the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Streamflow generation in a nested system of intermittent and perennial tropical streams under changing land use

Giovanny M. Mosquera

Daniela Rosero-López

José Daza

Daniel Escobar-Camacho

Annika Künne

Patricio Crespo

Sven Kralisch

Jordan Karubian

Andrea C. Encalada

Despite the increased interest in the hydrology of intermittent hydrological streams in recent years, little attention has been given to these systems in tropical forest environments. We present a unique set of hydrometric, stable isotopic, geochemical, and landscape mapping information to obtain a mechanistic understanding of streamflow generation in 20 nested catchments (< 1–159 km2) draining intermittent and perennial streams and rivers in the Chocó-Darien ecoregion, a tropical biodiversity hotspot, located in the Pacific lowlands of northern Ecuador that has been strongly degraded by deforestation and agricultural encroachment during the last half-century. Hydrological intermittency is mainly controlled by antecedent wetness due to the strong seasonality of precipitation. Nevertheless, the streambed of catchments draining intermittent streams remains humid throughout the year, even when surface water stops flowing, since evapotranspiration is reduced due to continued cloudy and foggy conditions during the dry season. Intermittent streams mainly located in conserved forested headwaters with shallow soils and a low permeability bedrock have a faster streamflow response to rainfall and shorter recession times than the perennial streams with high permeability bedrock in the catchment's degraded middle and lower parts. Isotopic information shows that rainfall during the wet period (January to May) contributes to streamflow generation in the intermittent streams, whereas rainfall during the wet season recharges the subsurface water storage of the perennial streams. Concentrations of major ions and electrical conductivity were lower in intermittent streams compared to perennial streams. We found a strong correlation between the catchments' geology and geochemical signals and a weak correlation with the topography, land cover, and soil type. These findings indicate that shallow subsurface flow paths through the organic horizon of the soil dominate streamflow generation in intermittent streams due to the limited water storage capacity of their bedrock with very low permeability. On the contrary, high bedrock permeability increases the water storage capacity and is replenished during the wet period, helping sustain streamflow generation throughout the year for the perennial streams. These findings suggest that geology may play an important role in driving hydrological intermittency, even in highly degraded tropical forest catchments, and provide key process-based information useful for water management and hydrological modelling of intermittent hydrological systems.

- Article

(5069 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(492 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Intermittent hydrological systems are defined as drainage areas that partially or totally cease to flow during part of the year (Shanafield et al., 2021; van Meerveld et al., 2020). Those systems account for more than half the length of the global drainage network and this proportion is expected to increase due to changes in land use and global climate (Messager et al., 2021). The dynamic of intermittent hydrological systems generally varies markedly between high flows during wet periods and no flow during dry ones, resulting in important socioeconomic, ecological, and biological implications (Costigan et al., 2017). As a result, flow from intermittent hydrological systems influences water quality and provides key ecosystem services, including water provision to humans and the preservation of aquatic and terrestrial life that depends on these (Pastor et al., 2022). As such hydrological dynamics can be caused by one or a combination of several factors, including hydrometeorological conditions, surface and subsurface characteristics (i.e. topography, soils, geology), and land cover (e.g. groundwater extraction, deforestation; Costigan et al., 2016); obtaining a mechanistic (process-based) understanding of streamflow generation in intermittent hydrological systems is paramount to improving their conservation and sustainable management (Leigh et al., 2016; Vander Vorste et al., 2020) and to develop accurate predictive models of hydrological intermittency to assess the impacts of global change drivers (Dohman et al., 2021; Shanafield et al., 2021). This knowledge is particularly needed in tropical regions that host the largest proportion of the planet's biodiversity (Myers et al., 2000) and are drastically affected by changes in land use due to fast population growth (Newbold et al., 2020).

Despite the social-ecological importance of intermittent hydrological systems composed of a combination of intermittent and perennial streams (van Meerveld et al., 2020), field-based studies that allow obtaining a sound mechanistic understanding of streamflow generation in these systems remain limited worldwide (Shanafield et al., 2021). Indeed, only a few studies have investigated the sources and flow paths of water influencing streamflow generation in intermittent rivers and streams. For instance, streamflow generation in an intermittent low relief and highly weathered catchment with a subtropical climate in North Carolina, USA was investigated by Zimmer and McGlynn (2017), who found that two different water flow paths influencing hydrograph recession were activated depending on seasonal evapotranspiration. In semi-arid southeast Australia, Zhou and Cartwright (2021) quantified the sources of baseflow in an intermittent catchment. They determined that near-river water storage was the main source of baseflow as opposed to regional groundwater. In South Africa, Banda et al. (2023) assessed the interaction of surface water and groundwater in an intermittent catchment with Mediterranean climate. They found that geology plays a key role in surface-groundwater hydrological connectivity. Bourke et al. (2021) also reported that bedrock permeability controls streamflow generation in a low-relief and semi-arid region in northwestern Australia.

The flow paths influencing surface flow in an intermittent stream section in a semi-arid climate in the Rocky Mountains, Idaho, USA were evaluated by Dohman et al. (2021), who concluded that flow cessation occurred where hillslopes did not laterally contribute to streamflow and at sites with greater vertical losses from the stream bed to groundwater. Streamflow generation in a tropical dry forest catchment near the Pacific coast of central Mexico was investigated by Farrick and Branfireun (2015). They reported that vertical water flow paths and the contribution of water stored in the saturated zone of the catchment were the most influential factors driving streamflow generation. Through hydrological modelling, Gutierrez-Jurado et al. (2021) pinpointed that soil type and hydraulic properties can exert great control on the mechanisms driving flow generation in a Mediterranean coastal catchment in South Australia by influencing unsaturated subsurface water storage. Regarding changes in land use, in a strongly seasonal Mediterranean region in the Central Spanish Pyrenees deforestation caused a change in streamflow hydrological dynamics due the loss of forest cover, including higher peak flows and higher low flows, compared to a conserved forested catchment (Serrano-Muela et al., 2008). Although these investigations have helped to better comprehend streamflow generation in intermittent hydrological systems, this understanding remains elusive in highly seasonal tropical forest environments. This lack of understanding not only limits water management in intermittent hydrological systems, but also the assessment of how their hydrological dynamic compares to those in non-tropical environments.

One of the key factors limiting the advancement in the understanding of streamflow generation in intermittent hydrological systems is the difficulty of collecting data for robust conceptualization of flow processes (e.g. Jacobs et al., 2018; Mosquera et al., 2016a; Timbe et al., 2017). While hydrometric (e.g. water level or discharge) data alone allow characterizing the dynamics of streamflow and its characteristics (Willems, 2014; Zimmer and McGlynn, 2017), such data does not provide information about the sources and main flow paths of water contributing to streamflow (Leibundgut et al., 2009; McDonnell and Kendall, 1992; Mosquera et al., 2016a). Isotopic (e.g. water stable isotopes) and geochemical (e.g. dissolved elements) tracers as well as water physicochemical parameters (e.g. water temperature and electrical conductivity) have been used to identify water sources (e.g. Barthold et al., 2010; Correa et al., 2017; Inamdar et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2004; Penna et al., 2014) and infer the main flow paths water follows through catchments as rainfall becomes streamflow (e.g. Asano et al., 2002; Lahuatte et al., 2022; Laudon et al., 2004; Mosquera et al., 2020; Muñoz-Villers and McDonnell, 2012; Ramón et al., 2021; Tetzlaff et al., 2015). In addition, mapping of biophysical landscape characteristics using nested monitoring systems (as opposed to single or paired catchment approaches) has proven useful to understanding the influence of catchment characteristics such as topography, soils, geology, and land cover on streamflow generation (e.g. McGuire et al., 2005; Mosquera et al., 2015, 2016b; Muñoz-Villers et al., 2016; Staudinger et al., 2017). The clear benefits of employing multimethod approaches that combine hydrometric, isotopic, geochemical, and landscape mapping, in humid, perennial environments, suggest their great potential to achieve a sound process-based understanding of intermittent hydrological systems (e.g. Banda et al., 2023; Bourke et al., 2021; Farrick and Branfireun, 2015). Thus, the use of such approaches to investigate streamflow generation in those systems should be encouraged, particularly in regions where hydrological information is scarce but urgently needed for timely management of water resources and aquatic ecosystems, including understudied tropical areas.

Considering the lack of studies on streamflow generation in intermittent hydrological systems in tropical regions, particularly in South America (Shanafield et al., 2021), we aim to fill this knowledge gap. To this end, we use a multimethod approach to obtain a unique data set including hydrometric, isotopic, geochemical, and landscape mapping information collected through a nested monitoring system comprising 20 intermittent and perennial streams within the Cube River catchment located in the Ecuadorian Pacific lowlands of the Chocó-Darien ecoregion. The studied catchment has undergone intense deforestation and agricultural activities in the last 50 years and is representative of regional land use change (MAATE, 2022). Therefore, the monitoring setup in this land use template allows us to pose a regional overarching question: what are the main factors influencing streamflow generation in a nested system of intermittent and perennial tropical streams under changing land use? Our working hypotheses are as follows: (i) if land use has the largest effect on streamflow generation, overland flow would increase in highly deforested catchments thus leading to diminished subsurface recharge and less perennial flow; whereas (ii) if geology is the dominant factor, the catchments with high subsurface water storage would generate flow perennially and intermittent flow would occur in catchments with low subsurface water storage. On the one hand, assessing these hypotheses will add to the overall mechanistic understanding of the hydrology of intermittent rivers and streams to develop robust models of hydrological intermittent regimes at different spatial and temporal scales. On the other hand, this knowledge will also provide key information to assess water resources availability, manage and conserve aquatic ecosystems, and evaluate the resilience of the system to global change stressors.

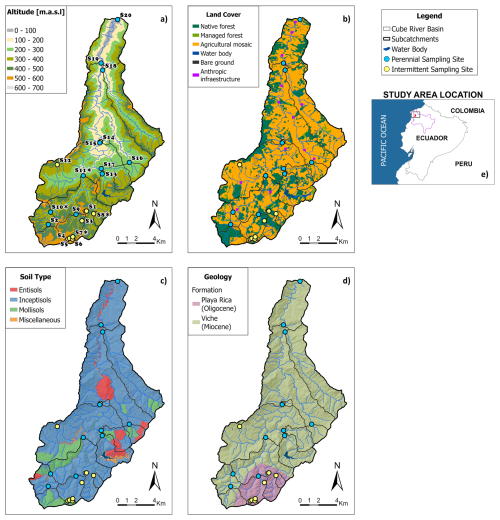

The study was conducted at the Cube River catchment (Fig. 1). The catchment is a tributary of the Esmeraldas River Basin that drains into the Pacific Ocean. It is located in the Pacific lowlands of northern Ecuador (0.37° N, 79.66° W) within the Chocó-Darien ecoregion (Dinerstein et al., 2017), a worldwide biodiversity hotspot extending from southern Panama to northern Ecuador (Myers et al., 2000). The geological and climatological configuration of the ecoregion provides a variety of ecosystems distributed between coastal ridges and the Andean cordillera that modulates regional and local climate patterns favouring exuberant vegetative formations, high species endemism, and ecosystem services (Fagua and Ramsey, 2019). Part of the Cube River catchment situates within a protected area that is surrounded by two mountain ranges: the Mache and the Chindul ridges (200–800 m a.s.l.), a coastal massif approximately 100 km west of the Andes (hereafter referred to as the Mache-Chindul Mountain range). The catchment drains from south to north, encompassing a drainage area of 159 km2, with a mean slope of 32 %, and a mean altitude of 339 m a.s.l. ranging from 53 and 688 m a.s.l. (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1Cube River catchment (159 km2) maps of: (a) altitude, (b) land cover, (c) soil type, and (d) geology. (e) Location of the Cube River catchment (red area) in the lower part of the Esmeraldas River basin (purple line) in northwestern Ecuador. Maps (a) to (d) show the Cube River catchment drainage network and the intermittent (yellow circles) and perennial (blue circles) sampling sites at the outlet of 19 nested subcatchments (S1 to S19) and the outlet of the catchment (S20) where hydrologic, geochemical, and isotopic data were collected during six monitoring campaigns during the period January–December 2021. The * symbol next to the name of the sampling sites in (a) denotes sites where water level data were continuously monitored during the study period.

Mean annual precipitation at a gauging station of the Ecuadorian National Agency of Hydrology and Meteorology (INAMHI) located approximately 20 km from the study area at 100 m a.s.l. during the period 2005–2017 is 1256 mm yr−1. Seventy-five percent of precipitation is concentrated in the wet period extending from January to May and 25 % is distributed during the dry period from June to December. This seasonal hydrometeorological condition results in the occurrence of hydrological intermittence, particularly in headwater tributaries.

The catchment reflects regional land-cover change, where lush tropical forests of the Chocó-Darien ecoregion have been extensively degraded over the past half-century by deforestation, cultivation, and cattle grazing (Cuesta et al., 2017). Today, an agricultural mosaic of grazing and agricultural land covers 69 % of the catchment, with only 28 % of native (e.g. primary and secondary) forest land remaining (Fig. 1b). The upper part of the catchment is situated within private protected reserves for land-forest conservation, including Bilsa, Fundación para la Conservación de los Andes Tropicales (FCAT), and the national protected area of the Mache-Chindul Ecological Reserve.

Soils in the study area are generally shallow regardless of the type. According to the USDA Soil Taxonomy (Soil Survey Staff, 2022), the soils are classified as inceptisols, mollisols, entisols, and miscellaneous (Fig. 1c; MAG, 2019). Inceptisols distributed along the whole catchment are the dominant soils covering 79 % of the study area (Fig. 1c). These soils possess a slightly acid-to-neutral pH and have a clay-to-clay loam texture. Mollisols cover 11 % of the catchment and are occasionally found in the south and central parts of the catchment. These soils are slightly acidic and clayey. Entisols cover 7 % of the study site and are sporadically found in the central part of the catchment. They present a moderately acid to neutral pH and a clay-to-clay loam texture. Undescribed soils classified as “Miscellaneous” cover less than three percent of the catchment area and are found as small patches in the central part of the catchment.

The underlying bedrock belongs to two geological formations. The Playa Rica formation covers 11 % of the catchment and is primarily found in headwaters areas (Fig. 1d). This formation dates from the Oligocene period (23–33 Ma). It possesses a very low bedrock permeability with a thickness of 800 m (DIIEA, 2010) and its lithology is composed of shales and sandstones. The younger Viche formation, dating from the Miocene (5–23 Ma), has a medium bedrock permeability with a thickness of approximately 400 to 1000 m. It covers 89 % of the study area and is distributed across the remaining of the catchment. The Viche formation lithology mainly comprises silty clay with calcareous lenses, shales, and sandstones (DIIEA, 2010).

3.1 Monitoring scheme and catchment features

We used a nested monitoring system comprised of 20 sampling sites including a mixture of intermittent and perennial streams within the Cube River catchment to collect hydrological, isotopic, and geochemical data from January to December 2021. Since no hydrological studies were previously carried out in the study area, the selection of sampling sites was carried out in collaboration with staff members of the FCAT reserve and the support of researchers from the “Securing biodiversity, functional integrity and ecosystem services in DRYing riVER networks” (DRYvER) project (Datry et al., 2021). The reserve staff included local community members who have ample knowledge of the area and have been actively participating in ecological and biological projects in the area for over 15 years. Such knowledge was invaluable in identifying appropriate sampling sites based on accessibility, security, and hydrological (intermittent vs. perennial) conditions. The sites included 19 subcatchments (S1 to S19 in Fig. 1a) and the outlet of the catchment (S20). Eleven sites were classified as perennial and 9 as intermittent according to their drying patterns (Fig. 1). The sampling sites were spatially distributed across the catchment from the headwaters, which tend to be intermittent to the middle and lower parts where flow is perennial (Fig. 1a–d).

As part of the study, we developed thematic maps of the catchment biophysical characteristics (Fig. 1a–d). The altitude map was constructed using the Alos Palsar Digital Elevation Model (30 m resolution) from the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency. Due to the constant presence of clouds or fog across the catchment, we did not find a single satellite image showing the land cover of the whole study area. Thus, the land cover map was built using SENTINEL and PLANET satellite imagery (USGS, 2023) collected during the period 2019 to 2022. It is worth noting that due to the resolution of the satellite images and the similarity of the cultivation and cattle grazing spectra, we could not readily distinguish between these land cover types, so they were aggregated and classified into a single category hereafter referred to as agricultural mosaic. Similarly, we could not distinguish between native primary and secondary forests, so both types of forests were aggregated into a single category of native forests. Soil and geological maps were built using information from the Ecuadorian Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAG, 2019). The main topographic, soil, geologic, and land cover characteristics of the 20 sampling sites are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1Main landscape characteristics of the 20 sampling sites within the Cube River catchment. Sites marked with an asterisk (*) represent intermittent streams.

a NF: native forest. MF: managed forest. AM: agricultural mosaic (includes crops and pasture for cattle grazing). WB: water body. BG: bare ground.

b MOL: Mollisols. ENT: Entisols. INC: Inceptisols. MIS: Miscellaneous.

c PR: Playa Rica Formation. VI: Viche Formation.

3.2 Hydrological data collection and analysis

Water level (or stage) was continuously recorded using HOBO® U20L pressure transducer water level loggers (USA; accuracy 4 mm) every 15 min at four sampling sites during the study period (January–December 2021) to identify the hydrological dynamics. The sites were selected based on their hydrological regime. That is, the loggers were placed in two subcatchments with intermittent hydrological conditions (S7 and S8 in Fig. 1a) and in two subcatchments with perennial flow (S10 and S11). Water level hydrographs were normalized to a maximum value of 1 by dividing the observed water level data by the maximum water level recorded during the study period to ease visualization. Normalized water level data were used to characterize the temporal variability of the region's hydrological regime (e.g. Jachens et al., 2020; Kirchner et al., 2020) and identify differences in flow dynamics between intermittent and perennial streams using the Water Engineering Time Series PROcessing tool (WETSPRO; Willems, 2014). WETSPRO was used to separate the hydrographs into baseflow, shallow subsurface flow (or interflow), and overland flow components and to identify independent hydrological events (e.g. Correa et al., 2016; Lazo et al., 2019). The baseflow, shallow subsurface, and overland flow contributions to total streamflow; the recession time of baseflow and shallow subsurface flow; and the time to peak and time from peak to baseflow indices of event hydrographs were used to compare flow dynamics between intermittent and perennials streams (Dingman, 2015). To identify potential differences in hydrological dynamic during the wet and dry periods, we analysed the hydrological response during events that presented a simultaneous water level response for both stream types during each period.

3.3 Isotopic data collection and analysis

The isotopic composition of streamflow at the 20 sampling sites (S1–S20; Fig. 1a) was monitored to identify potential differences in the hydrological behaviour of intermittent and perennial sites. Samples for isotopic analysis were collected during six monitoring campaigns (M1–M6) between January and December 2021 at each sampling site. The campaigns were conducted roughly every two months, starting in late February 2021 (M1) and finalizing in mid-December 2021 (M6).

Grab samples of stream water were filtered using 0.45 µm polypropylene single-use syringe membrane filters (Puradisc 25 PP Whatman Inc., USA) and stored in 2 mL amber glass vials. The vials were sealed with parafilm and refrigerated at 10 °C to avoid evaporative fractionation. The oxygen-18 and hydrogen-2 isotopic ratios of the water samples were measured using a cavity ringdown spectrometer (Picarro 2130-i) at the Water and Soil Quality Laboratory of the University of Cuenca. Three Picarro secondary standards were used in the analysis: ZERO (δ2H = 0.3 ± 0.2 ‰, δ18O = 1.8 ± 0.9 ‰), MID (δ2H = −20.6 ± 0.2 ‰, δ18O = −159.0 ± 1.3 ‰), and DEPL (δ2H = −29.3 ± 0.2 ‰, δ18O = −235.0 ± 1.8 ‰). The long-term analytical precision of the instrument is 0.5 ‰ for hydrogen-2 (δ2H) and 0.1 ‰ for oxygen (δ18O). Samples were injected six times and the first three were discarded to avoid memory effects (Penna et al., 2012). For the last three injections, we calculated the maximum δ18O and δ2H differences and compared them with the analytical precision of the instrument. The differences for all samples were smaller than the analytical precision. The samples were checked for organic contamination using ChemCorrect™ (Picarro Inc., USA), and no organic contamination was detected. The isotopic composition of the isotopic ratios is reported in per mill values (‰) using the δ notation according to the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (V-SMOW; Craig, 1961). The spatial (across the 20 sampling sites, S1–S20) and temporal (across the six monitoring campaigns, M1–M6) variability of the stable isotopic composition of oxygen-18 (δ18O), hydrogen-2 (δ2H), and deuterium excess (d-excess = δ2H–8 ⋅ δ18O; Dansgaard, 1964) were used to identify differences in the hydrological behaviour of the system (e.g. Lahuatte et al., 2022; Mosquera et al., 2016a). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Wilcoxon, 1945) was used to assess differences between the stream water isotopic composition of intermittent and perennial streams at a 95 % confidence level (i.e. p value < 0.05) given that data were non-parametric.

3.4 Geochemical data collection and analyses

The geochemical composition of stream water was also monitored at the 20 sampling sites during the six monitoring campaigns. The geochemical data were used to identify the potential effect of biophysical landscape features on the water flow paths in intermittent and perennial streams across the Cube River catchment.

Geochemical monitoring included the in-situ measurement of water physicochemical parameters and the collection of stream water samples to determine their solute composition via laboratory analyses. The physicochemical parameters included water temperature, electrical conductivity, dissolved oxygen, and pH. These parameters were measured in-stream at each sampling site during each monitoring campaign using a portable multiparameter probe (YSI, PRO DSS®; USA). The probe was laboratory-calibrated prior to each of the sampling campaigns.

To determine stream water dissolved solute concentrations, two types of samples were collected. Water samples for the analysis of chemical oxygen demand (COD), alkalinity, total N (TN), total P (P), SO, NO, F−, and total organic carbon (TOC) were collected in two unfiltered 500 mL high-density polyethylene (HDPE; Thermo Scientific™ Nalgene™, USA) containers previously rinsed with 10 % HCl. COD was analysed using the 20–1500 mg L−1 COD (HR) Hach kit following the Standard Method (SM) 5220 D (APHA, 2023). Alkalinity was measured according to the Standard Methods (SM) protocol SM 2320 B (APHA, 2012). TN concentrations were determined using the Kjeldahl method (Buchi, speed digester K436, scrubber K415 and KjelFlex K360) following the protocol SM 4500-Norg B (APHA, 2012). P was measured following the colorimetric analysis described in the SM 4500-P B (APHA, 2012). SO, NO, and F− were analysed by the colorimetric methods SM 246 C, SM 4500 NO D and SM 4500 F− C, respectively (APHA, 2012). TOC was determined by combustion catalytic oxidation using a Shimadzu TOC-L analyser, following the EPA 9060a method.

Water samples for analysing 18 dissolved elements, including Al, As, Ba, Ca, Cd, Co, Cu, Cr, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, Mo, Na, Ni, Pb, V, and Zn were collected in two 60 mL HDPE (Thermo Scientific™ Nalgene™, USA) bottles rinsed with 10 % HCl. The latter were filtered using 0.45 µm polypropylene single-use syringe membrane filters (Puradisc 25 PP Whatman Inc., USA) and preserved with 2 % HNO3. These elements were analysed with an ICP-OES (Thermo Scientific iCap 7000), following the Standard Method SM 3120 B.

The Pearson coefficient (r) of all calibration curves was greater than 0.995. The method's detection limits were calculated as three times the standard deviation of the blank (EURACHEM/CITAC, 2012). All the results obtained were the average of three repeated analyses. Quality assurance and quality control analyses were performed every 10 samples applying standard dilutions for metals (ERA 500 Trace Metal certified reference material, Waters™), for TOC (1000 mg L−1, ERA Waters™), and for TN (glycine, Across Organics). The geochemical analyses were conducted at the Core Lab de Ciencias Ambientales at Universidad San Francisco de Quito. Out of the 24 measured solutes, we only report the elements that had concentrations above detection limits (Table S1 in the Supplement) at each sampling site and monitoring campaign to allow for a robust comparison of the spatiotemporal geochemical conditions of stream water across the nested monitoring system. The measured values of the reported solutes represented the average of the two replicates collected at each study site and monitoring campaign.

Relationships between pairs of solutes were examined through Spearman correlation (r) analysis using the median concentration of all samples collected during all monitoring campaigns at each sampling site. Spearman correlations were considered statistically significant when presenting a 95 % level of confidence (p value < 0.05). Statistically significant correlations were considered strong when r > 0.75 and moderate when 0.50 < r ≤ 0.75 (Akoglu, 2018). Correlations were considered weak for r ≤ 0.50, regardless of their statistical significance. The same statistical test was used to identify potential relations between the median solutes' concentrations and biophysical landscape characteristics (i.e. topography, soils, geology, and land cover). Differences in stream water chemistry were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Wilcoxon, 1945) at a 95 % confidence level (i.e. p value < 0.05) since data were non-parametric.

4.1 Landscape characteristics of the nested catchments

Catchments draining intermittent streams had smaller drainage areas (< 1 km2) than catchments draining perennial streams and rivers (> 3 km2; Table 1, Fig. 1a). The mean altitude of the catchments varied between 308 and 600 m a.s.l., with intermittent catchments having mean altitudes above 400 m a.s.l. (except for catchment M14; Table 1). The mean slope of the catchments ranged from 14 % to 45 %. Two headwater catchments had the gentler slopes (S1 and S3) and catchment S12 had the steepest slope. Land cover varied widely across the catchments. Three headwater catchments (S1–S3) had native forest cover higher than 60 %, whereas native forests covered less than 50 % in the rest of the catchments, except for catchments S6 and S10. Except for the catchments dominated by native forest cover, the agricultural mosaic land cover dominated in the rest of the catchments (Table 1, Fig. 1b). The extent of water bodies and bare ground was less than 2 % in most catchments, except in catchment S13 that had a surface water body, the Cube lagoon, covering 10 % of its drainage area and catchment S3 that had a bare ground area of 6 %. Although inceptisols tended to dominate in the lower part of the Cube River catchment, no clear spatial patterns among the nested monitoring system could be identified (Table 1, Fig. 1c). The Playa Rica geological formation dominated in the small headwater catchments (S1–S9; Table 1, Fig. 1d); whereas the Viche formation was mainly found in catchments located in the middle and lower parts of the Cuber River catchment (Fig. 1d).

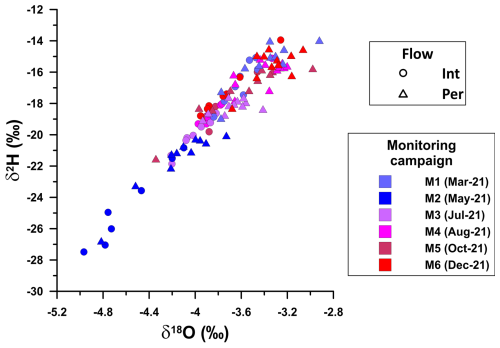

4.2 Hydrological dynamics

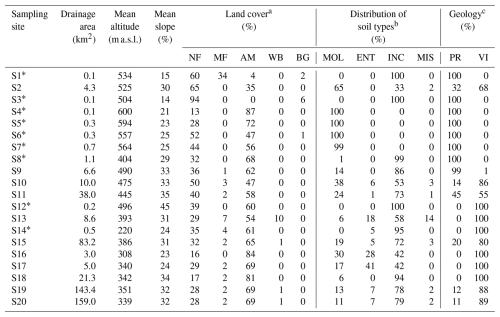

The yearly hydrographs (Figs. 2a–b) depict the strong seasonality of the study area, with a wet period lasting from January to mid-June showing the frequent occurrence of events generating the highest peaks throughout the year. Following the wet period, a transition period from mid-June to mid-July is characterized by the occurrence of events with less frequency that produced lower peak values than in the wet period. A dry period from mid-July to December subsequently occurred, in which the water level was generally the lowest except for a few events observed during late September–early October and late December 2021.

Figure 2Hourly time series of normalized water level hydrographs showing the hydrological behaviour of (a) an intermittent stream (site S7) and (b) a perennial stream (site S11) within the Cube River catchment for the period January–December 2021 and for an event during the wet period (shown in blue in panels c and d) and the dry period (shown in red in panels e and f). Results from the graphical hydrograph analysis are written in the boxes of each subplot: QB = baseflow contribution to total streamflow; QSS = shallow subsurface flow or interflow contribution to total streamflow; QO = overland flow contribution to total streamflow; kB = recession time of baseflow; kSS = recession time of shallow subsurface flow or interflow; tP = time to peak; tP−B = time from peak to baseflow.

At a yearly time scale, the hydrographs show that intermittent streams (Fig. 2a) returned to zero-flow faster after rainfall cessation than perennial streams returned to baseflow (Fig. 2b). The hydrographs also show that perennial streams had longer recessions than the intermittent streams. The graphical separation of the hydrographs into their subcomponents quantitatively depicts clear differences in the hydrological dynamic of both types of flow regimes. Baseflow was lower (0.20) and overland flow (0.15) was higher in intermittent streams (Fig. 2a) than in perennial streams in which baseflow was 0.40 and overland flow was 0.05 (Fig. 2b). In addition, the recession times of baseflow and shallow subsurface flow of intermittent streams (12.5 and 0.4 d, respectively) were shorter than in perennial streams (18.8 and 1.7 d, respectively).

The hydrographs of representative events during the wet period in intermittent and perennial streams are presented in Fig. 2c and 2d, respectively. These event hydrographs show that the time to peak (2 h) and the time from peak to baseflow (60 h) in intermittent streams (Fig. 2c) were shorter than those in perennial streams in which the former was 3 h and the latter > 89 h (Fig. 2d). Even though the time to peak and time from peak to baseflow were longer for events during the dry period (Fig. 2e–f), the difference in the dynamic between them was similar in both periods. That is, during the dry period the time to peak (5 h) and the time from peak to baseflow (87 h) in intermittent streams (Fig. 2e) were also shorter than those in perennial streams (9 and 158 h, respectively; Fig. 2f).

4.3 Isotopic characterization of stream water

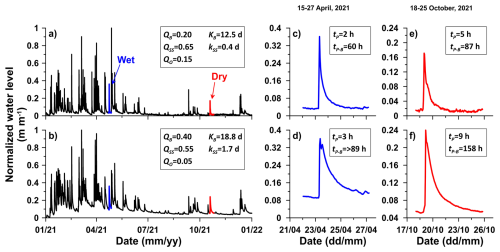

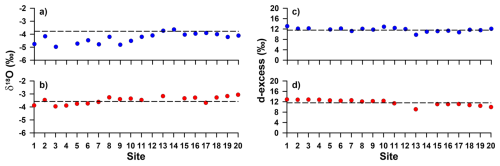

Figure 3 depicts that the isotopic composition of stream water remains relatively stable throughout the year, varying in a narrow isotopic range (−2.9 ‰ to −4.3 ‰ in δ18O and −14.5 ‰ to −21.3 ‰ in δ2H); except for monitoring campaign M2 carried out in late April 2021 during the wettest period of the year (Fig. 2a–b). During the wettest period, most sites showed lower isotopic values (i.e. more depleted in heavy isotopes) than the rest of the year, reaching values as low as −4.9 ‰ in δ18O and −27.6 ‰ in δ2H. From the beginning of the wet season (M1) to the early dry season (M4) the isotopic ratios of the intermittent streams tended to be smaller compared to the perennial streams (Fig. 3); while the isotopic composition in both intermittent and perennial streams varied in a similar range in the middle and late dry season (M5 and M6).

Figure 3Relationship between oxygen-18 (δ18O) and hydrogen-2 (δ2H) isotopic ratios in stream water samples collected at intermittent (circles) and perennial (triangles) sites within the Cube River catchment during six monitoring campaigns (M1–M6) carried out during the wet (M1 and M2), transition (M3), and dry (M4, M5, and M6) periods in 2021. The date of the sampling campaigns (mm-yy) is shown in parentheses in the legend. Monitoring campaigns M2 and M6 correspond to the wettest (dark blue symbols) and driest (red symbols) sampling periods, respectively.

During the wettest period, the isotopic composition of δ18O in the smallest subcatchments (S1–S8) was significantly (p value < 0.05) depleted (mean ± standard deviation: −4.7 ± 0.3 ‰) compared to sampling sites with larger drainage areas (−4.1 ± 0.3 ‰) (Fig. 4a). Conversely, during the dry period there was no systematic difference in δ18O across the sampling sites (−3.5 ± 0.3 ‰), and most sites generally had isotopic values close to the average value (−3.7 ‰) of all samples collected during all monitoring campaigns (Fig. 4b). During the rest of the monitoring campaigns carried out during the beginning of the wet period (M1), the transition period (M3), and the rest of the dry period (M4 and M5), the δ18O across the catchments was similar to that of the driest period shown in Fig. 4b (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). The δ2H varied similarly to those shown for δ18O and thus is not shown for brevity. d-excess was consistently close to the average of all samples collected during all monitoring campaigns (+11.6 %) regardless of the monitoring period (Fig. 4c–d), showing no spatial and temporal differences among sampling sites and monitoring periods.

Figure 4(a, b) Oxygen-18 (δ18O) isotopic ratios and (c, d) d-excess for stream water samples collected at the 20 sampling sites within the Cube River catchment during the wettest (dark blue circles in a and c) and driest (red circles in b and d) monitoring periods (i.e. M2 and M6, respectively). The dashed lines in (a) and (b) represent the average δ18O value (−3.7 ‰) and in (c) and (d) represent the average d-excess value (+11.6 %) of the samples collected at all sampling sites during the six monitoring campaigns carried out in 2021 for reference. In the x axis, the sampling sites are ordered according to the elevation of their outlets, generally corresponding to the sites with the smallest drainage areas at the Cube River headwaters and the sites with the largest drainage areas downstream toward the catchment's outlet (Fig. 1a, Table 1).

4.4 Geochemical characterization of stream water

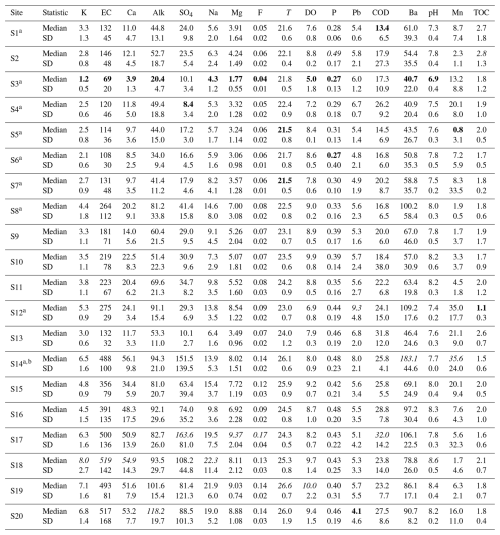

Solutes that cause harmful effects on humans and aquatic ecosystems' health even at small concentrations (WHO Water, Sanitation, Hygiene and Health Team, 2008), such as As, Cd, Co, Cu, Cr, and Ni, were not detected in any of the analysed samples. Other elements with concentrations below detection limits for more than 20 % (n = 4) of the sampling sites for at least one monitoring campaign were not included in the analyses (i.e. TN, NO, Al, Fe, Mo, V, and Zn). Therefore, results for 11 solutes (i.e. SO, F−, P, TOC, Ba, Ca, K, Mg, Mn, Na, and Pb) in addition to alkalinity, COD, and the in-situ measured physicochemical parameters (i.e. temperature, electrical conductivity, dissolved oxygen, and pH) are reported (i.e. 17 geochemical parameters).

Table 2 depicts a wide range of variations in the water geochemical characteristics along the Cube River catchment. Except for P, TOC, and Pb, the lowest values of the geochemical parameters were generally observed in the headwaters of the Cube River catchment (S1–S7). In contrast, the sampling sites with the largest drainage areas (S17–S20) tended to have the highest concentrations. Even though the largest concentrations of P and TOC were observed at a forest headwater catchment generating perennial flow (S2); the lowest concentration for P was found at S3 and S6, and the lowest concentration for TOC was observed at S12 (Table 2). The lowest concentration of Pb was found at S20 and the highest at S12.

Table 2Median and standard deviation (SD) of stream water physical-chemical parameters and solute concentrations of the 20 sampling sites within the Cube River catchment. Sites marked with a represent intermittent streams. All sites were sampled six times in 2021, except for site S14 (marked with b) that completely dried during three sampling campaigns in the dry season. Electrical conductivity (EC) and temperature (T) are reported in µS cm−1 and °C, respectively. Solute concentrations are reported in ppm, except for Ba, Pb, and Mn that are reported in ppb. Values in bold are the highest and values in italics are the lowest of the monitored water chemical parameters. EC: electrical conductivity, Alk: Alkalinity, T: Temperature, DO: dissolved oxygen, COD: chemical oxygen demand, and TOC: total organic carbon.

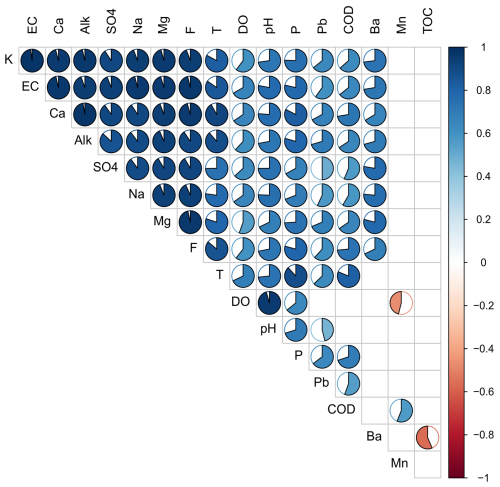

There was a strong positive correlation among several pairs of stream water physical-chemical parameters. These parameters included Ca, electrical conductivity, alkalinity, SO, F−, Na, Mg, and temperature (Fig. 5). The aforementioned parameters and DO, pH, P, Pb, COD, and Ba were moderately, positively, and significantly correlated. Mn showed a moderate and positive correlation with COD, and a weak and negative correlation with DO. TOC only showed a moderate and negative correlation with Ba.

Figure 5Correlogram showing the Spearman correlation between the medians of pairs of stream water physical-chemical parameters and solute concentrations for the 20 sampling sites monitored within the Cube River catchment shown in Table 3. Circles are shown only when the correlation is statistically significant (p value < 0.05). Colour intensity and the shaded area of each circle represent the absolute value of the corresponding correlation. Positive correlations are displayed in blue and negative correlations are shown in red. EC: electrical conductivity, Alk: Alkalinity, T: Temperature, DO: dissolved oxygen, COD: chemical oxygen demand, and TOC: total organic carbon.

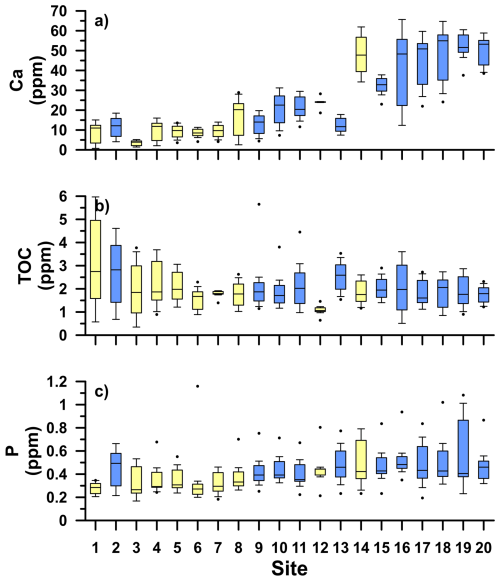

Considering the relatively large number of geochemical parameters analysed in this study and the degree of correlation among them, in the following, we show and describe the spatial variability of water chemistry along the Cube River using three representative parameters of the geologic, biologic, and land use characteristics of the study area for brevity (e.g. Peña et al., 2023). Given the geogenic nature of Ca in dominating calcite veins in the Viche geological formation, its concentration was used to analyse how the geology from both formations (i.e. Playa Rica and Viche) affects stream water chemistry. Because of the biogenic nature of TOC and the potential presence of organic matter in darkish shale dominating the Playa Rica geological formation, TOC was used to assess the effects of forest degradation in the study area. Since the addition of low-cost phosphate rock-based fertilizers is preferred in local cultivation practices due to the acidic nature of the local soil, the concentration of P was used as an indicator of how changes in land use due to anthropogenic activities could potentially affect the hydrological behaviour and chemical characteristics of water at the study site.

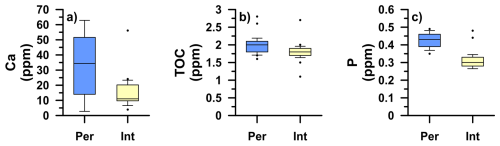

Ca concentrations varied between 3.9 and 54.9 ppm (Table 2). The lowest concentrations of Ca were observed in the smallest subcatchments located in the headwaters (S1–S7; Fig. 6a). The largest subcatchments and the catchment outlet (S15–S20) located at the lower part of the study area had the highest Ca concentrations. Between these extremes, medium size subcatchments mainly located in the middle part of the catchment (S8–S13) had intermediate Ca concentrations. Concentrations of TOC ranged between 1.1 and 2.8 ppm (Table 2). The highest TOC concentrations were found at the sampling sites located in the headwaters of the catchment (S1–S7; Fig. 6b). In the middle and lower parts of the catchment TOC concentrations were generally lower than in the headwaters. Although the variation of P across the sampling sites was relatively small, i.e. 0.27 and 0.49 ppm (Table 2), the concentration of P tended to increase from the headwaters to the outlet of the catchment (Fig. 6c), except for subcatchment S2. The Wilcoxon rank sum test indicates that the concentrations of Ca (Fig. 7a) and P (Fig. 7c) are significantly different (p value < 0.05) between intermittent and perennial streams, while no statistically significant difference can be assumed for TOC (p value = 0.18; Fig. 7b).

Figure 6Boxplots of the concentrations of Calcium (Ca), total organic carbon (TOC), and phosphorus (P) across the 20 sampling sites monitored within the Cube River catchment during six monitoring campaigns carried out in 2021. Light yellow and light blue boxplots show the intermittent and perennial streams, respectively. The horizontal lines represent the first, second (median) and third quartiles, the whiskers represent 0.4 times the interquartile range, and the black dots are outliers. In the x axis, the sampling sites are ordered according to the elevation of their outlets, generally corresponding to the sites with the smallest drainage areas to be located at the Cube River headwaters and the sites with the largest drainage areas downstream toward the catchment's outlet (Fig. 1a, Table 1).

Figure 7Boxplots of the concentrations of Calcium (Ca), total organic carbon (TOC), and phosphorus (P) for the intermittent (Int in light yellow) and perennial (Per in light blue) streams monitored within the Cube River catchment during six monitoring campaigns carried out in 2021. The horizontal lines represent the first, second (median) and third quartiles, the whiskers represent 0.4 times the interquartile range, and the black dots are outliers.

4.5 Relationship between landscape features and stream water geochemistry

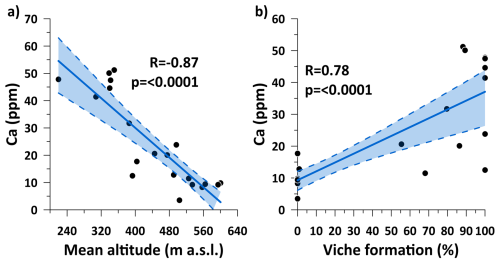

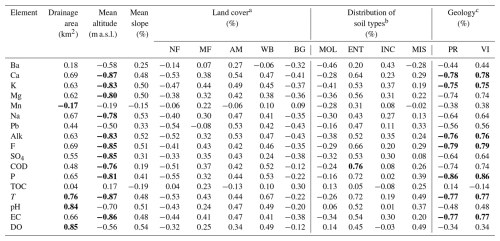

The correlation analysis shows a strong relation between Ca, mean altitude, and geology (Table 3; Fig. 8). The analysis shows a strong, negative, and significant correlation (r = −0.87) between Ca and mean altitude (Fig. 8b) and a strong, positive, and significant correlation (r = 0.78) between Ca and the Viche formation (Fig. 8c); given a strong, negative, and significant correlation (r = −0.79) between mean altitude and the Viche formation (not shown for brevity). Significant but weaker correlations were found between Ca and drainage area (r = 0.69) and between Ca and Entisols (r = 0.64). Weaker and/or non-statistically significant correlations were found between Ca and other landscape features (Table 3). Naturally, all correlations found between Ca and the landscape characteristics hold for other geochemical parameters strongly and moderately correlated with Ca (Fig. 5), including P. The correlation between Ca and the Playa Rica formation is the mirror image of that with the Viche formation shown in Fig. 8c. Land cover, soil type, and mean slope showed weak and non-statistically significant correlations with all solutes (Table 3).

Figure 8Correlation between (a) mean altitude and Ca concentration and (b) between the areal extent of the Viche formation and Ca concentration.

Table 3Spearman correlation coefficients of the relation between the medians of pairs of stream water physical-chemical parameters or solutes' concentrations and main landscape features of the 20 sampling sites monitored within the Cube River catchment. Values in bold indicate correlation coefficients > 0.75 and statistically significant with a p value < 0.01. EC: electrical conductivity, T: Temperature, COD: chemical oxygen demand, Alk: Alkalinity, DO: dissolved oxygen, and TOC: total organic carbon.

a NF: native forest. MF: managed forest. AM: agricultural mosaic (includes crops and pasture for cattle grazing). WB: water body. BG: bare ground. b MOL: Mollisols. ENT: Entisols. INC: Inceptisols. MIS: Miscellaneous. c PR: Playa Rica Formation. VI: Viche Formation.

One of the key questions in catchment hydrology is to determine how the interplay among hydrometeorological conditions, catchment surface and subsurface features, and land use influence streamflow dynamic and flow generation in streams and rivers (Costigan et al., 2016; Godsey and Kirchner, 2014). Addressing this question is especially critical in tropical regions where water availability is drastically affected by changes in land use and climate (Wright et al., 2017). In the following, we discuss the main results and propose a conceptual model of how water flow paths are shaped in these streams by the interaction of hydrometeorological, landscape, and land use conditions.

5.1 Effect of hydrometeorological conditions on streamflow generation in intermittent and perennial tropical streams

High flows with a flashy response during the wet season and low flows with longer recessions during the dry season (Fig. 2a–d) suggest that antecedent wetness conditions are key to drive the hydrological dynamics of streamflow at our study site. These dynamics are supported by the depletion of δ18O in stream water during the wet season (Fig. 3), likely related to the input of high rainfall amounts depleted in the heavy stable isotopes of water (e.g. Mosquera et al., 2016a). Similar hydrological dynamics were observed at an intermittent low relief and highly weathered catchment with a subtropical climate in North Carolina, USA (Zimmer and McGlynn, 2017). However, while in the USA catchment antecedent wetness was controlled by a seasonal change in evapotranspiration with little temporal variability of precipitation; it is likely that the strong seasonal variation of precipitation is the main factor driving the temporal changes in antecedent wetness within the Cube River catchment. The latter likely results from a combined effect of the high rainfall during the wet period and the continuous cloudy and foggy conditions during the dry season. These hydrometeorological conditions likely reduce water losses to the atmosphere via evapotranspiration as has been observed in other tropical montane catchments in Ecuador (e.g. Mosquera et al., 2024; Ochoa-Sánchez et al., 2020). In turn, these conditions help to maintain the streambed humid throughout the year, even in intermittent streams. In addition, the virtually negligible spatial and temporal variation of d-excess across our nested monitoring system throughout the year (Fig. 4c, d) further emphasizes the smaller role evapotranspiration has on the streamflow dynamics of intermittent and perennial streams as compared to precipitation seasonality. This finding is in line with those reported at montane ecosystems at higher elevations in north and south Ecuador, where high air humidity combined with cool to cold temperatures and/or rainy to foggy conditions lead to a diminished influence of evapotranspiration on the stream water isotopic composition (Lahuatte et al., 2022; Mosquera et al., 2016a; Timbe et al., 2014).

5.2 Effect of geology on streamflow dynamics in intermittent and perennial tropical streams

The flashy response of streamflow to rainfall inputs year-round (Fig. 2a, c, e) and the depletion of the isotopic composition of stream water in the headwaters of the Cube River catchment during the wettest period (Fig. 4a) suggest a strong influence of rainfall in water transport in subcatchments feeding intermittent streams (e.g. Mosquera et al., 2020). These observations are supported by the low concentration of major elements and low electrical conductivity in those streams (Figs. 5, 6a), indicating a low contact time of water with minerals in the subsurface. These findings are explained by the low bedrock permeability of the Playa Rica formation that dominates in intermittent subcatchments, which in turn reduces their subsurface water storage capacity. The latter does not only cause a fast response of streamflow to rainfall inputs but also its rapid deactivation as rainfall stops, causing the temporal cessation of flow during sustained periods of little to no rainfall. These patterns are also indicative of a threshold-controlled hydrological response, where streamflow activation only occurs once a critical antecedent moisture or storage condition is exceeded. This behaviour aligns with the concept of threshold-controlled hydrological response (McDonnell, 2003; Sidle et al., 2000), which has been used to explain similar dynamics in other catchments worldwide.

In contrast, the smaller influence of rainfall in streamflow dynamics of perennial streams is evidenced by the longer time spans necessary for those streams to reach peak flow and to return to base flow after rainfall events (Fig. 2b, d, f) compared to intermittent streams. The little to no depletion of the isotopic composition of stream water throughout the year (Fig. 4a, b) and the higher concentration of major elements and higher electrical conductivity for perennial streams (Figs. 5, 6a) support this finding and indicate a higher contact time of water with the underlying bedrock and/or higher reactivity of the geologic material. The latter may result from the high permeability of the Viche formation that dominates in catchments draining perennial streams, providing them with a higher subsurface water storage capacity than catchments where intermittent flow governs (Lazo et al., 2019). The interplay between large inputs of rainfall during the wet period and the high subsurface water storage in perennial catchments may help explain their relatively high flow regulation capacity, i.e. the sustained generation of flow throughout the year, including dry periods with little to no rainfall.

Other field studies focused on evaluating the role of surface and subsurface catchment characteristics in the hydrological behaviour of intermittent hydrological systems have been previously conducted in environments with Mediterranean (Banda et al., 2023), semi-arid (Bourke et al., 2021), continental (Hatley et al., 2023), and tropical savannah (Farrick and Branfireun, 2015) climates. Those studies concluded that bedrock permeability plays a key role in streamflow activation and cessation. Our results in a highly seasonal tropical setting support those findings, highlighting the key role catchment geology plays in driving the occurrence of hydrological intermittency in agreement with our second hypothesis. Opposed to these findings from field studies, numerical modelling approaches to investigate streamflow generation in intermittent hydrological systems have mainly focused on assessing the role of topography and/or soils (e.g. Gutiérrez-Jurado et al., 2019; Gutierrez-Jurado et al., 2021; van Meerveld et al., 2019). Therefore, future modelling studies should carefully consider catchments' geological features to obtain a sound understanding of streamflow generation in intermittent hydrological systems (Mimeau et al., 2024; Shanafield et al., 2021).

Effective conservation and protection efforts currently target the Cube River catchment headwaters where the last plots of primary and secondary tropical Chocó Forest remain. Considering the importance of the middle and lower parts of the catchment whose geological features allow for continuous flow generation that maintains the consequent ecosystem services downstream, conservation efforts should transcend into securing groundwater replenishment and streamflow generation as part of future landscape conservation plans.

5.3 Effect of land use on the hydrology of an intermittent system of tropical streams

Despite the large legacy of anthropogenic impacts due to deforestation and cultivation (Fig. 1b; Molinero et al., 2019), opposed to our first hypothesis, we observed relatively little influence of land use change on the hydrological dynamics of intermittent and perennial streams in the Cube River catchment. The weak and non-statistically significant correlation between geochemical tracers and the land cover of the monitored sites (Table 3) suggests that land use had a small effect on the water flow paths as opposed to the influence of geology. Despite this general trend, higher concentrations of TOC at intermittent streams draining conserved forested areas situated at the upper part of the catchment (Fig. 6b) are likely explained by forest litter accumulation in the ground that is released to streams during rainfall events. On the contrary, the generally lower TOC concentrations found at the middle and lower parts of the Cube River catchment likely result from the long-term legacy of forest loss to cultivation and cattle grazing that in turn affect stream water quality. These inferences are supported by higher concentrations of dissolved carbon from tropical forests in comparison to other land cover including pastures for cattle grazing that have been reported in previous studies in tropical forests (e.g. Meyer et al., 1998; Moeller et al., 2005; Pesántez et al., 2018; Wilcke et al., 2001). It is also worth noting that regardless of the degree of deforestation, we did not observe an extensive occurrence of overland flow throughout the Cube River catchment during the monitoring campaigns.

A seemingly increasing trend in the concentration of P from the headwaters to the main stem of the basin towards its outlet (Fig. 6c) could be attributed to the effect of anthropogenic activities in the study area. The cultivation of exotic species, particularly of cacao and passion fruit plantations, is common across the Cube catchment. Even though this practice is an important economic activity, the low P concentrations in stream water, even at the middle and lower parts of the catchment (Fig. 6c), suggest a relatively low use of organic fertilizers. Nevertheless, future studies in the region should assess the concentrations of other substances used in cultivation, including pesticides, herbicides, and inorganic compounds to assess the impacts of this anthropogenic activity on stream water quality.

5.4 Streamflow generation in intermittent and perennial tropical streams

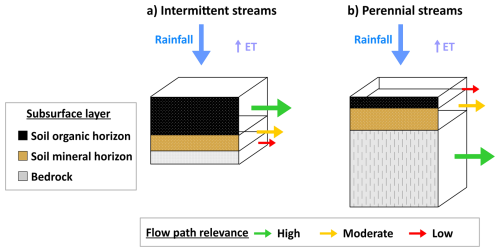

Figure 9 shows a conceptual diagram of the main water flow paths influencing streamflow generation in intermittent and perennial streams of the nested monitoring system of the Cube River catchment. From a process-based perspective, our findings indicate that shallow subsurface flow paths that mobilize water primarily through the thin litter layer (not shown in the diagram for simplicity) and the organic horizon of the soil under primary and secondary forests mainly located at the headwaters of the catchment dominate streamflow generation in intermittent streams (Fig. 9a). Those shallow subsurface water flow paths are favoured by the quasi-impermeable nature of the underlying bedrock of the Playa Rica formation that has low water storage and thus lead to a cessation of flow during the dry season (July–December). Differently, subcatchments draining perennial streams have a high-water storage capacity that is replenished during the wet period (January–May) due to their moderate to high bedrock permeability (Fig. 9b). Such recharge of groundwater helps sustain streamflow generation year-round in perennial streams despite the limited contribution from the litter layer and the organic horizon of the soil that has been substantially reduced or completely removed due to deforestation and cultivation in the Chocó-Darién of northwestern Ecuador. It is also noteworthy that there is little to no influence of surface or overland flow on streamflow generation in both types of streams, demonstrating the key role soil and geology play in streamflow dynamics and flow generation in this intermittent system of tropical streams.

Figure 9Conceptual model of subsurface water flow paths generating streamflow in (a) intermittent and (b) perennial tropical streams at the Cube River catchment, northern Ecuador. The white surface at the top of the boxes represents the surface at the ground level. The size of the coloured boxes representing the soil and bedrock subsurface layers indicates their relative capacity to store water below ground. The dashed vertical lines in the bedrock layer of panel (b) denote the high bedrock permeability of the geology at subcatchments draining perennial streams, as opposed to the almost impermeable bedrock underlying intermittent subcatchments depicted in (a). Overland flow has not been observed in intermittent or perennial streams during field sampling campaigns, and thus, such a streamflow generation mechanism is neglected in the conceptual diagrams. The size and colour of the horizontal arrows represent the relative relevance of various water flow paths influencing streamflow generation.

One of the key questions in catchment hydrology is to determine the factors influencing streamflow dynamics and runoff generation. Our nested monitoring approach comprising 20 spatially distributed streams (< 1–159 km2) within the Cube River catchment allowed us to identify how hydrometeorological conditions and landscape biophysical characteristics influence the hydrological behaviour in intermittent and perennial streams in a biodiversity hotspot on the Ecuadorian forest of the Chocó-Darién ecoregion. Hydrological intermittency is driven by antecedent wetness because of the strong seasonality of precipitation. Nevertheless, the streambed of catchments draining intermittent streams remains moist even when surface water stops flowing given that evapotranspiration is reduced due to the continuous cloudy and foggy conditions during the dry season. Different from intermittent hydrological systems elsewhere, the persistence of moist microhabitats in intermittent tropical forest streams could sustain biological communities and interactions even during dry periods. Our analysis also indicates that the bedrock permeability of the geological formations found in the study area is the most important factor influencing streamflow generation. Our findings supported in a multimethod approach are key to highlighting the importance of carrying out detailed spatially distributed measurements across seasons to unravel the factors influencing the activation of different water flow paths and achieving a sound mechanistic understanding of flow processes in intermittent hydrological systems. While hydrometric data identifies differences in hydrological dynamics between intermittent and perennial streams, isotopic and geochemical data permits defining how water is transported via surface and subsurface water flow paths. Complementarily, the relation between biophysical landscape characteristics and geochemical signals across the nested system helps to define how intrinsic landscape characteristics influence the catchment's hydrological behaviour. The results of this research conducted within the Chocó-Darien ecoregion provide a template for hydrological assessment in places where data is limited. Locally, our findings provide key information for sustainable water management and climate change adaptation in the ecoregion. Beyond this, the study highlights the relevance of considering the landscape subsurface characteristics in the hydrological modelling of intermittent systems of streams. Taking advantage of the demonstrated potential of isotopic and geochemical tracers to investigate streamflow processes in this tropical hydrological system, further hydrological investigations could be targeted to determine the source and age of stream water. In addition, future studies in the region should assess how the identified streamflow dynamics and differences in water flow paths between intermittent and perennial streams influence biological and ecological processes in the ecoregion. Obtaining this information is crucial for improving the management and conservation of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and biodiversity in the region, as well as to secure a sustainable provision of ecosystem services to local communities that are particularly vulnerable to changes in regional land use and global climate patterns. While these findings provide valuable insights into streamflow generation in tropical forest catchments, further research across diverse climatic and geological contexts is needed to assess the broader applicability of this conceptual understanding.

The data used in this study are property of the Deanship of Research and Creativity at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito. These data will become publicly available in accordance with the rules and embargo regulations of the USFQ, but it is not yet known where the data will be hosted (please contact the corresponding authors for updates).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-29-7073-2025-supplement.

Conceptualization and methodology: GMM, ACE. Formal analysis and literature review: GMM. Investigation: GMM, JD. Funding acquisition, project administration, and resources: ACE. Visualization: GMM, JD. Writing – original draft: GMM. Writing – review and editing: all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Giovanny M. Mosquera was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the EU’s Horizon 2020 (grant no. 869226) and the Universidad San Francisco de Quito USFQ through the project “Securing biodiversity, functional integrity and ecosystem services in DRYing riVER networks project (DRYvER)”. We thank the Ecuadorian Ministry of Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition (MAATE) and particularly to the Reserva Ecological Mache-Chindul REMACH for providing research permits to conduct this study (MAAE-ARSFC-2020-1057). We thank the Ecuadorian National Agency of Hydrology and Meteorology (INAMHI) for providing historical precipitation data of the study region. We thank the DRYvER project team, especially Dr. Thibault Datry, for their advice in sampling design and methods to setup the monitoring scheme. We also thank Carla Villamarín, Segundo Chimbolema, Ricardo Jaramillo, Diego Mosquera, and Karla Barragán for their fieldwork support, Christian Suárez for contributing to the spatial analyses, Melany Ruiz-Urigüen and Natalia Carpintero for assessment in laboratory analyses, and two anonymous reviewers for providing feedback on earlier version of the article. Finally, we also thank the logistical and field support of the staff of the Fundación para la Conservación de los Andes Tropicales (FCAT), particularly to Domingo Cabrera, Julio Loor, Darío Cantos, Luís Zambrano, Jorge Olivo, Carlos Aulestia, and Luis Carrasco.

This research was funded by the EU's Horizon 2020 (grant no. 869226) and the Universidad San Francisco de Quito USFQ through the DRYvER project.

This paper was edited by Markus Weiler and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Akoglu, H.: User's guide to correlation coefficients, Turk. J. Emerg. Med., 18, 91–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TJEM.2018.08.001, 2018.

APHA: Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 22nd edn., edited by: Rice, E. W., Baird, R. B., Eaton, A. D., and Clesceri, L. S., American Public Health Association (APHA), American Water Works Association (AWWA) and Water Environment Federation (WEF), Washington, D.C., USA, ISBN 978-0875530130, 2012.

APHA: Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 24th edn., edited by: Lipps, W. C., Braun-Howland, E. B., and Baxter, T. E., American Public Health Association (APHA), American Water Works Association (AWWA) and Water Environment Federation (WEF), ISBN 978-0-87553-299-8, 2023.

Asano, Y., Uchida, T., and Ohte, N.: Residence times and flow paths of water in steep unchannelled catchments, Tanakami, Japan, J. Hydrol., 261, 173–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(02)00005-7, 2002.

Banda, V. D., Mengistu, H., and Kanyerere, T.: Assessment of catchment scale groundwater-surface water interaction in a non-perennial river system, Heuningnes catchment, South Africa, Sci. Afr., 20, e01614, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCIAF.2023.E01614, 2023.

Barthold, F., Wu, J., Vaché, K., Schneider, K., Frede, H.-G., and Breuer, L.: Identification of geographic runoff sources in a data sparse region: hydrological processes and the limitations of tracer-based approaches, Hydrol. Process., 24, 2313–2327, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.7678, 2010.

Bourke, S. A., Degens, B., Searle, J., de Castro Tayer, T., and Rothery, J.: Geological permeability controls streamflow generation in a remote, ungauged, semi-arid drainage system, J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud., 38, 100956, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJRH.2021.100956, 2021.

Correa, A., Windhorst, D., Crespo, P., Célleri, R., Feyen, J., and Breuer, L.: Continuous versus event-based sampling: how many samples are required for deriving general hydrological understanding on Ecuador's páramo region?, Hydrol. Process., 30, 4059–4073, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.10975, 2016.

Correa, A., Windhorst, D., Tetzlaff, D., Crespo, P., Célleri, R., Feyen, J., and Breuer, L.: Temporal dynamics in dominant runoff sources and flow paths in the Andean Páramo, Water Resour. Res., 53, 5998–6017, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016WR020187, 2017.

Costigan, K. H., Jaeger, K. L., Goss, C. W., Fritz, K. M., and Goebel, P. C.: Understanding controls on flow permanence in intermittent rivers to aid ecological research: integrating meteorology, geology and land cover, Ecohydrology, 9, 1141–1153, https://doi.org/10.1002/ECO.1712, 2016.

Costigan, K. H., Kennard, M. J., Leigh, C., Sauquet, E., Datry, T., and Boulton, A. J.: Flow Regimes in Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams, Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams: Ecology and Management, 51–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803835-2.00003-6, 2017.

Craig, H.: Isotopic Variations in Meteoric Waters, Science, 133, 1702–1703, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.133.3465.1702, 1961.

Cuesta, F., Peralvo, M., Merino-Viteri, A., Bustamante, M., Baquero, F., Freile, J. F., Muriel, P., and Torres-Carvajal, O.: Priority areas for biodiversity conservation in mainland Ecuador, Neotrop. Biodivers., 3, 93–106, https://doi.org/10.1080/23766808.2017.1295705, 2017.

Datry, T., Allen, D., Argelich, R., Barquin, J., Bonada, N., Boulton, A., Branger, F., Cai, Y., Cañedo-Argüelles, M., Cid, N., Csabai, Z., Dallimer, M., Araújo, J. C. de, Declerck, S., Dekker, T., Döll, P., Encalada, A., Forcellini, M., Foulquier, A., Heino, J., Jabot, F., Keszler, P., Kopperoinen, L., Kralisch, S., Künne, A., Lamouroux, N., Lauvernet, C., Lehtoranta, V., Loskotová, B., Marcé, R., Ortega, J. M., Matauschek, C., Miliša, M., Mogyorósi, S., Moya, N., Schmied, H. M., Munné, A., Munoz, F., Mykrä, H., Pal, I., Paloniemi, R., Pařil, P., Pengal, P., Pernecker, B., Polášek, M., Rezende, C., Sabater, S., Sarremejane, R., Schmidt, G., Domis, L. S., Singer, G., Suárez, E., Talluto, M., Teurlincx, S., Trautmann, T., Truchy, A., Tyllianakis, E., Väisänen, S., Varumo, L., Vidal, J.-P., Vilmi, A., and Vinyoles, D.: Securing Biodiversity, Functional Integrity, and Ecosystem Services in Drying River Networks (DRYvER), Research Ideas and Outcomes, 7, e77750, https://doi.org/10.3897/RIO.7.E77750, 2021.

Dansgaard, W.: Stable isotopes in precipitation, Tellus A, 16, 436–468, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusa.v16i4.8993, 1964.

DIIEA: Geology and Geomorphology [geographic layers], Dirección de Información, Investigación y Educación Ambiental (DIIEA), 2010.

Dinerstein, E., Olson, D., Joshi, A., Vynne, C., Burgess, N. D., Wikramanayake, E., Hahn, N., Palminteri, S., Hedao, P., Noss, R., Hansen, M., Locke, H., Ellis, E. C., Jones, B., Barber, C. V., Hayes, R., Kormos, C., Martin, V., Crist, E., Sechrest, W., Price, L., Baillie, J. E. M., Weeden, D., Suckling, K., Davis, C., Sizer, N., Moore, R., Thau, D., Birch, T., Potapov, P., Turubanova, S., Tyukavina, A., De Souza, N., Pintea, L., Brito, J. C., Llewellyn, O. A., Miller, A. G., Patzelt, A., Ghazanfar, S. A., Timberlake, J., Klöser, H., Shennan-Farpón, Y., Kindt, R., Lillesø, J. P. B., Van Breugel, P., Graudal, L., Voge, M., Al-Shammari, K. F., and Saleem, M.: An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm, Bioscience, 67, 534–545, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix014, 2017.

Dingman, S. L.: Physical hydrology, 3rd edn., Waveland Press, Inc., Long Grove, IL, 643 pp., ISBN 978-1478611189, 2015.

Dohman, J. M., Godsey, S. E., and Hale, R. L.: Three-Dimensional Subsurface Flow Path Controls on Flow Permanence, Water Resour. Res., 57, e2020WR028270, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR028270, 2021.

EURACHEM/CITAC: Quantifying Uncertainty in Analytical Measurement, 3rd edn., edited by: Ellison, S. L. R. and Williams, A., EURACHEM, 133 pp., ISBN 978-0-948926-30-3, 2012.

Fagua, J. C. and Ramsey, R. D.: Geospatial modeling of land cover change in the Chocó-Darien global ecoregion of South America; One of most biodiverse and rainy areas in the world, PLoS One, 14, e0211324, https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0211324, 2019.

Farrick, K. K. and Branfireun, B. A.: Flowpaths, source water contributions and water residence times in a Mexican tropical dry forest catchment, J. Hydrol., 529, 854–865, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.08.059, 2015.

Godsey, S. E. and Kirchner, J. W.: Dynamic, discontinuous stream networks: hydrologically driven variations in active drainage density, flowing channels and stream order, Hydrol. Process., 28, 5791–5803, https://doi.org/10.1002/HYP.10310, 2014.

Gutiérrez-Jurado, K. Y., Partington, D., Batelaan, O., Cook, P., and Shanafield, M.: What Triggers Streamflow for Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams in Low-Gradient Catchments in Mediterranean Climates, Water Resour. Res., 55, 9926–9946, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR025041, 2019.

Gutierrez-Jurado, K. Y., Partington, D., and Shanafield, M.: Taking theory to the field: streamflow generation mechanisms in an intermittent Mediterranean catchment, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 25, 4299–4317, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-4299-2021, 2021.

Hatley, C. M., Armijo, B., Andrews, K., Anhold, C., Nippert, J. B., and Kirk, M. F.: Intermittent streamflow generation in a merokarst headwater catchment, Environmental Science: Advances, 2, 115–131, https://doi.org/10.1039/D2VA00191H, 2023.

Inamdar, S., Dhillon, G., Singh, S., Dutta, S., Levia, D., Scott, D., Mitchell, M., Van Stan, J., and McHale, P.: Temporal variation in end-member chemistry and its influence on runoff mixing patterns in a forested, Piedmont catchment, Water Resour. Res., 49, 1828–1844, https://doi.org/10.1002/wrcr.20158, 2013.

Jachens, E. R., Roques, C., Rupp, D. E., and Selker, J. S.: Streamflow Recession Analysis Using Water Height, Water Resour. Res., 56, e2020WR027091, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR027091, 2020.

Jacobs, S. R., Timbe, E., Weeser, B., Rufino, M. C., Butterbach-Bahl, K., and Breuer, L.: Assessment of hydrological pathways in East African montane catchments under different land use, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 4981–5000, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-4981-2018, 2018.

Kirchner, J. W., Godsey, S. E., Solomon, M., Osterhuber, R., McConnell, J. R., and Penna, D.: The pulse of a montane ecosystem: coupling between daily cycles in solar flux, snowmelt, transpiration, groundwater, and streamflow at Sagehen Creek and Independence Creek, Sierra Nevada, USA, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 24, 5095–5123, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-24-5095-2020, 2020.

Lahuatte, B., Mosquera, G. M., Páez-Bimos, S., Calispa, M., Vanacker, V., Zapata-Ríos, X., Muñoz, T., and Crespo, P.: Delineation of water flow paths in a tropical Andean headwater catchment with deep soils and permeable bedrock, Hydrol. Process., 36, e14725, https://doi.org/10.1002/HYP.14725, 2022.

Laudon, H., Seibert, J., Köhler, S., and Bishop, K.: Hydrological flow paths during snowmelt: Congruence between hydrometric measurements and oxygen 18 in meltwater, soil water, and runoff, Water Resour. Res, 40, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003WR002455, 2004.

Lazo, P. X., Mosquera, G. M., McDonnell, J. J., and Crespo, P.: The role of vegetation, soils, and precipitation on water storage and hydrological services in Andean Páramo catchments, J. Hydrol., 572, 805–819, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.03.050, 2019.

Leibundgut, C., Maloszewski, P., and Külls, C.: Tracers in hydrology, Wiley InterScience (Online service), Wiley-Blackwell, 415 pp., ISBN 978-0-470-51885-4, 2009.

Leigh, C., Boulton, A. J., Courtwright, J. L., Fritz, K., May, C. L., Walker, R. H., and Datry, T.: Ecological research and management of intermittent rivers: an historical review and future directions, Freshw Biol, 61, 1181–1199, https://doi.org/10.1111/FWB.12646, 2016.

Liu, F., Williams, M., and Caine, N.: Source waters and flow paths in an alpine catchment, Colorado Front Range, United States, Water Resour. Res., 40, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004WR003076, 2004.

MAATE: Land Cover and Use Map of Ecuador [geographic layer], Geovisor of the Ecuadorian Ministry of the Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition (MAATE), http://ide.ambiente.gob.ec/mapainteractivo/ (last access: 11 November 2023), 2022.

MAG: Geopedological Unit [geographic layer], Geovisor of the Ecuadorian Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAG), http://geoportal.agricultura.gob.ec/ (last access: 11 November 2023), 2019.

McDonnell, J. J.: Where does water go when it rains? Moving beyond the variable source area concept of rainfall-runoff response, Hydrol. Process., 17, 1869–1875, https://doi.org/10.1002/HYP.5132, 2003.

McDonnell, J. J. and Kendall, C.: Isotope tracers in hydrology, Eos Transactions American Geophysical Union, 73, 260–260, https://doi.org/10.1029/91EO00214, 1992.

McGuire, K. J., McDonnell, J. J., Weiler, M., Kendall, C., McGlynn, B. L., Welker, J. M., and Seibert, J.: The role of topography on catchment-scale water residence time, Water Resour Res, 41, W05002, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004WR003657, 2005.

Messager, M. L., Lehner, B., Cockburn, C., Lamouroux, N., Pella, H., Snelder, T., Tockner, K., Trautmann, T., Watt, C., and Datry, T.: Global prevalence of non-perennial rivers and streams, Nature, 594, 391–397, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03565-5, 2021.

Meyer, J. L., Wallace, J. B., and Eggert, S. L.: Leaf litter as a source of dissolved organic carbon in streams, Ecosystems, 1, 240–249, https://doi.org/10.1007/s100219900019, 1998.

Mimeau, L., Künne, A., Branger, F., Kralisch, S., Devers, A., and Vidal, J.-P.: Flow intermittence prediction using a hybrid hydrological modelling approach: influence of observed intermittence data on the training of a random forest model, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 28, 851–871, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-28-851-2024, 2024.

Moeller, A., Kaiser, K., and Guggenberger, G.: Dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen in precipitation, throughfall, soil solution, and stream water of the tropical highlands in northern Thailand, J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sc., 168, 649–659, https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200521804, 2005.

Molinero, J., Barrado, M., Guijarro, M., Ortiz, M., Carnicer, O., and Zuazagoitia, D.: The Teaone river: A snapshot of a tropical river from the coastal region of Ecuador, Limnetica, 38, 587–605, https://doi.org/10.23818/LIMN.38.34, 2019.

Mosquera, G. M., Lazo, P. X., Célleri, R., Wilcox, B. P., and Crespo, P.: Runoff from tropical alpine grasslands increases with areal extent of wetlands, Catena, 125, 120–128, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2014.10.010, 2015.

Mosquera, G. M., Célleri, R., Lazo, P. X., Vaché, K. B., Perakis, S. S., and Crespo, P.: Combined Use of Isotopic and Hydrometric Data to Conceptualize Ecohydrological Processes in a High-Elevation Tropical Ecosystem, Hydrol. Process., 30, 2930–2947, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.10927, 2016a.

Mosquera, G. M., Segura, C., Vaché, K. B., Windhorst, D., Breuer, L., and Crespo, P.: Insights into the water mean transit time in a high-elevation tropical ecosystem, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 20, 2987–3004, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-20-2987-2016, 2016b.