported to be −300 to −350 in 1994 (cf. p. 5, Sect. 2.2, IOH and APC, 1995). The depth to the water table in the superficial aquifer at the time of drilling in 1994 was 20.5 m in BH1; no depth was apparently recorded for BH2 (El-Isa et al., 1995). A groundwater well just over 5 km south of the study area, at the Al-Mazra'a pumping centre, indicates that the groundwater head level in the superficial aquifer declined at an average rate of 0.75 m yr−1 from 1960 to 2010, whilst over the same time period the measured electrical conductivity had increased by 59 µS yr−1 (Goode et al., 2013).

The first published report of geophysical investigations in the study area is El-Isa et al. (1995), which includes results of classic refraction seismic and vertical electrical sounding (VES) surveys conducted in 1994. Several anomalies present in the refraction seismic data were inferred to represent buried alluvial channel deposits at 5–10 m depth, just south-west of BH2 (in the centre of their profile 4 and at the southern end of their profile 5; cf. Figs. 4.9 and 4.11 in El-Isa et al., 1995). Ten VES traverses were performed in the study area using an Atlas-Copco SAS-300 system. The combined inversion of survey data across all traverses, calibrated with respect to the hydraulic head measured in the boreholes, enabled El-Isa et al. (1995) to create a layered 2D interpretation of groundwater conditions, consisting of an uppermost “dry” area (resistivities of 120–660 Ωm), a fresh groundwater layer (resistivities of 10–80 Ωm), a brackish zone where groundwater and Dead Sea water mixing occurs (resistivities of 2–8 Ωm) and then saline Dead Sea water (resistivities of < 1 Ωm) and is sketched in Fig. 3b. The water levels in the boreholes were combined with spring elevation data to determine a hydraulic gradient of roughly 30 m km−1 from east to west, following the surface topography.

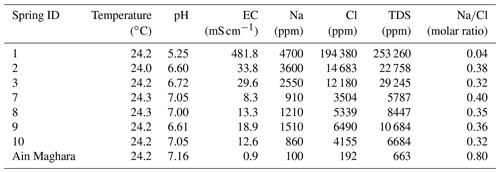

Table 1Water geochemistry of samples taken from groundwater springs during the 1999 field campaign of Sawarieh et al. (2000). Spring ID numbering is that used in the 1999 field campaign report; spring locations are shown approximately in Fig. 1b.

A second report, by Sawarieh et al. (2000), includes additional refraction seismic surveys, as well as water chemistry, temperature, pH and EC of springs, wells and sinkholes undertaken in February 1999 (see Fig. 1b for the locations of the springs sampled). The seismic results generally resolved an up to three-layer velocity model, thought to represent differing levels of compaction of alluvium. The hydrology of the study area has changed since the survey: several springs which they sampled in the area of Wadi Mutayl have now dried up, and the sampled locations do not match those of the groundwater springs feeding channels CM1–3 and CM6 (Fig. 1b). Groundwater samples were analysed for anion and cation concentrations and total dissolved solids (TDS) in the laboratory at the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of Jordan (MEMR). The results are summarized in Table 1. In general, the measured TDS increased from east to west: groundwater sampled at Ain Maghara could be defined as between fresh and brackish (EC: ∼ 0.7–0.9 mS cm−1; TDS: ∼ 500–700 ppm), whereas water rising from the springs closer to the shore would be categorized as brackish (EC: 1.5–50 mS cm−1; TDS: 500–35 000 ppm), aside from their sample 1, which had abnormally high EC and TDS, being more of a brine. The molar ratios of water samples from these springs were relatively low. The EC readings from the field broadly correlate with the proportions of TDS and Na+ and Cl− ions measured in the water samples.

From 2009 to 2010, scientists of MEMR performed geophysical surveys using ERT, GPR, and transient electromagnetic techniques (TEM, Alrshdan, 2012). GPR data acquired with a SIR-10B system near the mud factory were interpreted as very shallow (< 7 m) sinkhole and subsurface water conduits; the same relates to surveys further inland. The used 100 MHz antenna and wet and saline ground conditions strongly restricted the penetration depth of the GPR signal (Alrshdan, 2012). Similar GPR investigation of the shallow subsurface and sinkhole formation was reported by Batayneh et al. (2002). ERT surveys were performed traversing the alluvium–mudflat boundary close to CM1 and the former mud factory site and further inland in farmers' fields parallel to the road along which ERT1 was performed in this study. The survey lines near the mud factory imaged some extremely high-resistivity anomalies (> 10 000 Ωm) thought to represent subsurface cavities. Three ERT profiles were acquired with the IRIS Syscal system by Al-Zoubi et al. (2007), in the sinkhole area NE of Wadi Ibn Hamad. The higher resistivities up to 600 Ωm were interpreted as fractured alluvial material, while low resistivities of less than 20 Ωm were recorded at the bottom of all the profiles. Further ERT, GPR, TEM, magnetic and seismic measurements including multichannel surface wave analysis were performed on the agricultural fields (Camerlynck et al., 2012; Bodet et al., 2010), the seismics part of which has been reported by Ezersky et al. (2013a, b). The two ERT profiles acquired further north in the study area also imaged high-resistivity anomalies (Frumkin et al., 2011), which they interpreted as representing subsurface cavities. All ERT and GPR surveys on the alluvial fan deposits only penetrated to a maximum depth of 25 m, which was insufficient to image the water table in this area.

The most recent geophysical survey of Polom et al. (2018) comprises a summary of shear wave reflection seismic data collected in 2013/14. These data were interpreted as incompatible with a proposed 2–10 m massive salt layer at around 35–40 m depth (Ezersky et al., 2013a) but did reveal zones of high S-wave scattering in the subsurface near the main depression as well as potential buried and refilled channel systems within the alluvial fan architecture and a deeper-lying silt and clay layer at around 60–80 m depth.

Our multidisciplinary investigation of surface and subsurface hydrology at Ghor Al-Haditha in Jordan consists of (1) remote sensing based on satellite imagery and aerial photogrammetric image analysis, (2) geophysical methods such as ERT, SP, GPR and SH-wave reflection seismic surveys, and (3) 2D hydrogeological modelling of density-driven groundwater flow. Detailed theoretical concepts and additional results of the methods are illustrated in Appendix A.

3.1 Remote-sensing and field surveys

The remote-sensing dataset comprises high-resolution optical satellite imagery and aerial photographs that span the years 1967 to 2018. The dataset is identical to that presented in Table 1 of Watson et al. (2019), save for an additional Pleiades optical satellite image acquired on 23 April 2018. Temporally, the satellite and aerial imagery dataset is decadal in resolution from 1967 and annual in resolution from 2004, with spatial resolutions from 2 to 0.3 m pixel−1. The remote-sensing data are complemented by very high-resolution (0.1 m pixel−1) orthophotos and digital surface models derived by photogrammetric processing of optical images obtained through balloon- and drone-based close-range aerial surveys of the study area in 2014, 2015 and 2016 (cf. Table 1, Watson et al., 2019).

The satellite images were pre-processed (orthorectification, pansharpening and georeferencing and co-registration) by using the PCI Geomatica Orthoengine software package, as described in Watson et al. (2019), except for the 2016, 2017 and 2018 Pleiades images which were orthorectified and georeferenced by Airbus. For details of the method for generation of the orthophotos and DSMs from photogrammetric survey data, see Al-Halbouni et al. (2017). After pre-processing, all remote-sensing and photogrammetric datasets were integrated within the Q-GIS Geographical Information Systems (GIS) software package for geographical analysis, which included the manual digitization of fluvial and karst features in order to reconstruct their development through both space and time.

Maps derived from remote-sensing and photogrammetric data were extensively ground-truthed over the course of four field campaigns in October 2014, October 2015, December 2016 and October 2018. The drone and balloon surveys were performed in conjunction with the first three field campaigns. In 2015, we also made a preliminary survey of water bodies in the study area. Temperature and electric conductivity were measured in situ at numerous springs and ponds (within sinkholes) with a Hach HQ40D Portable Multi-meter. These measurements were repeated for selected springs and ponds during the 2018 field campaign.

3.2 Geophysical surveys

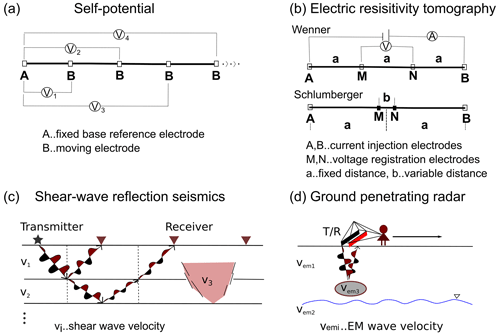

3.2.1 Self-potential

The self-potential (SP) method is a passive geophysical method that measures the electric potential between two non-polarizing electrodes connected on the ground surface of the Earth. More information on the physical background of the SP method is given in Appendix A.

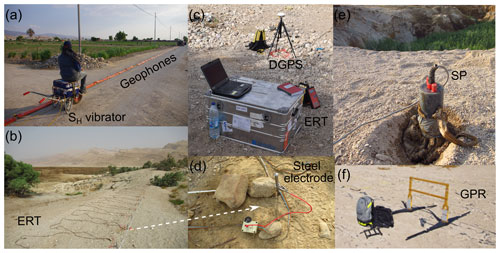

Figure 4Ground-based images of the ERT, SP and seismics equipment. (a) Seismics line 1 with landstreamer geophone system and ELVIS SH shear wave generator system. (b) ERT line 3 at the head of canyon CM5 with electrode chain ActEle spread. (c) ERT Lippmann 4point light and DGPS Trimble ProXRT-2 equipment. (d) Close-up of stainless-steel electrode, connecting cable and switch box of the multi-electrode ERT system. (e) SP Ag–AgCl electrode in a cotton bag filled with bentonite and watered to improve electric ground coupling. (f) GPR Malå Ramac device with a 50 MHz transmitter and receiver antennas.

Our SP survey was conducted in 2018 (for the location, see Fig. 1b). We used the fixed base configuration (Fig. A1a), with a high impedance (> 50 MΩ) Voltcraft voltmeter and several non-polarizable Ag/AgCl electrodes for the survey (Fig. 4e). The semi-permeable bottom filters of the electrodes are covered by a thick, wet bentonite mass inserted into a closed cotton bag. In this configuration, the electric potential is measured between a fixed base reference electrode and a moving electrode. Adapted to our survey area, we measured parallel profiles to form an array configuration with an inter-electrode spacing of 10 m. The reference electrode, with the convention that the negative pole should be N or E of the positive pole, is buried and watered by using freshwater to improve electrical ground coupling. The moving electrodes are also watered, and after the signal stabilized, we took at least three measurements for each point. More details on the SP array can be found in the results (Sect. 4.2.1).

3.2.2 Electric resistivity tomography

Electric resistivity tomography (ERT) is an active geophysical method within the family of geoelectric methods. Geoelectrics were developed initially as vertical electric sounding (1D) to determine groundwater in the subsurface (Schlumberger, 1920) by injection and recording of an electric field using two pairs of electrodes. More details on the physical background of ERT are given in Appendix A.

Our ERT survey was performed in October 2018 by using a Lippmann 4point light 10 W direct current instrument (Grinat et al., 2010) and stainless-steel electrodes connected to the Lippmann multichannel cable system (Fig. 4b–d). Data were collected by using a multichannel control system implemented in the Geotest v. 2.46 software (Rauen, 2016) with automatic combination of all possible injection (AB) and measuring (MN) pairs of electrodes using a measurement interval frequency of 8 Hz. Different survey configurations for certain field conditions and penetration depths were tested on site prior to the survey. Multichannel geoelectric control systems commonly enable a combination of different general electrode configurations, i.e. Wenner, Schlumberger and several dipole–dipole configurations. The multichannel control system used here was a combination of Wenner and Schlumberger configurations (Fig. A1b) which incorporates the advantages of both general configurations regarding advantages of lateral mapping and deep sounding. In profiles along the roads (ERT1 and ERT2) we used the so-called roll-along technique to provide a combination of long profile distances (0–600 m) with short inter-electrode distances (1–5 m). Repeated measurements have been performed at certain electrode positions in case of non-reliable high-resistance (> 1 KΩ) results and with the support of freshwater to improve electrical ground coupling. Remaining anomalous data points (showing e.g. physically implausible negative resistivities or non-reliable local high resistivities) have been carefully removed from further analysis.

3.2.3 Shear wave reflection seismics

The shear wave reflection seismics method uses the principles of reflection seismology (Sheriff and Geldart, 1995), which is widely applied in hydrocarbon exploration and explained more in Appendix A.

The shear wave seismic surveys reported on here used horizontally polarized S waves (SH waves) and were undertaken in October 2014 and December 2016. Details of the data acquisition and processing applied regarding profiles SL1 and SL2, which were acquired in 2014, are reported in Polom et al. (2018). Profile SL6 was acquired in 2016 using the same acquisition method and parameters. The profile was positioned perpendicularly to the main structure dip of the Wadi Ibn Hamad alluvial fan with the intention of imaging a cross section of probable fluviatile subsurface channel structures at the eastern boundary of the alluvial fan.

3.2.4 Ground-penetrating radar

Ground-penetrating radar uses the active emission of electromagnetic waves in the microwave band from a transmitter to a receiver antenna to investigate the relative dielectric permittivity of the shallow subsurface (Fig. A1d). The physical background of GPR is explained in Appendix A.

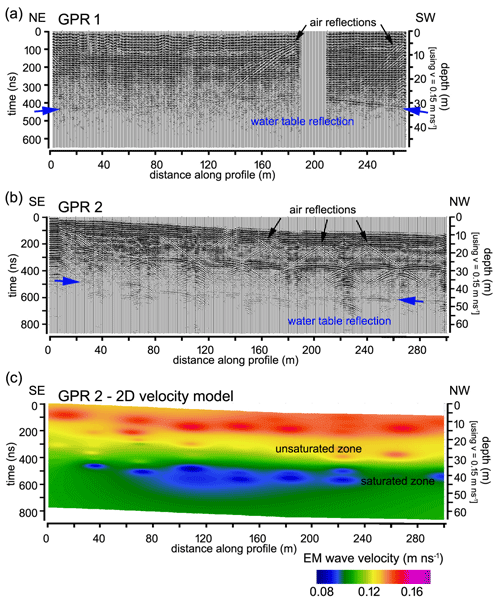

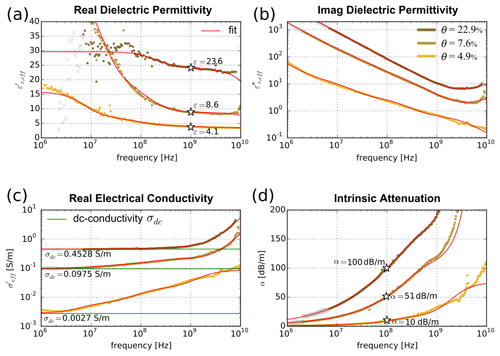

All GPR surveys were conducted in October 2014 in common offset mode (transmitter and receiver antennas move simultaneously across a linear transect at a fixed distance) using a RAMAC GPR CU II system from Malå Geosciences (Fig. 4f). Several transects were collected using both 100 MHz and 50 MHz unshielded antennas, although only results from the latter are reported here for a total of two transects (GPR 1 and GPR 2 in Fig. 1b) that followed ERT surveys. Time-to-depth conversion for radargrams was based on estimates of electromagnetic wave velocities from three different approaches: (1) from diffractions in common offsets, yielding velocities ranging between 0.09 m ns−1 for deeper materials and 0.15 m ns−1 for surficial sediments, (2) from field calibrations using a metal rod at a depth of 1.2 m buried on the wall of a collapsed sinkhole, with values ranging between 0.15 and 0.2 m ns−1, and (3) from samples collected in the field at approximately 2 m deep in a sinkhole wall and measured in the lab under different moisture contents, reaching average values of 0.15 m ns−1 for the driest (5 % moisture content) conditions (Appendix A). The mean dielectric permittivity value hence lies around εr∼ 4, typical for dry sand.

Processing of common offset profiles was conducted with ReflexW v9.0 by Sandmeier Geophysical Research (Sandmeier, 2019). Steps were limited to (1) substract mean (dewow), (2) background removal, (3) manual gain, (4) bandpass frequency, (5) Kirchhof migration (based on an average velocity of 0.15 m ns−1), and (6) topographic correction. In some instances (i.e. GPR2 transect) the presence of isolated point reflectors (Neal, 2004) resulted in the presence of diffraction hyperbolas in common offset profiles, allowing the construction of 2D models of velocity.

3.3 Inversion and numerical modelling techniques

3.3.1 Inversion of SP and ERT data

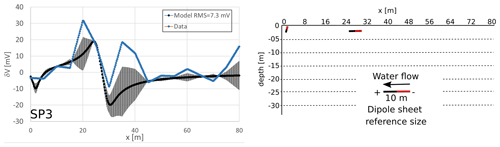

In this study, all SP anomalies were assumed to be generated by a 2D polarized sheet that is inclined and thin and that has an infinite extent perpendicular to the SP profile, in the following called “strips”. Therefore, the model parameters are the position of the centre of the strip along the profile (xo), its depth (h), the inclination angle (αi) and the half-width of the strip (a) and the polarization factor or electric dipole density (k). The particle swarm optimization (PSO) method was applied to determine values of those parameters (Monteiro Dos Santos, 2010). The PSO algorithm was first described by Kennedy and Eberhart (1995): it is a stochastic algorithm that simulates features of the social learning process as sharing information and evaluation of behaviours. The algorithm considers a community of N different models, and each model is updated taking into account its lowest rms achieved so far (called the “pbest model”) until the best model by any model of the community (called the “gbest model”) is obtained. The final solution will then be the gbest model achieved at the end of the iteration process.

The resistivity data were inverted by using the commercial program RES2DINV (GEOTOMO) v. 3.5 (Loke and Dahlin, 2002) that applies the Gauss–Newton inversion scheme. In a 2D model the Earth section below the acquired profile is divided into numerous rectangular cells. The objective of the inversion procedure is to vary the resistivity value of each cell in order to find a collective resistivity response that best matches the apparent resistivity measured. The forward problem of the Jacobian matrix value calculation is hereby addressed by a finite-element simulation, that is, to calculate the apparent resistivity response of a specific resistivity distribution. A non-linear L1 norm optimization method with smooth constraints is used to calculate the change in the resistivity of the model cells to minimize the difference between calculated and measured apparent resistivity (Loke et al., 2018; Sjödahl et al., 2008).

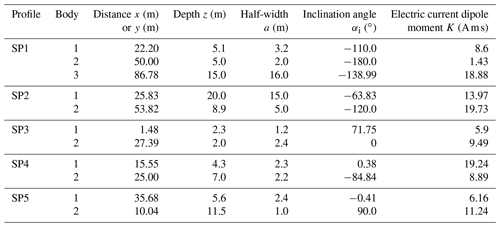

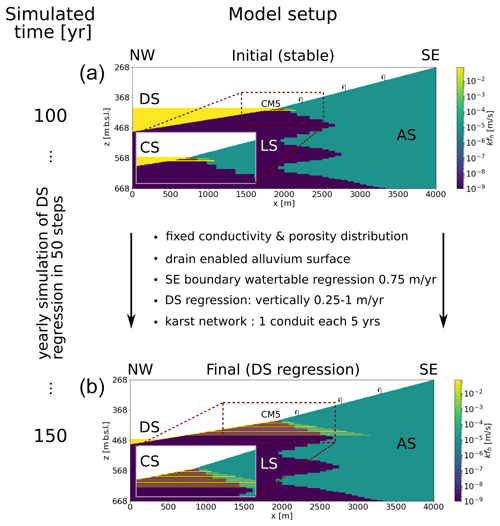

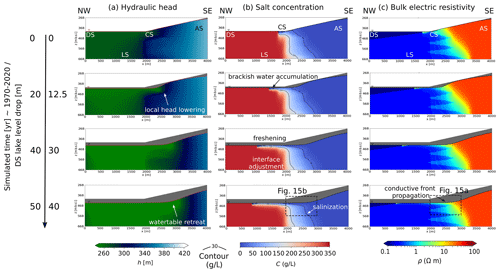

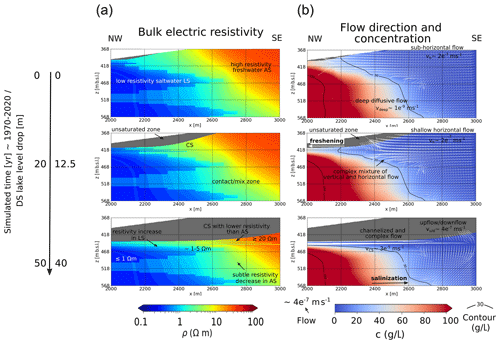

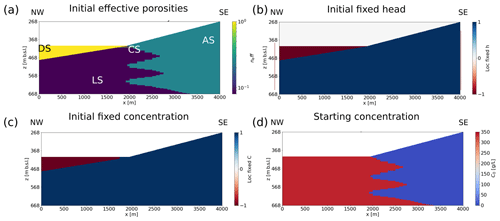

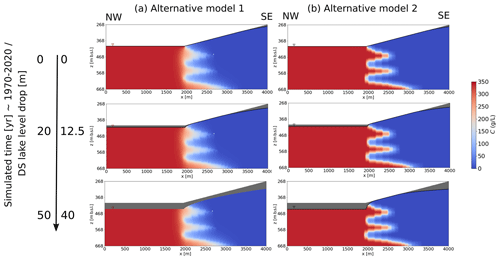

Figure 52D hydrogeological model and simulation time setup. The hydrogeological unit abbreviations are DS – Dead Sea, AS – alluvial sediments, LS – lacustrine sediments and CS – conduit system. Units are coloured by their horizontal hydraulic conductivity (kfh). The text gives a description of the modelling approach between the initial (a) and final (b) states, the latter after 50 years of simulated DS regression. The simulated karst network evolution is presented as a zoomed-in view in the insets within each image. Top of alluvium is considered freely draining. The top centre of the model corresponds roughly to the location of the outflow point of canyon CM5; the profile follows the NW section of the AA′ line of Fig. 3.

3.3.2 Hydrogeological modelling

A 2D hydrogeological forward model was developed by using Modflow v. 2005, Mt3DMS and Seawat v. 4 as integrated in the FloPy environment (Bakker et al., 2016; Lee, 2018) to understand the effects of the falling Dead Sea level and of the hypothesized development of karst-related conduits on the groundwater system. With this model of falling base level, we simulated the evolution of groundwater level and salinity distribution in the superficial aquifer system along a 4 km long transect perpendicular to the shoreline of the Dead Sea (i.e. along a roughly NW–SE-orientated profile following the NW section of profile AA′ in Fig. 3, with the centre approximately at the head of canyon CM5). The model salinity distribution provided electrical resistivity values that were compared to those estimated from the ERT inversions. The 2D hydrogeological model setup and approach are presented in Fig. 5.

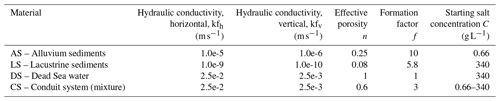

The lithological units simulated in the model are (1) alluvial fan sediments (“alluvium”), which comprise sand and gravels and which form a superficial aquifer, and (2) lacustrine sediments (“mud”), which comprise interbedded evaporites (such as gypsum, aragonite, calcite, and halite) and carbonates in clay to silt size (Khlaifat et al., 2010) and which are considered an aquiclude (Abelson et al., 2006; Siebert et al., 2014; Strey, 2014; Sachse, 2015). Geologically, these lithological units represent, respectively, the terrestrial and lacustrine facies of the Pleistocene Lisan and/or Holocene Ze'elim formations. Alternating layers of alluvium and lacustrine sediments have been simulated to take into account the local geology at Ghor Al-Haditha, where a silty-clay layer lying under the alluvium is reported in boreholes and has been imaged seismically at 40–80 m below the surface at a distance of roughly 1 km from the ∼ 1967 Dead Sea shoreline (El-Isa et al., 1995; Taqieddin et al., 2000; Polom et al., 2018). A similar geometric arrangement of aquifers and aquicludes is shown from boreholes for the western shore of the Dead Sea (cf. Yechieli et al., 2006).

The model dimensions are 4000 m by 400 m (Fig. 5), and the model is discretized into a grid of 1 m wide by 0.5 m high cells. The Dead Sea (with a density of 1240 g L−1, e.g. Siebert et al., 2014) is included towards the west. Hydraulic heads are calculated based on a reference datum defined at 668 m below mean sea level. No flow is assigned to the bottom of the aquifer system. Boundary conditions of constant head are defined at the Dead Sea level in the north-west and a dropping water table by 0.75 m yr−1 in the south-east, according to the nearest available well measurements (cf. Sect. 2). The shrinkage of the Dead Sea is simulated as a yearly fall in the hydrological base level by 0.5 m vertically for 10 years, 0.75 m vertically for 20 years and 1 m vertically for another 20 years according to estimations by Watson et al. (2019).

The hydraulic properties in the model are mostly estimated in the absence of laboratory or in situ data, and they are chosen to represent a simple aquifer–aquiclude system (Table 2). The horizontal hydraulic conductivities of kh = 1 × 10−6 m s−1 for alluvium and kh = 1 × 10−10 m s−1 for lacustrine sediments are taken as mean values from the literature as adapted for the DS in studies from Shalev et al. (2006), Strey (2014), and Sachse (2015). An important assumption adapted to the local geologic findings is that vertical hydraulic conductivities are assumed to be 10 times lower than the horizontal ones. This represents anisotropy imparted from sedimentological layering and assumes the dominant role of bedding over tectonic-related anisotropy (i.e. fault-controlled flow) in this particular area (cf. Sect. 2). Hydraulic conductivities for the Dead Sea and for the hypothesized conduit system have been selected after various parameter tests. We added 1 m deep horizontal conduits of high effective porosity and hydraulic conductivity (Table 2) to the system in each fifth year of simulation. Due to the groundwater-level decline and shoreline recession, the horizontal extent of later-formed and deeper-lying conduits is greater than of earlier-formed and shallower conduits. Furthermore, we added drain cells to the whole surface of the alluvium cover to account for the surface channel systems that existed before regression of the Dead Sea (cf. Sect. 4.2.5). Conduit effective porosity and hydraulic conductivities were first varied in a trial-and-error approach to achieve model convergence and realistic steady-state hydraulic results, as further explained below in Sect. 4.3.

We simulate density-driven groundwater flow based on salt concentration in the porewater. The modelling approach is to first simulate the saline water distribution in an estimated steady state over 100 years before the Dead Sea started retreating and to use this as the initial condition for simulating the yearly lake recession. The starting salt concentration of 340 g L−1 is adopted for the Dead Sea and for the lacustrine sediments, which are assumed to be initially saturated with Dead Sea water. A constant salt concentration is defined for the Dead Sea only. “Salt” hereby stands as a proxy for all types of dissolved evaporite minerals in the numerical modelling, with NaCl as the main component. The lacustrine sediments are assumed to be subject to a continuous fresh or slightly brackish water inflow of initial salt concentration 0.66 g L−1, through the alluvial sediments, which is based on values of the Ain Maghara spring (Table 1). A hydraulic head gradient of ∼ 30 m km−1 (cf. Sect. 2; El-Isa et al., 1995; Sawarieh et al., 2000) is set, which is similar to the topographic gradient in this area (Al-Halbouni et al., 2017). Basic diffusion and advection processes are added by using appropriate parameters for the different aquifer–aquiclude materials (Table 3). Convergence limits of the changes in hydraulic head between two iterations were set to 1e-4; the same holds for changes in the concentration. Formation factors, effective porosities and the salt diffusion coefficient are known for the Dead Sea sediment analysed samples of the western side of the lake (Yechieli and Ronen, 1996; Ezersky and Frumkin, 2017). Transport steps and dispersivities have been derived from different saltwater intrusion studies and the classical Henry problem (Croucher and O'Sullivan, 1995; Geo Slope, 2004; Abarca et al., 2005; Langevin and Guo, 2006; Zidane et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2019). For an overview of the initial spatial distribution of the effective porosity, concentration and head parameters, please refer to Appendix B.

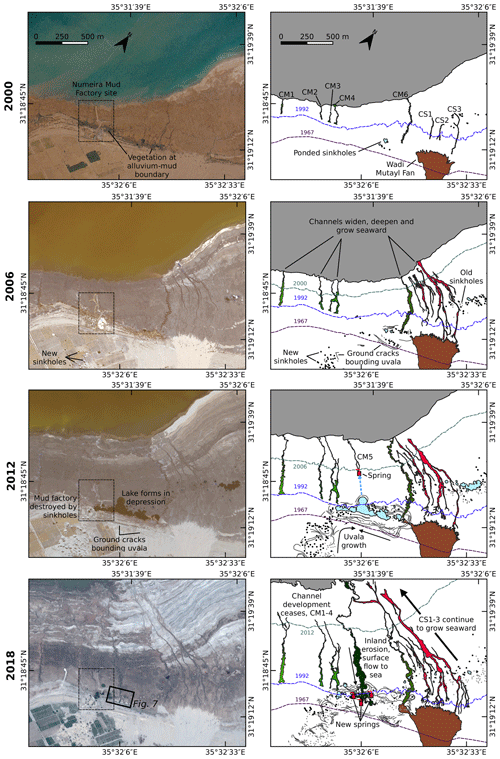

Figure 6Evolution of stream channels and karstic depressions from 2000 to 2017. Left column shows aerial or satellite imagery. The image sources are aerial survey of the RJGC (2000); Quickbird satellite (2006, 2012) and Pleiades satellite (2018). Right column shows maps of channels (red: straight/braided, green: meandering), ground cracks denoting the limits of a large-scale depression, and depression or sinkhole-hosted ponds (blue). Flow has converged upon CM5 in the years following 2012, with the other channels ceasing to prograde shoreward.

We estimate the bulk soil electric resistivities ρ in our models from the salt concentration by using transformation equations between chloride concentration and TEM resistivities (Ezersky and Frumkin, 2017). Hereby we rely on water resistivity vs. salinity relationships developed from borehole studies (Ezersky and Frumkin, 2017; Yechieli et al., 2001) and refer to the TDS content rather than the chloride concentration in our simulations.

We can derive the bulk soil resistivities via by using Archie's law (Archie, 1942) even for the clay-containing DS sediments, as they do not present a cohesion and cation exchange effect according to Ezersky and Frumkin (2017).

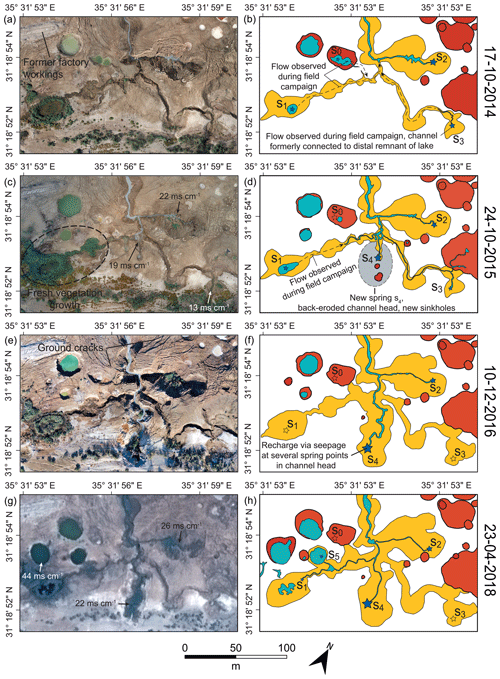

Figure 7Evolution of the canyon–spring–sinkhole system close to the former mud factory at the head of CM5. (a, c, e) show aerial (balloon and drone, 2014–2016) or satellite imagery (2018). (b, d, f) show maps of the channel (yellow), surface water (blue) and sinkholes (dark orange). Filled stars indicate active springs; empty stars indicate previously active springs. The size of the filled stars indicates the approximate relative contribution of that spring to the flow downstream of the T junction between waters of the easterly and westerly springs.

4.1 Remote-sensing and field surveys

The new observations presented here regarding the geomorphological evolution of Ghor Al-Haditha are focussed on the area around the site of the former Numeira mud factory (Fig. 6), which is coincident with the area in which the new geophysical surveys were conducted (see Fig. 1b for an overview). Here, stream channels of two distinct morphologies have been cut into the exposed evaporite-rich mud deposits of the former Dead Sea lake bed: meandering (CM) and straight (CS). The heads of all meandering channels have developed at spring points (in most cases, one per channel). Such springs lie either at the alluvium–mudflat boundary or within the mudflat deposits, and they originated at points lying over 100 m seaward of – and several metres below – the 1967 lake level. The heads of straight channels do not correspond to spring points; they initially developed some distance out on the mudflat, downslope from the termination of the active alluvial fan of the Wadi Mutayl.

As the shoreline has progressively retreated, both channel types have grown seaward, incising new channel segments into the lacustrine deposits of the former lake bed as the shoreline retreats over time. While the straight channels also show upstream growth (e.g. CS1–3 in Fig. 6), most meandering channels show little or no upstream growth (e.g. CM1–4 and CM6 in Fig. 6). Established sections of both channel types also widen progressively with time. From field observations, channel widening is commonly associated with fault-delimited slumping of the channel sides (Al-Halbouni et al., 2017). Both channel types deepen with time in response to the fall in base level; vertical incision is the primary fluvial erosive response to base-level fall. The lower sections of the straight channels are commonly braided and contain deposits ranging in size from sand to cobble. Deposit grain sizes within the meandering channels are mud to silt.

Sinkholes began developing in the area around the Numeira mud factory sometime after 1994, having first developed in the south of the study area in the mid-1980s (Sawarieh et al., 2000; Watson et al., 2019). By 2000, a cluster of water-filled holes lay along the alluvium–lacustrine boundary to the north-east of the factory site, while another cluster had formed on the alluvium about 750 m to the south of the factory (Fig. 6). Between 2008 and 2012, sinkhole development in this part of Ghor Al-Haditha accelerated dramatically and migrated from both the initial clusters toward the factory site. In close spatio-temporal association with sinkhole development was the formation of a gentle uvala-like depression (Fig. 6). This depression formed on a scale much larger than the individual sinkholes, and much of its perimeter is delimited by numerous ground cracks and faults (Watson et al., 2019). By 2012, the section of this uvala along the boundary between alluvium and lacustrine sediments was occupied by a small lake.

A remarkable meandering channel, whose development highlights spatio-temporal links between subsidence and groundwater outflow, is CM5. This formed in the summer of 2012 with its head initially located in the middle of the mudflat, about 750 m from the alluvium–mudflat boundary (Fig. 6). Headward channel incision progressed rapidly upstream over 3 months, in association with the drainage of the lake that had formed within the uvala (see Al-Halbouni et al., 2017, for details). Incision and headward erosion continued at a slower rate up to 2018. The main springs feeding CM5 all lie near the centre of the uvala, at or near its deepest points. Since the establishment of CM5 in 2012, the growth of nearby meandering channels CM1–4 has diminished markedly. Similar spring-fed meandering channels further south-west also seem to have ceased developing shortly before 2012 (Fig. 1b). Also, aside from one locality ∼ 500 m to the south-west, sinkhole development within the uvala since 2012 has been focussed within a 200 m radius of the head of CM5.

Figure 8Field impressions of conduits and karstic groundwater springs at Ghor Al-Haditha. (a) Nested sinkhole in the alluvium (located in the southern part of the uvala) intersecting a further cavity or pipe. Photo: Damien Closson, 2008. (b) Sinkhole in lacustrine mudflats (located just inland of CM7; photo taken 2018) with pipe disappearing toward the top of the picture. (c) Conduit formed in lacustrine mudflat deposits near to the shoreward termination of CM1 (photo taken 2014). The flow has excavated a conduit in the weaker mud deposits below a more competent evaporite lamination. (d) Spring s4 at CM5 at baseflow rate (estimated discharge: 2 × 10−4 m3 s−1). The main stream is fed by several similar seeps within the depression at the channel head. Photo taken: 2018. (e) s4 during high flow 3 d after an intense rainfall event (estimated discharge: 2 × 10−1 m3 s−1). Photo taken: 2015, modified after Al-Halbouni et al. (2017). (f) Close-up of s4 during high flow. The nature of the sediment load varies from fine sediments to pebble-sized clasts (up to 5 cm in diameter). Photo taken: 2015, modified after Al-Halbouni et al. (2017).

More detailed evidence of the dynamic development of erosional and subsidence features around the head of CM5 during the period 2014–2018 is shown in Fig. 7. After its establishment in 2012 (Fig. 6), channel CM5 was fed by a complex suite of springs whose activity varied considerably between field campaigns in 2014–2018. In 2013, three springs, s0, s1, and s2, fed the channel, with flow from s2 rapidly eroding a new path to the main channel between June 2013 and September 2014. By the October 2015 field campaign, most of the flow into CM5 was now provided by a new spring to the south, s4. Active collapses of the s4 stream head were observed over the course of a few days, between 25 and 28 October 2015, when a large rainfall event occurred, associated with flash floods locally elsewhere. These stream head collapses occurred in conjunction with sinkhole openings along a line 20–30 m directly upslope of the stream head (Fig. 7). Flow rates near the channel head were around 2 × 10−1 m3 s−1, and coarse-sand to pebble-sized material was suspended in the flow (Fig. 8e–f; cf. video supplement). The other springs had either dried up or provided much reduced discharge to the channel. By December 2016, these sinkholes had been obliterated, as continued collapse and erosion produced a new section of the channel with concurrent landward migration of spring s4, which continued to be the main source of flow within the channel. The nature of s4 was by now a proliferation of seepage points in the channel head (Fig. 7). Discharge at one of these seeps was measured to be 2 × 10−4 m3 s−1 in 2018, 3 orders of magnitude lower than during the high-flow event of 2015, and only fine sand and silt particles were suspended in the flow (Fig. 8d). This low discharge is also in line with qualitative observations of a low discharge rate at CM5 in 2014 and 2016 (as compared to the 2015 high-flow event). Between December 2016 and October 2018, new water-filled sinkholes of considerable diameter (∼ 30 m) had formed west of CM5. One of these holes was a new source of discharge to the canyon and is labelled s5.

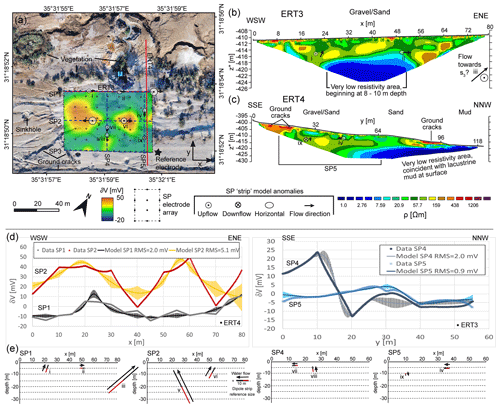

Figure 9Summary of SP and ERT survey results at the head of CM5. (a) Map showing the arrangement of the SP electrodes in an array and the resulting heatmap of potentials (with reference to a fixed electrode at the south-eastern side of the array) overlain on an orthophoto from December 2016. The locations of the inverted profiles SP1–SP5 and their associated strip model anomalies are labelled, along with the modelled flow directions for the anomalies. Also marked are the locations of springs s1, s3, and s4. (b) Electric resistivity distribution along ERT profile 3, which used a Wenner configuration with an electrode spacing of 1 m. Data inversion gave an rms error of 4.4 % after eight iterations. The observed surface material and the locations and flow directions of SP strip anomalies are labelled. (c) ERT profile 4, which used a Wenner configuration with an electrode spacing of 2 m. Data inversion gave an rms of 10 % after five iterations. The observed surface material and the locations and flow directions of SP strip anomalies are labelled. (d) SP lines 1, 2, 4 and 5 data and derived best inversion model results with an indication of rms error. (e) Graphical representation of polarized strip anomalies matching the modelled SP line data. The direction of water flow along a strip to produce the inverted anomalies is generally from minus (red) to plus (black). Due to noise in the data, the exact peaks in the modelled self-potential curves are not always reached. All results from inversion of SP3 have been omitted from all figures for clarity; to see these results, see Fig. A2 in Appendix A.

In situ EC measurements, as well as persistent localized vegetation growth around the ponds and in streams (Fig. 7), indicate the discharge of brackish groundwater from these springs. EC values from October 2015 for each of the springs s1–s4 range from 13 to 22 mS cm−1. Repeated in situ measurements in November 2018 at s2 and s4 were slightly elevated as compared to 2015 but show similar values of 26 and 22 mS cm−1. For context, note that we measured EC values of 100–220 mS cm−1 in 2015 and 2018 at other springs (mostly sulfurous) emerging from the salt-dominated deposits further north within the Ghor Al-Haditha area (e.g. at the head of CM7 in Fig. 1b).

Although limited, there is some direct evidence of subsurface groundwater conduits. At the shoreward termination of CM1, subsurface conduits were found in 2014 (Fig. 8c) and have been noted for other channels to the north of the study area in Ghor Al-Haditha. These subsurface conduits tend to be associated with more competent evaporite horizons within the lacustrine sediments, which appear to form the roofs of the conduits, while the weaker clays are excavated beneath. Additionally, occasional “pipes” have been noticed in the base of sinkhole collapses in both the alluvial gravels and lacustrine deposits (Fig. 8a and b), implying that these materials are locally competent enough to sustain conduits, such as that inferred to have fed CM5 in 2015.

4.2 Geophysics

4.2.1 ERT and SP results at the head of active spring-fed channel CM5

As demonstrated in the previous section, the area around the head of stream channel CM5 has been a highly active zone of erosion and subsidence since its formation in 2012 (cf. Fig. 7; Al-Halbouni et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2019). These rapid geomorphological changes, occurring at the interface between alluvial cover and lacustrine sediments, made this area an obvious target for geophysical investigation of possible subsurface structures (i.e. cavities or conduits) in both materials. Consequently, near-surface geophysical surveys with the SP (array) and ERT (lines 3 and 4) methods were performed (Figs. 1 and 9).

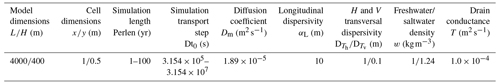

Using the PSO 2dD inversion method (cf. Sect. 3.3.1), we extracted and inverted data for five profiles when traversing the nearest-neighbour interpolated SP array (SP1–5; cf. Fig. 9a and d). The model misfit rms ranges from 5 % to 15 %, while the SP data error has been estimated in the field to be 4.5 %. Due to the 2D nature of the inversions, there is also a ∼ 10 m horizontal error in the location of each anomaly (in x–y space; cf. Fig. 9a). From these inversions, we derived the dimensions and orientations of the inclined “strips” of varying depths, widths and inclinations which best represent the modelled curves. The location and extent of these strips and the inferred flow directions are illustrated in Fig. 9e. The length of each strip corresponds to the half-width of the matching anomaly in Fig. 9d. The direction of water flow along a strip to produce the inverted anomalies is generally from minus (red) to plus (black). It should be emphasized that the modelled strips are by no means the only possible arrangements able to explain each SP anomaly, particularly in regard to the depth of the modelled strips: a long, deep strip may produce the same anomaly as a short, narrow one. For clarity, the results of profile SP3 have been moved to Appendix A, which also contains the detailed geometric and electric parameters of each inversion anomaly (Table A1).

The SP survey produced a complex dataset, the main anomalies of which are two large positive (red) patches with a maximum potential of ∂V = 50 mV, where δV = V−Vref (Vref being the potential at the reference electrode). These positive anomalies correspond to the pair of upflow anomalies (v) and (vi) along SP2 within alluvial gravel deposits which have subsided and fractured considerably with the formation of the uvala there. The “strip” anomalies are proportional in magnitude to the size of each patch. Additional upflow anomalies (i) and (iii) are present along SP1 with corresponding positive anomalies of ∂V ∼ 10 mV in the array and a horizontal flow anomaly (ii). Strip (iii) results in a long-wavelength anomaly from −10 to 10 mV in the second half of SP1. It appears to be flowing toward the locations of the formerly active spring s3. Other anomalies are recorded along SP4 and SP5, though the signals here are much weaker and noisier given the error margin, and hence the apparent “upslope” flow directions of some of these anomalies have to be treated carefully.

ERT lines 3 and 4 offer overlapping coverage with SP1 and SP5 and generally show decreasing resistivity with depth, stratified into two principal areas. The lower sections of both lines reveal an extremely low-resistivity layer (ρA = 1–5 Ωm) beneath more resistive zones. The top of this extremely low-resistivity layer lies at 8–10 m depth beneath the centre of ERT3, and in the case of ERT4 it forms a “wedge” in the north of the profile which is coincident at the surface with the lacustrine deposits of the former lake bed in the final section of the profile. The upper, more resistive zones of ERT3 and ERT4 show a range of resistivities from low values (ρA = 5–30 Ωm) indicated by light blue to light green colours, over middle values (ρA = 30–100 Ωm) indicated by dark green to yellow colours and high values (ρA = 100–500 Ωm) of reddish/violet colour. Patches of reddish/violet colours of very high resistivity (ρA > 500 Ωm) occur where the surface is highly fractured, with significant ground cracks. ERT4 shows a clear resistivity gradient from SSE to NNW also within the resistive zone. Although there is little apparent correlation between the SP flow anomalies and any significant resistivity anomalies in the ERT data, all the SP strips are modelled at depths above the very low-resistivity area within the upper, more resistive layers in a range of resistivity values between 15 and 100 Ωm.

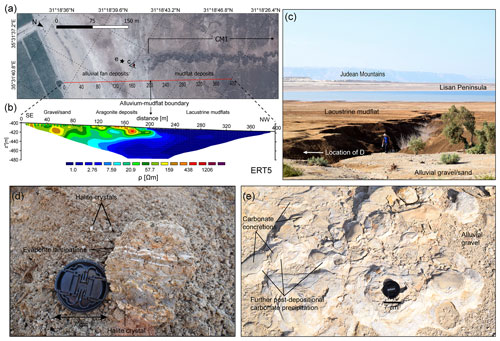

Figure 10ERT line 5 along the dry stream channel CM1 at the interface between alluvium and lacustrine sediments and associated surface manifestations. The survey used an inter-electrode distance of 5 m in a Wenner configuration. (a) Pleiades satellite image from April 2018 near canyon CM1 showing the profile location. (b) Electric resistivity distribution achieved by inversion of apparent resistivities. An rms of 7.5 % was achieved after six iterations. (c) Field photo from October 2018 looking NW along channel CM1, with contact between the alluvial fan deposits and the mudflat deposits of the former lake bed visible in the foreground near to the trees. Person for scale. The Lisan Peninsula and the Judean Mountains on the Dead Sea's western shore are visible in the background. (d) Hand specimen of the former lake-bed deposits from the bank of channel CM1; see part (c) for the location. Lens cap for scale. (e) Post-depositional carbonate concretions in the alluvial fan deposits; see part (a) for the location. Lens cap for scale. The minerals deposited are a mixture of aragonite, calcite, gypsum and clay minerals, all derived from the marls of the Lisan Formation. This degree of cementation is remarkable for the alluvium and is likely responsible for the elevated resistivity of the shallow subsurface at this location.

4.2.2 ERT results at inactive dry spring-fed channel CM1

To investigate the similarities and contrasts between presently and formerly active groundwater-fed stream channels, we performed an ERT traverse (line ERT5) which crosses the boundary between alluvium and lacustrine sediments next to channel CM1, which was dry in 2018 (although it was weakly active during field campaigns in the years 2014–2016). ERT5 reveals, similar to ERT lines 3 and 4, an extremely low-resistivity layer (ρA = 1–5 Ωm), which again coincides with surficial lacustrine mud deposits (Fig. 10). The ground above this layer in the south of the profile is more resistive, but the spatial distribution of these resistivities is not uniform, with a range of resistivities from low (ρA = 5–30 Ωm), indicated by light blue to light green colours, over middle (ρA = 30–100 Ωm) indicated by dark green to yellow colours and high values (ρA = 100–500 Ωm) by orange colours. Similar to ERT4, there is a clear resistivity gradient from south-east to north-west also within the resistive zone. Locally, very high-resistivity bodies (ρA > 500 Ωm) appearing as patches of reddish/violet colours in the profile can also be observed. The extremely low-resistivity layer is in horizontal contact with the more resistive zones in the centre (200 m) of the profile. At 150 m horizontal distance the depth to the low-resistivity layer is already 35 m. This zone of extremely low resistivity becomes more conductive towards the NW. Between 100 m and 140 m along the profile at depths below 10 m, there is a “tongue” of more resistive (green) material, which links gradually to the conductor beneath at around 30 m depth.

Field observations of the surface deposits around the ERT profile indicate that the differences in lithological properties between the lacustrine mud and the alluvial gravels are responsible for their contrasting responses to the injection of electrical current. The lacustrine mud exposed in the nearby stream channel walls (Fig. 10d) primarily comprises a light brown marl composed of carbonate and clay minerals, with some laminated horizons of evaporite deposits such as aragonite and gypsum (∼ 0.5 cm thick, white-coloured laminations). Idiomorphic halite crystals of up to 1 cm diameter also occur throughout this material. In contrast, the alluvial gravels and conglomerates are composed of mainly limestone and dolomite clasts with some basalt clasts (cf. El-Isa et al., 1995; Sawarieh et al., 2000), which are weakly to strongly cemented by minerals such as calcite, aragonite or gypsum. These minerals are dissolved and re-precipitated post-deposition as concretions on the clast surfaces and in the intervening pore spaces (cf. Bookman et al., 2004).

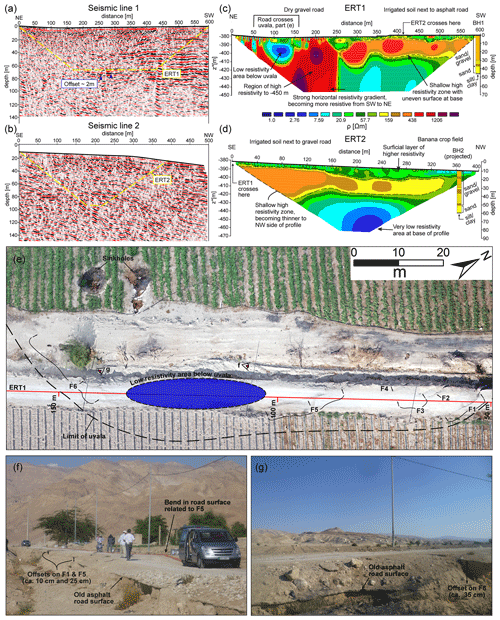

Figure 11Comparison of shear wave reflection and ERT profiles. (a) Seismic line 1 (modified after Polom et al., 2018b). The inserted yellow trapezoidal area marks the shape of ERT1. (b) Seismic line 2 (modified after Polom et al., 2018b). The inserted yellow trapezoidal area marks the shape of ERT2. (c) Electric resistivity distribution along profile ERT1 achieved by an inversion of apparent resistivities in a Wenner–Schlumberger roll-along configuration with an rms error of 11.9 % after nine iterations. (d) Electric resistivity distribution along profile ERT2 achieved by an inversion of apparent resistivities in a Wenner–Schlumberger configuration with an rms error of 3.8 % after six iterations. Borehole lithologies of BH1 and BH2 (projected) are derived from El-Isa et al. (1995) and recoloured from Polom et al. (2018). (e) Orthophoto image from 2014 of the damaged section of road crossing the uvala along ERT1. Six main fractures, F1–F6, are identified. (f) Field photo from 2014 of the subsided old asphalt road surface, which is offset on fractures F1 and F5 and locally overlain by the aggregate. (g) Field photo from 2014 of the offset of the old asphalt road surface on fracture F6.

4.2.3 Comparison of shear wave reflection seismics and ERT results in the main sinkhole area

To provide further context to the previous geophysical studies performed further inland in the study area (El-Isa et al., 1995; Sawarieh et al., 2000; Polom et al., 2018) and to investigate possible changes to the subsurface hydrology using electrical methods, we performed two new ERT surveys on the alluvial fan, at the southern edge of the uvala (for locations, see Fig. 1). ERT lines 1 and 2 are coincident with seismic profile lines 1 and 2 as reported by Polom et al. (2018), respectively (Fig. 11a–d). The seismic profilings were carried out along asphalt-topped roads; the ERT surveys were carried out on the soil next to these roads. Profile 1 transects the margin of a main uvala-like depression in this area, while profile 2 crosses a subtler and narrower zone of subsidence that extends south-west from the uvala. Numerous sinkholes formed adjacent to these profiles between 2002 and 2010, mainly within the uvala and the narrow subsidence zone (Watson et al., 2019); those around profile 2 were filled in by local farmers. Throughout the surveying time period (2014–2018), subsidence and related ground cracks (small faults or fissures) remained apparent along both roads, but especially around the point where the road crosses the uvala at the north-eastern end of ERT1 (Fig. 11e–g).

In general, both ERT profiles are characterized by a vertical resistivity profile consisting of multiple distinct layers, which agrees well with previous studies. A distinctive lobe with an uneven basal surface, defined across most of ERT2 and the south-western–central part of ERT1, is characterized by high (ρA = 100–500 Ωm) resistivity values in the upper 30–40 m of the subsurface. This is underlain by a zone of low (ρA = 5–30 Ωm) to extremely low (ρA = 1–5 Ωm) resistivity values at depths below 40–50 m. The high-resistivity layer is overlain by a thin (5–10 m thick) layer of moderate (ρA = 30–100 Ωm) resistivity, corresponding to irrigated topsoil. This apparent stratification is in broad agreement with the borehole results of El-Isa et al. (1995): the middle high-resistivity layer corresponds to interbedded sands and coarser gravels, below lower resistivities correspond to sand and even lower resistivities represent the silt and clay layers detected only at the bases of the boreholes. The seismic data in these areas consist of reflectors dipping gently to the north-west, representing the top sets of the underlying alluvial fan system (Polom et al., 2018). Additionally, the resistivity values presented for ERT line 5 of Alrshdan (2012), ρA = 40–200 Ωm, are largely similar to those of the uppermost 25 m of ERT1. Similar to the results of ERT4 and ERT5 near the mudflat, there is a resistivity gradient from south-east (400 Ωm) to north-west (60 Ωm) visible in ERT2.

A clear link between subsurface, low-resistivity anomalies in the ERT data and surface subsidence features is imaged in the north-eastern section of ERT1, where the profile intersects the southern limits of the uvala. A striking area of reduced resistivities is apparent, with its centre around 120 m along-profile at around 20 m depth. These low resistivities (ρA < 10 Ωm) form a “blob” around 50 m wide and 20 m high, with a rapid gradient at its edge to a surrounding area of greatly elevated (ρA > 500 Ωm) resistivity. This region of elevated resistivity continues to the base of the profile here (Fig. 11c). The corresponding part of the seismic section consists of strongly scattered, chaotic reflection patterns. The low-resistivity anomaly is directly beneath the area of maximum subsidence along the road, as shown in the aerial and field photos in Fig. 11e–g. A smaller, vertically elongate low-resistivity anomaly 50 m along ERT1 is also visible. This anomaly may be corroborated by ERT data from line 4 of Alrshdan (2012), which overlaps the north-eastern end of ERT1 and shows a similar low-resistivity (ρA < < 10 Ωm) approximately 10 m diameter area at a similar depth (< 10 m).

Another significant anomaly in ERT1 is the strong horizontal resistivity gradient between the previously mentioned region of high (ρA > 500 Ωm) resistivity to the north-east and a lower (ρA = 10–20 Ωm) region to the south-west, around 250 m along-profile (Fig. 11c). This linear feature is also visible in the seismic section: an offset of ∼ 2 m between a strong reflector at ∼ 80 m depth (just below the vertical extent of ERT1), downthrowing to the north-east, is marked by blue arrows around 260 m along-profile. The VES survey results of El-Isa et al. (1995) in this area also found evidence of a vertical disturbance of this nature, which they attribute to the presence of a fault.

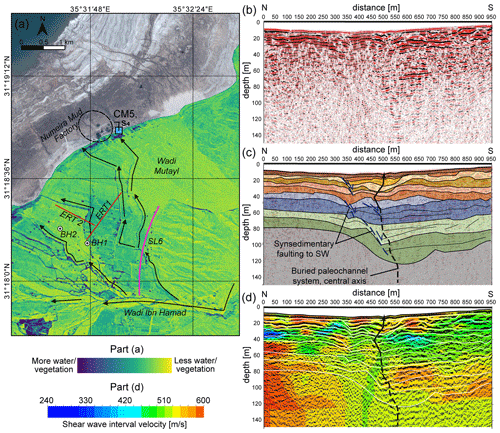

Figure 12Evidence of water flow in sediments of the Wadi Ibn Hamad alluvial fan as deduced from aerial photos and reflection seismic profile 6 connected to stream channel CM5. (a) Coloured Corona satellite image from 1970 overlain on a 2018 Pleiades satellite image, depicting the former surface channel network in the alluvial fan deposits. Water content and vegetation appear in blue (modified after Al-Halbouni et al., 2017). Flow directions in the areas of elevated water content, as determined from the hydraulic gradient toward the Dead Sea, are highlighted by arrows to the right of the flow pathways. (b) Shear wave reflection seismic profile 6 along the Amman–Aqaba highway near Ghor Al-Haditha (cf. Fig. 2). (c) Structural interpretation of seismic profile 6; analysis is described in Polom et al. (2018). Structures associated with development of a former channel system are recognized in the central part. (d) Shear wave interval velocity overlain on reflection profile 6.

4.2.4 Shear wave reflection seismics along a section of the Amman–Aqaba highway

The hydrology of the Wadi Ibn Hamad alluvial fan has evolved significantly since the inception of base-level fall at the Dead Sea in the 1960s. This is highlighted in Fig. 12a, which shows the 1970 configuration of the wadi's delta system. The presence of vegetation and water at the surface (represented by blue colours on the map) highlights numerous distributary channels for water emanating from the wadi, two of which diverge from a fork a few hundred metres from the fan apex and run from there toward the former Numeira mud factory site (Al-Halbouni et al., 2017). The north-eastern end of ERT1 appears to cross one of these old channels, near the low-resistivity anomaly detected in the subsurface there (cf. Fig. 11c). After 1970, this surface water distributary system was significantly modified by the excavation of a single, straight exit channel for the Wadi Ibn Hamad and by the development of agricultural fields in a grid-like arrangement (Fig. 1b). An extensive area of dense vegetation directly at the former Dead Sea shoreline is nonetheless indicative of a sustained source of sub-surface freshwater around the Numeira mud factory site.

Seismic profile 6 runs along the Amman–Aqaba highway and crosses this former distributary channel close to its fork (Fig. 12a). The seismic section in Fig. 12b reveals a vertically extensive paleochannel system in the superficial aquifer as highlighted in Fig. 12c, with the first interpreted horizons occurring at around 20 m depth and the deepest at around 120 m depth. The derived velocities between 240 and 600 ms−1 for these alluvial gravels (Fig. 12d) represent differing degrees of sediment compaction and/or cementation (cf. Polom et al., 2018). The axis of this interpreted palaeochannel system coincides with intersection of the 1970 distributary channel with the profile line. Synsedimentary faulting is visible to the north of the central axis of the paleochannel with downthrow to the south-west.

Figure 13Water table estimation from GPR. (a) GPR profile 1 running NE–SW parallel to ERT1 reveals a horizontal reflector between 400 and 500 ns two-way travel time (∼ 30–34 m depth below the surface). Note the gap between 190 and 210 m which is due to a surface artificial concrete channel. (b) GPR profile 2 running NW–SE along line ERT2 revealing a similar reflector at around 500 ns two-way travel time (∼ 38 m depth below the surface). Note that GPR profiles have been topography corrected via linear interpolation only; i.e. the depression is not shown in GPR1. Characteristic reflections have been marked by arrows. (c) GPR profile 2 electromagnetic wave velocity distribution. A characteristic drop in wave velocity is seen at the interface between the saturated and unsaturated zones.

4.2.5 Water table inferred from GPR