the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Evaluating Long-Term Effectiveness of Managed Aquifer Recharge for Groundwater Recovery and Nitrate Mitigation in an Overexploited Aquifer System

Yuguang Zhu

Zhilin Guo

Sichen Wan

Kewei Chen

Yushan Wang

Zhenzhong Zeng

Huizhong Shen

Jianhuai Ye

Chunmiao Zheng

Managed aquifer recharge (MAR) has been widely recognized as an effective strategy for groundwater restoration and has been implemented globally. In the North China Plain, over-extraction of groundwater has led to a continuous decline in water levels, forming one of the world's most significant groundwater depressions. Recent riverine MAR operations have shown significant local groundwater recovery; however, the long-term regional fate and spatial evolution of nitrate remain poorly quantified. In particular, it remains challenging to assess how geological heterogeneity interacts with biogeochemical processes to control remediation efficacy. Most existing studies rely on short-term field monitoring and emphasize localized responses. This study, focusing on the Xiong'an depression area, develops a coupled flow and multi-component reactive transport model to evaluate the long-term impacts of MAR on groundwater recovery and the spatiotemporal evolution of water quality. The results indicate that MAR leads to a basin-wide mean groundwater level rise of 1.11 m, with a maximum increase of 7.5 m near the river. Nitrate reduction is dominated by physical dilution (∼ 91 %) rather than denitrification (∼ 9 %).Furthermore, geological heterogeneity governs the spatial variability of water quality evolution by channelling flow through preferential pathways, which creates localized reduction hotspots, despite having a minimal impact on the total nitrate mass removal. These findings highlight the dual hydrological and geochemical benefits of sustained MAR and provide quantitative insights for optimizing large-scale recharge strategies in overexploited aquifer systems.

- Article

(7303 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(530 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Groundwater is a vital global freshwater resource, playing a crucial role in drinking water supply, agricultural irrigation, and industrial development, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions (Kuang et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2024). However, rising demands from population growth, agricultural intensification, and urban expansion have led to unsustainable extraction, with agricultural irrigation alone consuming over 40 % of global groundwater withdrawals (Guo et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016; Gong et al., 2018; Mukherjee et al., 2021). The long-term over-extraction has caused widespread aquifer depletion and significant declines in groundwater levels, leading to severe ecological and environmental consequences, such as seawater intrusion, river desiccation, and land subsidence (Peters et al., 2022; Escriva-Bou et al., 2020; Levy et al., 2021). Amid these challenges, groundwater quality degradation, specially salinization and nitrate pollution, has become a pressing concern in many arid regions (Pauloo et al., 2021; Zhan et al., 2025). These issues are particularly acute in agricultural areas such as the North China Plain (NCP), where the largest groundwater depression in the world has developed since the 1970s (Zheng and Guo, 2022; Wu et al., 2024), resulting in severe ecological deficits and a negative groundwater balance (Zhao et al., 2019; Su et al., 2021).

Managed aquifer recharge (MAR) has been widely adopted as a strategy to mitigate groundwater depletion. MAR methods, including enhanced infiltration, bank filtration, and well injection, primarily use surface water sources to replenish aquifers (Bagheri-Gavkosh et al., 2021; Zhan et al., 2024), with infiltration-based approaches being most common (Sprenger et al., 2017). Global analyses suggest that MAR has contributed to measurable groundwater restoration in about 16 % of stressed aquifer regions (Jasechko et al., 2024). However, alongside hydraulic benefits, MAR can trigger geochemical changes that influence groundwater quality (Guo et al., 2023a, b). For example, mineral dissolution during recharge has been shown to increase fluoride and phosphate (Schafer et al., 2018), while oxidized recharge water has induced pyrite oxidation, mobilizing metals (Vergara-Saez et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2023b). Such outcomes underscore that MAR-driven water quality changes are strongly dependent on aquifer mineralogy, recharge chemistry, and biogeochemical conditions.

A critical but less understood dimension is the role of aquifer heterogeneity and biochemical reactions in controlling water quality during MAR. Preferential flow paths in heterogeneous media govern solute transport and reaction zones (Zheng and Gorelick, 2003; Chen et al., 2024), yet regional-scale assessments explicitly integrating these effects remain scarce. While soil-scale and laboratory experiments have quantified nitrogen adsorption, nitrification, and denitrification (Mekala and Nambi, 2016; Zhan et al., 2024), they often omit microbial degradation of organic matter and carbon–nitrogen coupling. Previous studies often simplify denitrification as a first-order decay process, thereby neglecting the kinetic coupling between nitrate reduction rates and the availability of electron donors. Similarly, one-dimensional or small-scale numerical models (Liang et al., 2024) capture aspects of nitrogen transformation under MAR but cannot represent complex groundwater-surface water interactions or long-term cumulative pollution risks. Evidence indicates that dilution effects dominate MAR-induced nitrate decreases (Guo et al., 2023a), but the broader role of heterogeneity and biogeochemical feedback in governing nitrate persistence or removal at regional scales remains unresolved.

Therefore, this study aims to address these gaps by developing a numerical modeling framework to evaluate the long-term impacts of sustained MAR implementation on groundwater recovery and nitrate dynamics in the groundwater depression area. Specifically, we would answer two main questions: (1) How does MAR affect groundwater recovery in a severely depleted aquifer system? (2) How do heterogeneity and biogeochemical reactions interact with MAR to control the spatiotemporal evolution of nitrate concentrations in groundwater?

This paper is organized as follows. First, we describe the hydrogeological setting, water budget, and groundwater quality of the study area. We then present and justify the modeling framework (calibrated flow, reactive transport for nitrate, and T-PROGS–based heterogeneity), followed by the scenario results. Finally, we discuss management implications for MAR, key limitations, and the transferability of the approach to other overexploited aquifer systems.

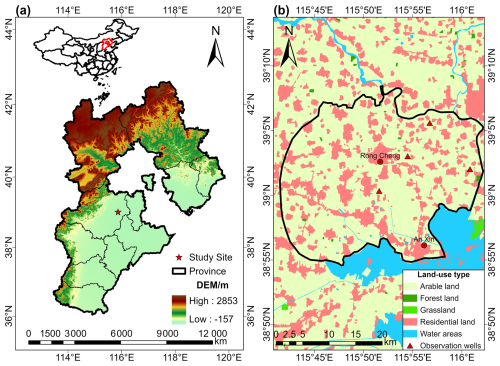

2.1 Study site

The study area is located in the central Xiong'an New Area, Hebei Province, covering ∼ 536 km2. It is bounded by the Nanjuma River (northeast), Baigouyin River Diversion Canal (east), Baiyangdian Lake (south), Dingxing County (northwest), and a shallow groundwater depression cone (west) (Fig. 1). The region lies at the center of the NCP, characterized by flat alluvial plains (average elevation 10–15 m) and Quaternary deposits ranging from 10 to 500 m in thickness. Groundwater depth ranges from 5 to 30 m. Groundwater in the Xiong'an New Area occurs in Quaternary alluvial–pluvial unconsolidated deposits forming four aquifer groups (I–IV). We focus on the shallow system (Groups I–II) and the unsaturated zone. Land use is dominated by arable land, with construction land as a secondary use, and some grassland in certain regions (Fig. 1). The study area has a warm temperate humid monsoon climate, with mean annual precipitation of 400–501 mm, more than 75 % of which occurs between June and September.

Groundwater recharge sources mainly include infiltration from atmospheric precipitation, lateral recharge, river infiltration and irrigation return, while pumping is the dominant discharge. Long-term over-extraction has formed a distinct groundwater depression funnel, typical of the NCP. Since 2018, artificial recharge has been implemented through diversion of South-to-North Water Transfer Project inflows into local rivers, aiming to restore groundwater levels and secure long-term water supply for Xiong'an.

Groundwater and river water samples were previously collected to characterize water quality and chemistry and measure chemical parameters (Chen, 2022). Ca2+ in groundwater is between 9.075 × 10−4 and 2.7 × 10−3 mol L−1, primarily from the dissolution of calcite and gypsum. HCO concentration of groundwater was from 3.1 × 10−3 to 8.92 × 10−3 mol L−1 and SO concentration of groundwater was from 3.13 × 10−4 to 2.41 × 10−3 mol L−1. At some sampling points, nitrate concentrations reached 1.94 × 10−3 mol L−1, exceeding the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) drinking water NO standard of 8.87 × 10−4 mol L−1.

Figure 1Study Area Location and Land Use Distribution. (a) Geographic location of the study site in China, showing the elevation data (DEM) with high and low points. (b) Land-use map of Rongcheng, illustrating the distribution of arable land, forest land, grassland, residential land, water areas, and observation wells.

2.2 Numerical model

2.2.1 Governing equation

Groundwater flow and reactive transport under MAR were simulated using PFLOTRAN (Hammond et al., 2014), a massively parallel 3D reactive transport model. Variably saturated flow is described by the Richards equation:

where φ is porosity; s is saturation; η is the mole water density [kmol m−3]; q is Darcy's flow velocity (positive: upwelling) [m s−1]; Qw is the source/sink term for mass transport [kmol m−3 s−1]; k is intrinsic permeability [m2]; ρw is the water density [kg m−3]; μw is the water viscosity [kg m−1 s−1]; g is the gravitational constant [m s−2]; P is pressure [Pa]; z is the vertical component of position vector (positive: upwelling) [m].

The governing equation for multi-component reactive transport in single-phase flow is,

where i represents the ith primary species hereinafter, Ψi is the total concentration [mol L−1], Ωi is the total flux [mol L−1 s−1]. Qi is the source/sink term [mol L−1 s−1], vim is the stoichiometry coefficient of ith primary species in mineral m, Im is the mineral precipitation/dissolution rate based on transition state rate [mol L−1 s−1], and Si is the sorbed concentration [mol L−1].

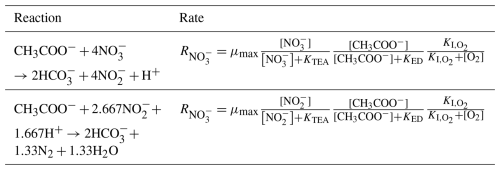

Denitrification was modeled as a two-step reduction (NO → NO → N2) (Table 1), with acetate (CH3COO−) as the electron donor, following Michaelis–Menten kinetics (Chen et al., 2023a, 2025). Although denitrification inherently involves complex enzymatic pathways and intermediate products, a simplified two-step reduction scheme was adopted in this study based on the specific hydrogeological context of the Xiong'an New Area. First, the shallow aquifer system is characterized by predominantly oxidizing conditions, as evidenced by high dissolved oxygen concentrations and a scarcity of organic electron donors (Li et al., 2023). Under such biogeochemical constraints, the overall reaction rate is governed primarily by the availability of electron donors and the inhibition threshold of dissolved oxygen, rather than by the transformation kinetics of intermediate species. Reflecting this, the kinetic formulation in Eq. (5) incorporates dual-Monod terms to explicitly represent donor limitation and oxygen inhibition, effectively capturing the rate-limiting steps. Second, the regional-scale and long-term nature of the simulation (536 km2) necessitates a balance between mechanistic detail and computational feasibility. The two-step reduction scheme ensures the conservation of nitrogen mass balance while maintaining numerical efficiency, avoiding the excessive parameter uncertainty associated with complex multi-step reaction networks. This approach aligns with established practices in regional reactive transport modeling(Guo et al., 2023a; Karlović et al., 2022; Jin et al., 2024).

where μmax is the rate constant [mol L−1 s−1]; CED, CTEA and CI represent the concentrations of the electron donor (ED), terminal electron acceptor (TEA), and inhibitor (I) [mol L−1]; KED, KTEA and KI are the half-saturation constants for the electron donor, acceptor, and inhibitor [mol L−1].

It is important to note that an explicit dynamic microbial biomass pool was not simulated due to the lack of spatial data for microbial parameters at the regional scale. Instead, a quasi-steady-state biomass concentration is assumed to be present in the aquifer sediments. Therefore, the effect of biomass abundance is implicitly incorporated into the effective rate constant (μmax). This simplification avoids the high parametric uncertainty associated with unconstrained biological parameters (Schäfer Rodrigues Silva et al., 2020) and aligns with theoretical frameworks for effective kinetics in heterogeneous media (Le Traon et al., 2021). Regarding the final term in Eq. (5), it represents the inhibited effect controlled by thermodynamically more favorable electron acceptors. In the context of denitrification modeled here, the process is strictly anaerobic and is inhibited by dissolved oxygen (Appelo and Postma, 2005). Therefore, CI represents the concentration of dissolved oxygen. This term functions as a kinetic switch, reducing the reaction rate (R) effectively to zero when dissolved oxygen concentrations are high, reflecting the preferential utilization of oxygen over nitrate by facultative anaerobes.The parameters for reactive transport are provided in Table S1.

2.2.2 Model setup

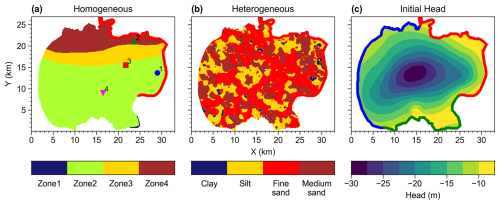

The model domain (33 km × 26.9 km × 135 m) was discretized into 100 m horizontal grids and three vertical layers: 15, 40, and 80 m, representing the vadose zone, the phreatic aquifer, and the underlying unit, respectively. A grid-resolution sensitivity test was conducted to ensure the numerical robustness of the groundwater flow simulation, based on which the 100 m horizontal grid spacing was adopted for the full set of simulations. The permeability coefficients of the aquifer were determined through pumping tests. Using hydrological and geological data from Hebei Province, lithofacies paleogeographic features, and previous parameter zoning maps, a permeability coefficient zoning map (Fig. 2a) was generated, providing the baseline scenario (homogeneous fields) for the flow model (Table S2). Additionally, a fully heterogeneous scenario was simulated to evaluate impact of heterogeneity, especially preferential flow path on the performance of MAR and its effects on groundwater quality. Four lithofacies: clay, silt, fine sand, and medium-to-coarse sand were identified by 14 borehole lithologies (Fig. S1) and used to conditionally generate heterogeneous field using Transition Probability Geostatistical Software (T-PROGS), which is based on transition probability–Markov chain model to generate 3D realizations of random fields (Carle and Fogg, 1997). To represent structural uncertainty, we generated 20 TPROGS-conditioned heterogeneous realizations and simulated each realization independently; results were summarized by the ensemble mean across realizations. One representative heterogeneous realization is shown (Fig. 2b); the full parameter list is provided in the Supplementary material (Table S3). The unsaturated zone was modeled using the van Genuchten–Mualem model to describe the relationship between soil water content and soil water potential, calculating both saturation and relative permeability.

Figure 2Model parameterization and Initial condition. (a) Permeability zoning for the baseline (homogeneous) field. (b) Lithofacies-conditioned heterogeneous permeability field generated with TPROGS (one realization shown). (c) Spatial Distribution of Initial Head (2017).

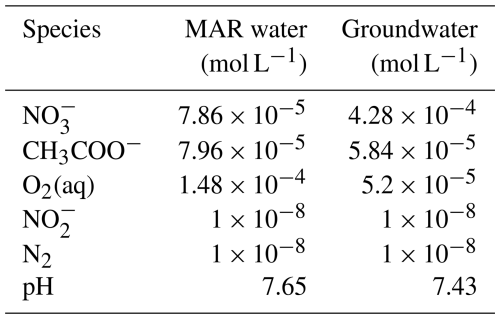

The flow boundary conditions are assigned by incorporating the physical conditions on each side. The upper boundary is set as a flow boundary driven by daily precipitation. Additionally, since the area is agricultural, there are high concentrations of nitrates in the surface layer from irrigation water. The bottom bounded by bedrock is set as a no flow boundary. The western boundary coincides with the groundwater-depression margin and is imposed as a specified-head (Dirichlet) boundary using the initial potentiometric surface. The southern boundary, corresponding to Baiyangdian Lake, is assigned a constant head of 6.5 m. The northern and eastern boundaries are designated as recharge flow boundaries, with fluxes determined from monitoring reports (Jin et al., 2024). The measured groundwater flow field in 2017 was adopted as the initial condition for the model (Fig. 2c). Initial and boundary solute conditions for reactive transport were derived from measured chemical conditions of recharge water and groundwater (Table 2).

The artificial recharge scheme is designed based on the field measurements of flow data from the Xingaifang station during 2018–2019. The recharge period is defined as August to December each year. The simulation assumes that the recharge duration, location, and infiltration efficiency remain constant over the prediction period, and the evolution of groundwater levels and solute concentrations is projected until 2035.

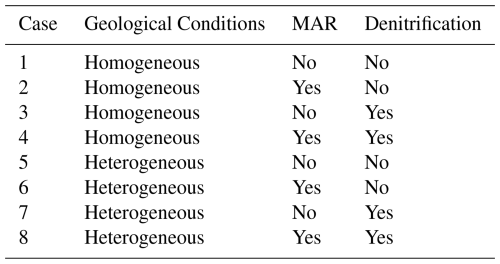

2.3 Simulation cases

Eight simulation scenarios (Table 3) were designed to evaluate the impact of geological structural conditions, artificial recharge measures, and denitrification processes on nitrate concentration dynamics in groundwater. In the groundwater flow simulation, a homogeneous case was established by dividing the model domain into four hydrogeologic zones based on local geological records (Li et al., 2023), with the hydraulic conductivity of each zone determined from pumping test results (Xu, 2022) to represent the regional hydraulic properties of the study area. To investigate the influence of stratigraphic heterogeneity on solute migration, reactive transport simulations were performed for 20 heterogeneous realizations and the ensemble-averaged results were compared with those from the homogeneous case.

Scenario combinations are constructed by considering the presence or absence of artificial recharge, denitrification, and geological heterogeneity, thereby enabling a comprehensive assessment of individual and interactive effects. To assess the impact of artificial recharge on regional groundwater level recovery, Case 1 and Case 2 are compared, while the role of artificial recharge in nitrate removal is analyzed by comparing Case 1 with Case 2 and Case 5 with Case 6 under different geological structures. The denitrification contribution is analyzed by comparing Case 1 with Case 3 and Case 5 with Case 7 to quantify the role of denitrification in nitrate reduction. The synergistic effect is discussed by comparing Case 1 with Case 4 and Case 5 with Case 8 to assess the combined impact of artificial recharge and denitrification reactions and their additive or antagonistic effects.

To reduce bias caused by concentration magnitude difference among scenarios and to highlight relative changes, the concentration differences (ΔC) for each scenario are logarithmically transformed. This transformation helps visualize the distribution patterns of high and low variation zones in the spatial distribution analysis.

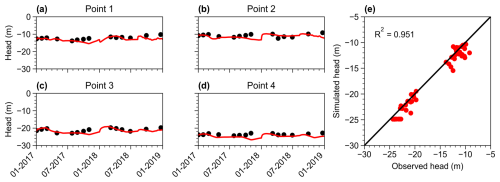

3.1 Model calibration

To verify the model's reliability, simulated groundwater levels were compared against observations from four observation wells (Points 1–4) over 2017–2019 (Fig. 3a–d). The results show that the simulated water level trends at the four observation points are generally consistent with the measured values (R2=0.95) and accurately reflect the dynamic changes in water levels during both the recharge and non-recharge periods. In particular, during the first recharge phase from August to December 2018, rise in water levels was observed at Point 1 and Point 2, which are located near the recharge area, and the model was able to accurately capture this sudden increase. In contrast, the more muted responses at distal wells (Points 3 and 4) were also reproduced. Additionally, a domain-wide groundwater budget was computed, with major inflow and outflow components summarized in the Supplementary Information (Table S4). Collectively, these results indicate that the constructed groundwater flow model reliably represents the spatiotemporal variations in groundwater levels under recharge and non-recharge conditions, providing a robust hydrodynamic basis for solute transport analysis (Fig. 3e).

3.2 Impact of MAR on groundwater levels

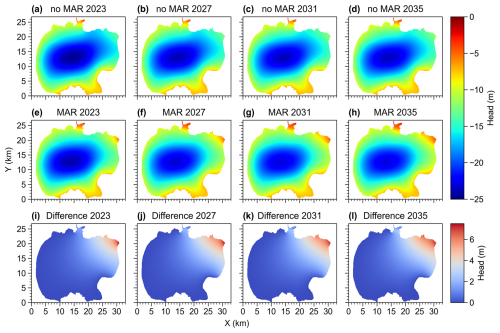

We assess basin-scale groundwater level responses to MAR during 2023–2035 by comparing simulations with and without recharge (Fig. 4). Without MAR, the cone of depression persists with limited natural recovery (Fig. 4a–d). MAR systematically elevates water levels, weakens the depression, and propagates higher heads inward from the river margins (Fig. 4e–h).The corresponding difference field (Δh, defined as headMAR − headno MAR), shows a persistent high-Δh corridor along the northeastern river margin in all periods (Fig. 4i–l), with maximum rises up to 7.5 m and a mean gain of 1.11 m. Influence extends ∼ 5 km from the recharge reach, decaying toward the depression center where recovery remains limited. From January 2023 to January 2031, the high-Δh belt expands slightly inland and the gradient relaxes (Fig. 4i–k); by January 2035 (Fig. 4l), the pattern stabilizes with only modest additional propagation. Taken together, MAR elevates heads most strongly near the river and transmits effects inward with distance- and connectivity-controlled attenuation, consistent with the area's permeability structure (Fig. 4). A quantitative zonal analysis further confirms this control: by 2035, Zone 1 acts as a hydraulic barrier with 100 % of cells showing minimal recovery (Δh<1 m). In contrast, the high permeability corridors facilitate significant recovery, with Zone 3 showing extensive coverage (64 % cells > 1 m) and Zone 4 achieving the highest mean rise (∼ 3.18 m) and peak values (∼ 7.5 m) (Fig. S2). This demonstrates that strong MAR benefits are spatially confined to conductive pathways (Zones 3–4) rather than being uniformly distributed.

Figure 4Spatial distribution of groundwater levels and changes with and without MAR. (a–d) Spatial distribution of groundwater levels without MAR. (e–h) Spatial distribution of groundwater levels with MAR. (i–l) Spatial distribution of groundwater head differences.

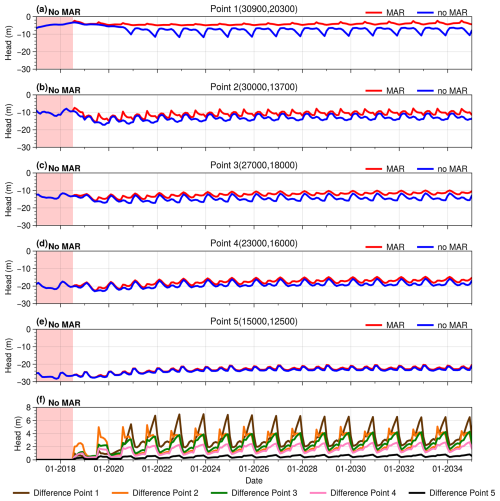

Time-series head from five monitoring points (Fig. S3) further illustrate distance- and permeability-dependent responses. Points 1 and 2 are located near the recharge area, with Point 1 in a high-permeability zone and Point 2 in a low-permeability zone. Points 3 and 4 are progressively farther from the recharge location, with the distance between Point 4 and the recharge location being approximately twice that of Point 3. Point 5 lies within the cone of depression. Near the river, Point 1 (high-permeability) and Point 2 (low-permeability) exhibit rapid onsets during recharge windows and persistent head gains thereafter. Although the two sites respond nearly synchronously, their cumulative water-level rise varies with permeability: Point 1 rises by ∼ 4–7 m, while Point 2 increases by ∼ 3–5 m across the projection horizon (Fig. 5a, b). Superimposed on the step-like elevation is a distinct seasonal cycle – peaks that coincide with recharge pulses and troughs that reflect background abstraction – indicating that MAR augments, rather than overrides, the natural intra-annual variability.

Figure 5Groundwater level changes and differences at observation points; (a–e) time series of water level changes at observation points (Point 1 to Point 5) with and without MAR; (f) differences in water levels (MAR vs Without MAR) for all observation points.

With increasing distance from the river, the MAR signal becomes weaker and arrives later. Inland points (Points 3 and 4) exhibit delayed and dampened responses (∼ 2–4 m and ∼ 1–2 m, respectively), while the depression-center well (Point 5) shows only minor gains. Seasonal cycles remain evident at all sites, with recharge pulses superimposed on background abstraction. The amplitude hierarchy (Point 1>2>3>4>5) is consistent across years, demonstrating that permeability controls recovery magnitude near the river, while distance and connectivity govern inland attenuation.

3.3 Individual effect of MAR and Denitrification on nitrate distribution

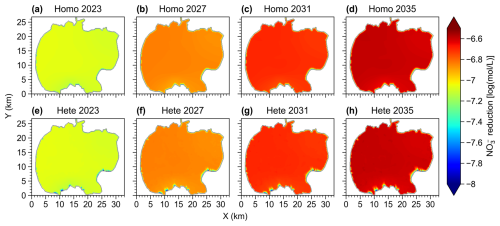

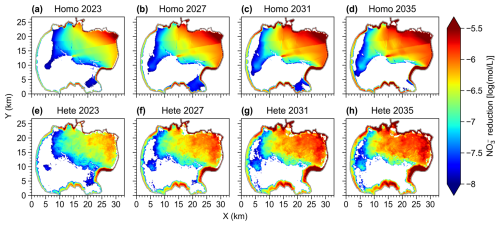

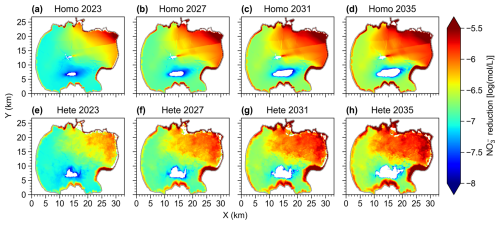

Under homogeneous geology, MAR induces a smooth and continuous nitrate reduction pattern, strongest along the river corridor and extending inland over time, (Fig. 6a–d). From 2023 to 2035, the high-reduction belt expands landward while preserving strong spatial continuity and year-to-year persistence. By 2035, cells exhibiting a discernible reduction cover 67.85 % of terrestrial model cells, indicating that in homogeneous media the recharge signal propagates rapidly and relatively uniformly and sustains a basin-scale decline in nitrate.

Figure 6Nitrate reduction due to MAR (without reaction). (a–d) Homogeneous geology, 2023/2027/2031/2035; (e–h) heterogeneous geology, same periods.

In contrast, under heterogeneous conditions, the same reduction appears, but it is strongly patchy and anisotropic (Fig. 6e–h). High-permeability corridors form reduction hotspots, while low-permeability and poorly connected zones show weaker or negligible changes. Inland expansion is faster and more fragmented compared to the homogeneous case with 73.43 % of cells affected by 2035, 5.58 % higher than under homogeneous conditions, and pronounced reductions remain concentrated within ∼ 15 km of the river. This contrast reflects permeability-controlled flow partitioning and residence times that high-permeability pathways accelerate dilution and flushing, whereas low-permeability zones restrict response.

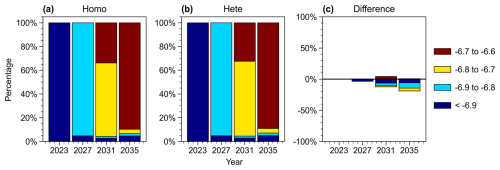

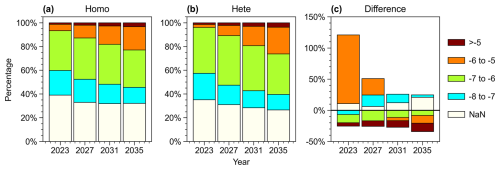

The spatial responses can be summarized by area-contribution analysis of signed log-difference classes relative to the baseline (Fig. 7a–c). Negative values indicate decreases in nitrate concentration; within this negative range, values closer to zero represent larger absolute decreases. The response classes correspond to orders of magnitude: −8 to −7 (very small decrease), −7 to −6 (small), −6 to −5 (moderate to large), and > −5 (the most distinct decreases, at least on the order of 10−5); while the absolute magnitude (10−5) appears minor, it represents the primary zones of cumulative mass removal in the system. Cells labeled NaN lie below the magnitude threshold. Both homogeneous and heterogeneous settings show a growing footprint of meaningfully responding cells (non-NaN) and a shift toward stronger response classes, but heterogeneity case achieves greater magnitude. In the homogeneous field (Fig. 7a), the non-responding cells (NaN) declines from 39.0 % (2023) to 32.2 % (2035), the moderate–large class (−6 to −5) expands from 5.4 % to 19.6 %, and the strongest class (> −5) from 1.28 % to 3.28 %, while the small-reduction class (−7 to −6) remains modal at roughly 31–33 %. In the heterogeneous field (Fig. 7b), the same pattern holds, but the magnitude is enhanced: NaN decreases from 35.2 % to 26.57 %, and the expansions into −6 to −5 and > −5 reach 22.43 % and 3.79 %, respectively, bigger gains than in the homogeneous case (Fig. 7c). Thus, MAR consistently expands the footprint of nitrate reductions, while heterogeneity enhances the intensity of reductions but weakens their spatial uniformity. To isolate the role of denitrification, recharge was disabled and only the reaction process was simulated. Under homogeneous geology, denitrification yields a spatially continuous nitrate decreaseacross the basin (Fig. 8a–d), which intensifies over time but retains a uniform pattern, indicating reaction control. Under heterogeneous geology, the reduction remains domain-wide but slightly non-uniform, with near-river high-permeability zones showing weaker declines due to shorter residence times that limit reaction (Fig. 8e–h).

Figure 7Area-contribution analysis of concentration log-difference response classes under MAR. (a) Homogeneous; (b) heterogeneous; (c) relative difference = (homogeneous − heterogeneous) heterogeneous. Bars show area fractions at four snapshots (2023, 2027, 2031, 2035).

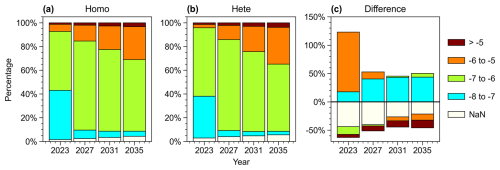

Area-contribution analysis confirms this systematic trend (Fig. 9a–c). Both homogeneous (Fig. 9a) and heterogeneous (Fig. 9b) fields show a coherent order-of-magnitude shift and remain closely aligned in magnitude. The domain evolves from being entirely < −6.9 in 2023 (100 %) to being dominated by −6.7 to −6.6 in 2035, accounting for ∼ 90.0 % under the homogeneous field and 89.03 % under the heterogeneous field, with −6.9 to −6.8 prevailing in 2027 (∼ 95 %). This trajectory indicates a systematic amplification and narrowing of absolute decreases toward the 10−6.7–10−6.6 range and shows limited sensitivity to permeability heterogeneity overall. Notably, the overall removal efficiency (Fig. 9c) is ∼ 1 % lower under the heterogeneous setting, consistent with its slightly smaller share in the strongest response classes. The modeled negligible and uniform denitrification is fundamentally driven by the hydrogeochemical regime of the study site. Field data (Table 2) indicates that the aquifer is generally oxidizing and carbon-limited. This outcome validates the suitability of the adopted two-step reduction scheme (Eq. 5), which effectively captures the suppression of denitrification rates under such donor-poor and oxidizing conditions. Under such conditions, the reaction kinetics are globally suppressed by oxygen inhibition and electron donor starvation. Consequently, the influence of physical heterogeneity (i.e., variability in residence time) becomes secondary to this overwhelming chemical limitation. Even in zones with long residence times, the reaction rates remain low due to the lack of favorable redox conditions, resulting in a spatially uniform distribution of minimal denitrification.

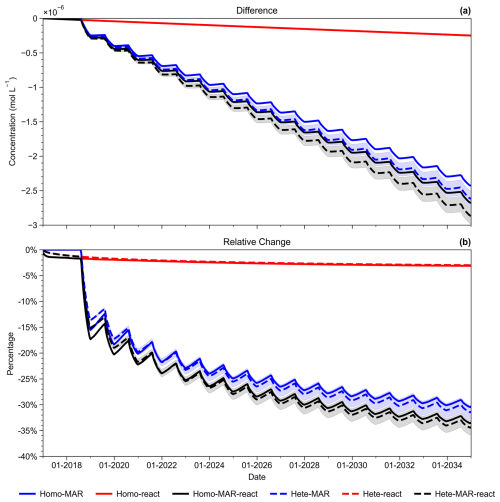

3.4 Combined effect of MAR and Denitrification with Spatial Mean Analysis

When MAR and denitrification act together, nitrate declines basin-wide relative to the no-recharge, no-reaction baseline (Fig. 10). Under homogeneous geology (Fig. 10a–d), the combined effect produces a smooth near-river belt that expands inland from 2023 to 2035, yielding a broad footprint with 95.58 % of terrestrial cells affected. The spatial pattern indicates recharge-driven dilution dominates within ∼ 5 km of river, where concentrations drop rapidly, while denitrification governs the slower decay in the 5–15 km inland zone. Under heterogeneous geology (Fig. 10e–h), the combined effect also lowers nitrate but forms a patchy, anisotropic mosaic due to preferential flow along high-permeability corridors. The overall affected fraction is 94.38 %, and spatial heterogeneity is more evident than in the homogeneous case, with stronger contrasts between well-connected and poorly connected regions.

Area-class analysis (Fig. 11a–c) shows that the combined forcing yields the largest and most persistent expansion of favorable classes in both settings, with the heterogeneity case advancing further. Under the homogeneous field (Fig. 11a), the small-reduction band (−7 to −6) increases from 49.8 % in 2023 to 60.3 % in 2035, the moderate–large band (−6 to −5) from 6.0 % to 27.7 %, and the strongest band (> −5) from 1.28 % to 3.31 %. In the heterogeneous field (Fig. 11b), the small-reduction band is nearly unchanged, while the moderate–large (2.9 % to 31.0 %) and strongest (1.35 % to 3.83 %) bands grow more than in the homogeneous case. Unlike the MAR-only runs, the heterogeneous setting also retains a larger share of non-responding cells (NaN increasing from 2.96 % to 5.61 %, compared with 1.67 % to 4.42 % in the homogeneous case). Overall, dilution coupled with reaction maximizes nitrate decrease; the homogeneous configuration secures greater gains in the moderate–large class, whereas heterogeneity acts as a brake on the strongest tail and accentuates spatial unevenness.

Figure 10Nitrate reductions with recharge and denitrification. (a–d) Homogeneous; (e–h) heterogeneous.

Figure 11Area-contribution analysis of concentration log-difference response classes under combined MAR and Denitrification. (a) Homogeneous; (b) heterogeneous; (c) relative difference.

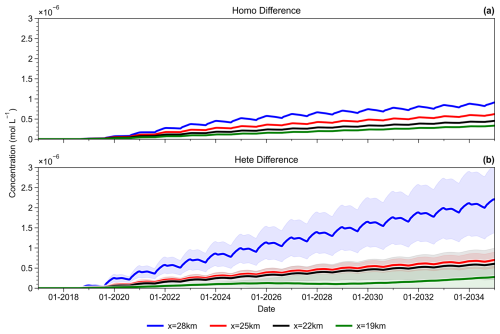

Along the transect at y=13 km, four monitoring points (x=28, 25, 22 and 19 km, listed from nearest to farthest from the recharge reach) were used to evaluate the MAR effect as the concentration difference between the MAR and no-MAR scenarios, where positive values indicate that MAR lowers nitrate and larger values denote stronger reductions. In the homogeneous field (Fig. 12a), all sites exhibit step-like year-to-year increases that align with the August–December recharge period, evidencing a clear multi-year cumulative effect; spatially, the response decays monotonically with distance from the recharge reach (28 km > 25 km > 22 km > 19 km), indicating distance control under near-uniform media. In the heterogeneous field (Fig. 12b), The near-river site (28 km) shows the largest amplitudes, with higher post-season steps and faster cumulative growth than under homogeneity. The two mid-distance sites (x=25 and 22 km) have nearly identical onset times and amplitudes, implying that preferential high-permeability pathways transmit the recharge signal and offset simple distance control. By contrast, the distal site (x=19 km) has a weak mean response but an uncertainty band second only to the near-river site (28 km), indicating large variability in far-field connectivity across realizations. Overall, heterogeneity amplifies the near-field response while flattening differences between the two mid-distance sites, and increases spatiotemporal variance-patterns consistent with the area-class analysis.

Figure 12Time series of MAR and no-MAR concentration difference (ΔC) at monitoring points along y=13 km: (a) homogeneous permeability; (b) heterogeneous permeability.

Average concentration analysis indicates that by 2035, nitrate reductions from recharge alone, denitrification alone, and their combined effect are 2.55 × 10−6, 2.62 × 10−7 and 2.81 × 10−6 mol L−1, respectively, under homogeneous conditions, and 2.75 × 10−6, 2.61 × 10−7 and 3.01 × 10−6 mol L−1 under heterogeneous conditions (Fig. 13a). These correspond to nitrate reductions of 30.72 %, 3.16 %, and 33.8 % in homogeneous, and 31.73 %, 3.01 %, and 34.75 % in heterogeneous settings (Fig. 13b). These findings suggest that: (i) recharge plays a dominant role in nitrate removal, accounting for about 91 % of the total reduction, significantly more than denitrification (about 9 %); (ii) geological heterogeneity slightly enhances the recharge effect (1.01 %), but has little to no impact on denitrification (p>0.05); (iii) the combined effect is nearly equal to the sum of the individual effects (difference < 0.5 %).

This study quantitatively evaluates the impact of MAR on groundwater level recovery and water quality evolution in the groundwater depression area of Xiong'an New Area by using a three-dimensional groundwater flow and solute transport model. The study found that MAR significantly alleviated the groundwater depletion issue, particularly near rivers, where water levels rose rapidly; while the improvements in the central depression area are more modest due to its distance from the recharge area. The reduction in nitrate concentration is mainly attributed to the dilution effect of recharge water, while denitrification had a minimal contribution. Geological heterogeneity significantly influenced the spatial distribution of nitrate distribution, with high-permeability pathways accelerating dilution but exerting little influence on denitrification.

These findings align with previous studies (Li et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020), which emphasize the importance of artificial recharge in groundwater recovery. Our study advances this understanding by integrating nitrate biogeochemical reactions with regional-scale flow dynamics, quantitatively distinguishing the contributions of dilution and denitrification that were often simplified in earlier modeling efforts (Guo et al., 2023a). Moreover, long-term simulations highlight both the potential and the limits of MAR for sustainable groundwater management, showing that while MAR is effective for alleviating depletion and reducing nitrate concentrations, its benefits diminish with distance and are constrained by persistent agricultural inputs. The pronounced rise in water levels near rivers, contrasted with limited recovery in cone centers, highlights the critical role of hydraulic connectivity and suggests that strategically distributed recharge interventions may be more effective. However, the limited availability of organic electron donors and the generally oxidizing shallow aquifers, which constrain microbial nitrate reduction, resulted in minor contributions from denitrification. These field observations justify the exclusion of complex multi-step reaction networks in our model, as the scarcity of primary electron donors constitutes the rate-limiting step rather than intermediate transformation pathways. Although heterogeneity enhances recharge effectiveness by promoting preferential flow, it does not necessarily favor redox reactions, since rapid flow reduces residence times and limits opportunities for denitrification. This aligns with previous studies (Zheng and Gorelick, 2003; Green et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2024), which indicate that while high-preferential flow enhances physical dilution via dispersion, it simultaneously restricts denitrification by shortening groundwater residence times. Consequently, rapid transport results in insufficient effective contact time for substantial biodegradation to occur.

Despite these insights, certain limitations remain. Biogeochemical reactions were simplified to two-step denitrification, omitting other potentially important processes such as assimilation into microbial biomass, transformation into ammonia, which are strongly controlled by oxygen availability, organic carbon, and microbial communities (Mosley et al., 2022; Wang and Li, 2024). Moreover, the current model assumes a constant microbial capacity (μmax), neglecting potential biomass growth or washout during long-term recharge. It may overlook local biogeochemical dynamics, such as biofilm development near infiltration zones, which warrants detailed investigation in future fine-scale studies. The recharge scheme assumed constant conditions, whereas in practice recharge efficiency and timing are likely to vary under different management or climatic scenarios (Kourakos et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2024). The simulated nitrate reduction represents a baseline scenario under constant recharge. In practice, operational intermittency (wetting-drying cycles) could enhance oxygen intrusion into the vadose zone, strengthening denitrification inhibition. Additionally, fluctuations in source water chemistry, particularly reductions in Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) load, would limit electron donor availability. Consequently, actual nitrate mitigation efficiency may be lower than simulated if hydraulic saturation and sufficient carbon supply are not maintained. Furthermore, the complex vertical interactions between groundwater and recharge water were also simplified, especially the dynamic changes of organic matter and nitrogen in deep groundwater, which could also impact nitrate spatial distributions (Levintal et al., 2023; Seibert et al., 2016). The geological heterogeneity was characterized based on a sparse borehole dataset, inevitably introducing structural uncertainty in the delineation of localized contaminant migration, although its impact is partially mitigated through stochastic ensemble simulations.

Future research should strengthen long-term field monitoring of both groundwater levels and solute concentrations to refine model calibration and validation. Expanding the representation of nitrogen transformation pathways and organic matter cycling will enable more realistic predictions of groundwater quality. Additionally, MAR optimization strategies should be evaluated under different hydrological and geological conditions to enhance the effectiveness of water quality and water level recovery. Furthermore, integrating socio-economic factors into MAR will be essential for developing more actionable MAR implementation plans, ensuring their sustainability and wide applicability.

A coupled groundwater flow and solute transport model was used to assess MAR effects in the Xiong'an depression cone, focusing on water-level recovery and nitrate dynamics. Simulations show that MAR markedly alleviates groundwater depletion near rivers, with diminishing effects toward the depression center. Nitrate reductions are primarily driven by dilution from recharge water, while denitrification provides a secondary contribution. Geological heterogeneity shapes the spatial variability of nitrate decreases by channeling flow through preferential pathways, which enhance dilution but do not substantially alter reaction processes.

Overall, MAR proves to be a robust tool for hydraulic recovery; however, its effectiveness for nitrate mitigation is primarily driven by physical dilution. Therefore, its implementation as a remediation strategy requires careful consideration of source water chemistry and continuous injection regimes to maximize benefits. The findings highlight both the potential and the constraints of MAR as a long-term strategy, offering valuable guidance for designing regionally adapted recharge operations.

Data used in this article are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-30-693-2026-supplement.

YZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ZG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review and editing. SW: Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing. KC: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. YW: Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing. ZZ: Supervision, Resources, Writing – review and editing. HS: Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing. JY: Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing. CZ: Writing – review and editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This study was supported by the Center for Computational Science and Engineering of Southern University of Science and Technology.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 42377045), the Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2024B1515020038), and the Innovative Research Team of High-level Local University in Shanghai (grant no. G03050K001).

This paper was edited by Heng Dai and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Appelo, C. A. J. and Postma, D.: Geochemistry, groundwater and pollution, 2nd Edn., Balkema, Rotterdam, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781439833544, 2005.

Bagheri-Gavkosh, M., Hosseini, S. M., Ataie-Ashtiani, B., Sohani, Y., Ebrahimian, H., Morovat, F., and Ashrafi, S.: Land subsidence: A global challenge, Science of The Total Environment, 778, 146193, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146193, 2021.

Carle, S. F. and Fogg, G. E.: Modeling spatial variability with one and multidimensional continuous-lag Markov chains, Mathematical Geology, 29, 891–918, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022303706942, 1997.

Chen, K., Roden, E. E., and Zheng, C.: Hydrological Controls on Riverbed Methane Emissions: A Numerical Investigation of Hydrodynamic and Ebullitive Mechanisms from Site to Basin Scales, Environmental Science and Technology, 59, 15170–15180, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.5c03453, 2025.

Chen, K., Guo, Z., Zhan, Y., Roden, E. E., and Zheng, C.: Heterogeneity in permeability and particulate organic carbon content controls the redox condition of riverbed sediments at different timescales, Geophysical Research Letters, 51, e2023GL107761, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL107761, 2024.

Chen, K., Chen, X., Stegen, J. C., Villa, J. A., Bohrer, G., Song, X., Chang, K.-Y., Kaufman, M., Liang, X., and Guo, Z.: Vertical hydrologic exchange flows control methane emissions from riverbed sediments, Environmental Science and Technology, 57, 4014–4026, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.2c07676, 2023a.

Chen, K., Yang, S., Roden, E. E., Chen, X., Chang, K. Y., Guo, Z., Liang, X., Ma, E., Fan, L., and Zheng, C.: Influence of vertical hydrologic exchange flow, channel flow, and biogeochemical kinetics on CH4 emissions from rivers, Water Resources Research, 59, e2023WR035341, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023WR035341, 2023b.

Chen, Y.: Simulation and prediction of ammonia-nitrite-nitrates content in shallow groundwater in Xiong'an New Area, Master thesis, Hebei GEO University, Shijiazhuang, China, https://doi.org/10.27109/d.cnki.ghbnu.2022.000082, 2022.

Escriva-Bou, A., Hui, R., Maples, S., Medellín-Azuara, J., Harter, T., and Lund, J.: Planning for groundwater sustainability accounting for uncertainty and costs: An application to California's Central Valley, Journal of Environmental Management, 264, 110426, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110426, 2020.

Gong, H., Pan, Y., Zheng, L., Li, X., Zhu, L., Zhang, C., Huang, Z., Li, Z., Wang, H., and Zhou, C.: Long-term groundwater storage changes and land subsidence development in the North China Plain (1971–2015), Hydrogeology Journal, 26, 1417–1427, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-018-1768-4, 2018.

Green, C. T., Böhlke, J. K., Bekins, B. A., and Phillips, S. P.: Mixing effects on apparent reaction rates and isotope fractionation during denitrification in a heterogeneous aquifer, Water Resources Research, 46, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009WR008903, 2010.

Guo, H., Zhang, Z., Cheng, G., Li, W., Li, T., and Jiao, J. J.: Groundwater-derived land subsidence in the North China Plain, Environmental Earth Sciences, 74, 1415–1427, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-4131-2, 2015.

Guo, Z., Chen, K., Yi, S., and Zheng, C.: Response of groundwater quality to river-aquifer interactions during managed aquifer recharge: A reactive transport modeling analysis, Journal of Hydrology, 616, 128847, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128847, 2023a.

Guo, Z., Fogg, G. E., Chen, K., Pauloo, R., and Zheng, C.: Sustainability of regional groundwater quality in response to managed aquifer recharge, Water Resources Research, 59, e2021WR031459, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR031459, 2023b.

Hammond, G. E., Lichtner, P. C., and Mills, R.: Evaluating the performance of parallel subsurface simulators: An illustrative example with PFLOTRAN, Water Resources Research, 50, 208–228, https://doi.org/10.1002/2012WR013483, 2014.

Jasechko, S., Seybold, H., Perrone, D., Fan, Y., Shamsudduha, M., Taylor, R. G., Fallatah, O., and Kirchner, J. W.: Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally, Nature, 625, 715–721, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06879-8, 2024.

Jin, Z., Tang, S., Yuan, L., Xu, Z., Chen, D., Liu, Z., Meng, X., Shen, Z., and Chen, L.: Areal artificial recharge has changed the interactions between surface water and groundwater, Journal of Hydrology, 637, 131318, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131318, 2024.

Karlović, I., Posavec, K., Larva, O., and Marković, T.: Numerical groundwater flow and nitrate transport assessment in alluvial aquifer of Varaždin region, NW Croatia, Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 41, 101084, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2022.101084, 2022.

Kourakos, G., Dahlke, H. E., and Harter, T.: Increasing groundwater availability and seasonal base flow through agricultural managed aquifer recharge in an irrigated basin, Water Resources Research, 55, 7464–7492, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR024019, 2019.

Kuang, X., Liu, J., Scanlon, B. R., Jiao, J. J., Jasechko, S., Lancia, M., Biskaborn, B. K., Wada, Y., Li, H., Zeng, Z., Guo, Z., Yao, Y., Gleeson, T., Nicot, J.–P., Luo, X., Zou, Y., and Zheng, C.: The changing nature of groundwater in the global water cycle, Science, 383, eadf0630, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adf0630, 2024.

Le Traon, C., Aquino, T., Bouchez, C., Maher, K., and Le Borgne, T.: Effective kinetics driven by dynamic concentration gradients under coupled transport and reaction, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 306, 189–209, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2021.04.033, 2021.

Levintal, E., Huang, L., García, C. P., Coyotl, A., Fidelibus, M. W., Horwath, W. R., Rodrigues, J. L. M., and Dahlke, H. E.: Nitrogen fate during agricultural managed aquifer recharge: Linking plant response, hydrologic, and geochemical processes, Science of the Total Environment, 864, 161206, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.161206, 2023.

Levy, Z. F., Jurgens, B. C., Burow, K. R., Voss, S. A., Faulkner, K. E., Arroyo-Lopez, J. A., and Fram, M. S.: Critical aquifer overdraft accelerates degradation of groundwater quality in California's Central Valley during drought, Geophysical Research Letters, 48, e2021GL094398, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL094398, 2021.

Li, C., Li, B., and Bi, E.: Characteristics of hydrochemistry and nitrogen behavior under long-term managed aquifer recharge with reclaimed water: A case study in north China, Science of The Total Environment, 668, 1030–1037, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.375, 2019.

Li, N., Lyu, H., Xu, G., Chi, G., and Su, X.: Hydrogeochemical changes during artificial groundwater well recharge, Science of The Total Environment, 900, 165778, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165778, 2023.

Liang, Y., Ma, R., Prommer, H., Fu, Q. L., Jiang, X., Gan, Y., and Wang, Y.: Unravelling Coupled Hydrological and Geochemical Controls on Long-Term Nitrogen Enrichment in a Large River Basin, Environmental Science and Technology, 58, 21315–21326, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c05015, 2024.

Liu, S., Zhou, Y., Eiman, F., McClain, M. E., and Wang, X.-S.: Towards sustainable groundwater development with effective measures under future climate change in Beijing Plain, China, Journal of Hydrology, 633, 130951, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.130951, 2024.

Ma, R., Chen, K., Andrews, C. B., Loheide, S. P., Sawyer, A. H., Jiang, X., Briggs, M. A., Cook, P. G., Gorelick, S. M., Prommer, H., Scanlon, B. R., Guo, Z., and Zheng, C.: Methods for quantifying interactions between groundwater and surface water, Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 49, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-111522-104534 2024.

Mekala, C. and Nambi, I. M.: Experimental and simulation studies on nitrogen dynamics in unsaturated and saturated soil using HYDRUS-2D, Procedia Technology, 25, 122–129, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2016.08.089, 2016.

Mosley, O. E., Gios, E., Close, M., Weaver, L., Daughney, C., and Handley, K. M.: Nitrogen cycling and microbial cooperation in the terrestrial subsurface, The ISME Journal, 16, 2561–2573, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-022-01300-0, 2022.

Mukherjee, A., Scanlon, B. R., Aureli, A., Langan, S., Guo, H., and McKenzie, A.: Global groundwater: from scarcity to security through sustainability and solutions, in: Global Groundwater, 3–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818172-0.00001-3, 2021.

Pauloo, R. A., Fogg, G. E., Guo, Z., and Harter, T.: Anthropogenic basin closure and groundwater salinization (ABCSAL), Journal of Hydrology, 593, 125787, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125787, 2021.

Peters, C. N., Kimsal, C., Frederiks, R. S., Paldor, A., McQuiggan, R., and Michael, H. A.: Groundwater pumping causes salinization of coastal streams due to baseflow depletion: Analytical framework and application to Savannah River, GA, Journal of Hydrology, 604, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.127238, 2022.

Schafer, D., Donn, M., Atteia, O., Sun, J., MacRae, C., Raven, M., Pejcic, B., and Prommer, H.: Fluoride and phosphate release from carbonate-rich fluorapatite during managed aquifer recharge, Journal of Hydrology, 562, 809–820, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.05.043, 2018.

Schäfer Rodrigues Silva, A., Guthke, A., Höge, M., Cirpka, O. A., and Nowak, W.: Strategies for simplifying reactive transport models: A Bayesian model comparison, Water Resources Research, 56, e2020WR028100, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR028100, 2020.

Seibert, S., Atteia, O., Ursula Salmon, S., Siade, A., Douglas, G., and Prommer, H.: Identification and quantification of redox and pH buffering processes in a heterogeneous, low carbonate aquifer during managed aquifer recharge, Water Resources Research, 52, 4003–4025, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015WR017802, 2016.

Sprenger, C., Hartog, N., Hernández, M., Vilanova, E., Grützmacher, G., Scheibler, F., and Hannappel, S.: Inventory of managed aquifer recharge sites in Europe: historical development, current situation and perspectives, Hydrogeology Journal, 25, 1909–1922, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-017-1554-8, 2017.

Su, G., Wu, Y., Zhan, W., Zheng, Z., Chang, L., and Wang, J.: Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of land subsidence caused by groundwater depletion in the North China plain during the past six decades, Journal of hydrology, 600, 126678, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126678, 2021.

Vergara-Saez, C., Prommer, H., Siade, A. J., Sun, J., and Higginson, S.: Process-Based and Probabilistic Quantification of Co and Ni Mobilization Risks Induced by Managed Aquifer Recharge, Environmental Science and Technology, 58, 7567–7576, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.3c10583, 2024.

Wang, L. and Li, M.: Review of soil dissolved organic nitrogen cycling: Implication for groundwater nitrogen contamination, Journal of Hazardous Materials, 461, 132713, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132713, 2024.

Wu, R., Guo, Z., Zhan, Y., Cao, G., Chen, K., Chang, Z., Li, H., He, X., and Zheng, C.: Impacts of land surface nitrogen input on groundwater quality in the North China Plain, ACS ES&T Water, 4, 2369–2381, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.3c00712, 2024.

Xu, G.: Migration, transformation and simulation prediction of nitrogen, iron and manganese during artificial recharge of groundwater in Rongcheng funnel area of Xiong'an New Area, Jilin University, https://doi.org/10.27162/d.cnki.gjlin.2022.007542, 2022.

Zhan, Y., Murugesan, B., Guo, Z., Li, H., Chen, K., Babovic, V., and Zheng, C.: Managed aquifer recharge in island aquifer under thermal influences on the fresh-saline water interface, Journal of Hydrology, 638, 131496, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.131496, 2024.

Zhan, Y., Guo, Z., Podgorski, J., Zeng, Z., Xu, P., Peng, L., Chen, K., Wu, R., Ding, C., and Andrews, C.: Changes in meat consumption can improve groundwater quality, Nature Food, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-025-01188-x, 2025.

Zhang, H., Xu, Y., and Kanyerere, T.: A review of the managed aquifer recharge: Historical development, current situation and perspectives, Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 118-119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2020.102887, 2020.

Zhang, Y., Wu, H. A., Kang, Y., and Zhu, C.: Ground subsidence in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region from 1992 to 2014 revealed by multiple SAR stacks, Remote Sensing, 8, 675, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8080675, 2016.

Zhao, Q., Zhang, B., Yao, Y., Wu, W., Meng, G., and Chen, Q.: Geodetic and hydrological measurements reveal the recent acceleration of groundwater depletion in North China Plain, Journal of Hydrology, 575, 1065–1072, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.06.016, 2019.

Zheng, C. and Gorelick, S. M.: Analysis of solute transport in flow fields influenced by preferential flowpaths at the decimeter scale, Groundwater, 41, 142–155, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.2003.tb02578.x, 2003.

Zheng, C. and Guo, Z.: Plans to protect China's depleted groundwater, Science, 375, 827–827, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn8377, 2022.

Long-term overuse of groundwater has lowered water levels and increased pollution in parts of northern China. We studied whether adding river water back into the ground can restore groundwater and reduce nitrate pollution. Using computer simulations based on field data, we found that recharge can significantly raise water levels and lower nitrate levels, mainly by dilution rather than natural removal processes.

Long-term overuse of groundwater has lowered water levels and increased pollution in parts of...