the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Drought onset and propagation into soil moisture and grassland vegetation responses during the 2012–2019 major drought in Southern California

Maria Magdalena Warter

Michael Bliss Singer

Mark O. Cuthbert

Dar Roberts

Kelly K. Caylor

Romy Sabathier

John Stella

Despite clear signals of regional impacts of the recent severe drought in California, e.g., within Californian Central Valley groundwater storage and Sierra Nevada forests, our understanding of how this drought affected soil moisture and vegetation responses in lowland grasslands is limited. In order to better understand the resulting vulnerability of these landscapes to fire and ecosystem degradation, we aimed to generalize drought-induced changes in subsurface soil moisture and to explore its effects within grassland ecosystems of Southern California. We used a high-resolution in situ dataset of climate and soil moisture from two grassland sites (coastal and inland), alongside greenness (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) data from Landsat imagery, to explore drought dynamics in environments with similar precipitation but contrasting evaporative demand over the period 2008–2019. We show that negative impacts of prolonged precipitation deficits on vegetation at the coastal site were buffered by fog and moderate temperatures. During the drought, the Santa Barbara region experienced an early onset of the dry season in mid-March instead of April, resulting in premature senescence of grasses by mid-April. We developed a parsimonious soil moisture balance model that captures dynamic vegetation–evapotranspiration feedbacks and analyzed the links between climate, soil moisture, and vegetation greenness over several years of simulated drought conditions, exploring the impacts of plausible climate change scenarios that reflect changes to precipitation amounts, their seasonal distribution, and evaporative demand. The redistribution of precipitation over a shortened rainy season highlighted a strong coupling of evapotranspiration to incoming precipitation at the coastal site, while the lower water-holding capacity of soils at the inland site resulted in additional drainage occurring under this scenario. The loss of spring rains due to a shortening of the rainy season also revealed a greater impact on the inland site, suggesting less resilience to low moisture at a time when plant development is about to start. The results also suggest that the coastal site would suffer disproportionally from extended dry periods, effectively driving these areas into more extreme drought than previously seen. These sensitivities suggest potential future increases in the risk of wildfires under climate change, as well as increased grassland ecosystem vulnerability.

- Article

(5104 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(337 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The severe drought between 2012 and 2016 affected most of the state of California (USA), resulting in substantial impacts on water resources and ecosystems (NDMC, 2020; Prugh et al., 2018; Shukla et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2015), yet current understanding of the California drought's impacts is based on research within particular regions and biomes. Consecutive years of low precipitation, above-average temperatures, and extremely dry conditions (meteorological drought) over this drought period resulted in severely reduced snowpack, streamflow, and groundwater storage (hydrological drought); periods of increased soil moisture deficit; and elevated vegetative stress (agricultural drought), with dramatic effects on upland forest dieback and tree mortality (Berg and Hall, 2017; Diffenbaugh et al., 2015; Swain et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2015). Although, the entire state experienced drought effects to some degree, there were notable differences in vegetation responses between Northern California and Southern California (Dong et al., 2019). In upland forests within the Sierra Nevada, there was large-scale canopy water loss and forest dieback as a result of the accumulated precipitation deficits, increased evaporative demand, and soil moisture drying (Asner et al., 2016; Fettig et al., 2019; Goulden and Bales, 2019), while there was only a documented decline in vegetation greenness in Southern California (Dong et al., 2019). Little is known about the propagation of drought from the atmosphere into soil moisture or its associated effects on vegetation in lowland areas, especially within water-limited regions where grasses and shrubs dominate the landscape. These lowland water-limited grassland ecosystems exhibit complex relationships between vegetation and water availability that affect the spatial pattern and extent of different vegetation types, as well as the relative responses of different species to drought stress (Caylor et al., 2006, 2009; D'Odorico et al., 2007; Okin et al., 2018). The progression of climate change and its potential impacts on the water balance demand a better understanding of how mean climate (temperature, precipitation) and soil water availability drive vegetation dynamics in lowland grasslands. The increasing loss of grassland ecosystems increases the threat of overall land degradation and encroachment of invasive species, which ultimately feeds back into heightened vulnerability of these ecosystems to water deficits under climate change (Gremer et al., 2015; Lian et al., 2020). In this study, we explore the links between climate, soil moisture, and vegetation during the recent California drought and analyze the potential consequences of future climate scenarios to advance our understanding of dynamic drought responses within vegetation in lowland grassland ecosystems.

Soil moisture is essential for plant growth and health; accordingly, there are strong seasonal responses of vegetation to temperature and precipitation changes (Coates et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2010). Grassland ecosystems throughout Southern California naturally exhibit green and senescent (brown) periods each year, due to the region's strong Mediterranean climate, which makes these ecosystems naturally fire prone during the dry season. Although such fires are part of the natural ecosystems of Southern California, they are also capable of encroaching on inhabited areas with disastrous effects (e.g., huge areas are currently burning due to fires spreading through grasslands in many western states at the time of submitting this article). Rising soil moisture deficits due to meteorological droughts can cause early senescence of vegetation and thus priming grasslands for intense wildfires while also modifying species composition, runoff responses, and nutrient dynamics (Lian et al., 2020; Ludwig et al., 2005; McDowell et al., 2008; Michaelides et al., 2009). In recent decades, wildfire extent has increased substantially in Southern California, due to increased evaporative demand, reduced snowpack in mountainous areas, and loss of dry season precipitation. Under these conditions native grasslands become more susceptible to non-native species invasion, and native sage scrub is lost (Singh and Meyer, 2020; Williams et al., 2019). The most destructive fires often occur at the end of the dry season when moisture content of live and dead fuels is severely reduced after months of warm and dry weather (Keeley and Syphard, 2016; Williams et al., 2019). One example is the cascading effects of wildfire, subsequent rains, and debris flows that devastated Montecito in Santa Barbara County in 2018 (Oakley et al., 2018). Significant changes in rainfall intensity are expected around the globe (Trenberth, 2011; Westra et al., 2014), even in dryland areas (Singer and Michaelides, 2017; Singer et al., 2018), where we might expect drier spring and fall periods and an increase in subsequent dry years throughout many locations in California (Pierce et al., 2018). Such climatic conditions would likely further increase fuel aridity and wildfire potential and lead to a shift in future fire regimes with more frequent and intense wildfires throughout the western US (Abatzoglou and Williams, 2016; Williams et al., 2019) and thus potentially increasing the overall vulnerability of grasslands and surrounding communities.

Advances in remote sensing have provided new, spatially explicit observations of vegetation dynamics and moisture availability (Coates et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2012; Small et al., 2018). Additionally, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) developed a well-established approach to estimate soil moisture for agricultural purposes (Allen et al., 1998), which has also proven to be useful for other non-agricultural applications (Cuthbert et al., 2013, 2019). This simple soil moisture balance approach, combined with remote sensing data, shows promise for understanding drought propagation into soil moisture. Soil moisture is our key drought metric of interest, as it inherently links precipitation, evaporative demand, and vegetation greenness as measured by Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). The timing of vegetation growth and die-off is strongly related to seasonal fluctuations in water availability to plants, especially in annual grasslands, so the assessment of soil moisture and greenness is essential for vegetation drought monitoring (Liu et al., 2012; Small et al., 2018).

Currently, the vulnerability of California grasslands to future climate change is classified as “moderately high”, with some studies estimating a substantial loss of grassland habitats by the end of the 21st century (Thorne et al., 2016; Wilkening et al., 2019). The greater vulnerability of vegetation to drought in Southern California (compared to Northern California) and a continuing trend of aridification in this region will likely pose a compounding challenge to lowland vegetation and water resources throughout the entire US southwest (Dong et al., 2019). Increases in temperatures and evaporative demand may shift soil moisture conditions towards drier conditions, thereby increasing the risk of extreme droughts and stronger summer heat waves (Ault et al., 2016; Lian et al., 2020). Although many grass species are adapted to dry periods, a better understanding of the responses of lowland grassland vegetation to time-varying soil moisture stress associated with precipitation variability induced by climate change is essential to advance our knowledge and capabilities to mitigate the potential negative impacts of drought on these ecosystems.

In this study we build upon the FAO soil moisture modeling approach by including dynamic interactions between vegetation and climate through the incorporation of remotely sensed data. We use the model to investigate the evolution of soil moisture during the recent California drought and under several potential future drought scenarios. Our primary objective was to understand the broader patterns in the soil moisture and vegetation responses to climate forcing and to advance the understanding of how drought propagates through shallow soil moisture to affect lowland grassland vegetation. We investigated (i) how local soil moisture evolved over the recent California drought; (ii) how changes in precipitation amounts and timing affected soil moisture dynamics and grassland vegetation; and (iii) how soil moisture might respond to more prolonged dry periods under plausible climate scenarios. We employed NDVI from Landsat alongside long-term high-resolution meteorological and soil moisture data from two distinct grassland locations in Santa Barbara County with contrasting climate conditions due to orography and air flow affecting evaporative demand: a coastal and an inland site. We used these data to parameterize a simple parsimonious single-layer soil moisture balance model for generalizing the impact of climate on plant-available water in grassland ecosystems. We also developed a leading indicator of greenness based on available precipitation, which is used in our modeling framework to explore the effects of plausible climate change scenarios.

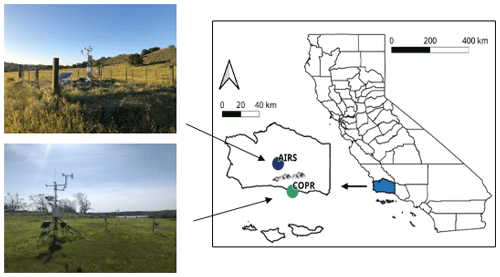

2.1 Study sites

In this study, we focused on two grasslands sites in Santa Barbara County in Southern California. The natural geography of this region is characterized by coastal plains, oak woodlands, and a rugged mountain range (Roberts et al., 2010). Two sites were chosen from a network of several sites as they had the best data availability spanning over 10 years, while also representing the diverse geography of the region: a coastal grassland plain and an inland grassland site, north of the Santa Ynez Mountains (Fig. 1). Both sites are characterized by a Mediterranean climate, with strongly seasonal precipitation during the winter and prolonged dry periods in the summer. The majority of precipitation falls between November and March, with an average of 352 mm (coastal) and 314 mm (inland) per water year (October–September). Previous studies have shown that growing season water availability strongly controls annual growth cycles and senescence of vegetation at these sites (Liu et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2010).

Figure 1Location of stations in Santa Barbara County showing the coastal grassland site (COPR, green), with a marine microclimate, and the semiarid inland grassland site (AIRS, blue) north of the Santa Ynez mountain range.

The coastal site is located at the Coal Oil Point Reserve at an elevation of 6 m a.s.l. The dominant vegetation at this site is classified as introduced European grassland with several non-native species, including a range of annual grasses and forbs. Species vary significantly between years, due to rainfall variability, however wild oat grass (Avena fatua) dominates the landscape. The inland site is situated at Sedgwick Reserve Airstrip in the Santa Ynez Valley on the University of California's Sedgwick Reserve at an elevation of 381 m a.s.l. The site is an open grassland, and neither site is grazed. There is a higher species variability here than at the coastal site (mostly in the form of forbs) and includes several annual non-native grasses, such as various brome grasses (Bromus hordeaceaus L., Bromus diandrus) and also wild oat. The inland site is situated in a relatively dry valley in the rain shadow of the Santa Ynez mountain range, resulting in a higher evaporative demand during the summer due to higher temperatures (May–August average 28.5 ∘C) compared to the coastal site (May–August average 20.6 ∘C). Temperatures are more moderate at the coastal site, due to the presence of cooler, moister ocean air and coastal stratus clouds and thus lower insolation, enhanced by a coastal current, all of which reduce the overall evaporative demand (Roberts et al., 2010). The coastal and inland sites also vary in soil textural properties and water-holding capacity, with soil types varying from clay loam at the coastal site to loam at the inland site, where there are distinctly higher sand contents (Table S1 in the Supplement). Soil samples from several depths were taken at the time of sensor installation in 2007 by University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB), and texture, porosity, field capacity, and wilting point measurements were determined in the lab.

2.2 Historical climate

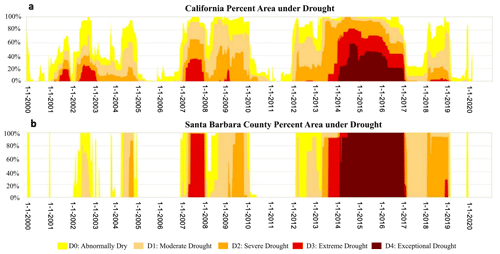

The United States Drought Monitor (USDM; https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/, last access: 12 February 2021) defines drought as a moisture deficit of such severity that it causes social, environmental, or economic effects. The USDM identifies and labels areas of drought within the United States based on a semiquantitative intensity scale, derived from a combination of key indicators and information on soil moisture, precipitation, streamflow, and drought severity, along with local condition and impact reports and ranges from D0 (abnormally dry) to D4 (exceptional drought) (NDMC, 2020). The recent multiyear drought affected the majority of the state of California between 2012–2016 (e.g., Dong et al., 2019) at varying levels according to the USDM (Fig. 2a), whereas Santa Barbara County was under continuous drought conditions much longer (until 2019) (Fig. 2b). The county was under “extreme” (D3) to “exceptional” (D4) drought from mid-2013 until early 2017, with the entire area remaining in the most severe category for several years. By spring 2017 the county was still under “moderate” drought (D1), following a single wet winter season. However, the accumulated moisture deficit was so high after several years of exceptional drought conditions that the state reverted to a state of “severe” drought (D2) in 2018 after another abnormally dry year. The region finally came out of the drought completely in early 2019 after the wettest rainy season since 2005. Based on the drought designations from the USDM, we defined the following three drought categories: (i) no drought (January 2010–March 2012, February–October 2019 end of data), (ii) moderate drought including periods of D0 and D1, and (iii) extreme drought including periods of D2–D4. We apply the three different categories to characterize the meteorology of the drought and to assess the changes in mean climate and vegetation responses.

Figure 2Time series of (a) percentage area of California under drought and (b) percentage area of Santa Barbara County under drought. (The US Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska Lincoln, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map courtesy of NDMC.)

2.3 Meteorological and soil moisture data

We used meteorological and soil moisture data from a network of several sites where data have been continuously recorded at 15 min resolution since 2007 by UCSB for educational purposes (Roberts et al., 2010). The data are publicly available and continuously updated (https://ideas.geog.ucsb.edu/, last access: 10 October 2019). Meteorological data from each station include air temperature (T), relative humidity (RH), net radiation, wind speed and direction, and precipitation (P) among others. For each site, we summarized temperature and humidity with daily maximum daytime values and precipitation with daily totals to define the meteorology during our study period. We used other variables from the dataset, such as soil temperature, wind speed, and net radiation, to estimate the necessary parameters and calculate the reference evapotranspiration (ET0) via the Penman–Monteith approach (Allen et al., 1998). We analyzed the date of onset (day of the year of last recorded precipitation for more than 3 months) and length of the dry season for each year and compared the timing between moderate drought, extreme drought, and non-drought periods. Two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) tests and Pearson's correlation were used to determine statistical differences between these periods and to quantify correlations between variables, such as T, RH, P, ET0, available P (P–ET0 losses), soil moisture saturation, and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI).

Volumetric soil water content and soil temperature were measured using in situ probes (Stevens Hydro Probe II, Stevens Water Monitoring Systems Inc., Portland) at three different depths (10, 20, and 50 cm at the coastal site and 15, 23, and 46 cm at the inland site) (Roberts et al., 2010). For the purposes of this study, we use the shallowest soil moisture at each site, in order to capture the precipitation and evapotranspiration dynamics of the shallow soil horizon we are investigating, which comprises the majority of the moisture availability to grasses. We present historical soil moisture as relative saturation levels, ranging from dry (0 %) to fully saturated (100 %), defined as the ratio of volumetric moisture content to the volume of pore space (porosity). This allows for a direct comparison of soil moisture between the two sites, considering the differing soil textural properties. While the data recovery for both meteorological stations was continuous for the period of interest, the soil moisture probes at the inland site experienced significant data loss between 2016–2018, due to battery and sensor failure; these gaps in the data are indicated in our results.

2.4 Normalized difference vegetation index

Vegetation indices from remote sensing have been widely used to monitor the effects of drought on vegetation, as well as the links between precipitation, soil moisture, and plant sensitivity (Dong et al., 2019; Gu et al., 2008; Small et al., 2018). Multispectral indices, such as NDVI, provide good spatial and temporal representation of drought conditions, which can be combined with in situ measurement of soil moisture for a more detailed understanding of drought propagation and drought stress on vegetation (Gu et al., 2008; Okin et al., 2018). To analyze the seasonality and relationship between soil moisture and vegetation for our study period, we used NDVI computed from red and near-infrared surface reflectance data distributed by the USGS for Landsat-5 (Thematic Mapper), Landsat-7 (Enhanced Thematic Mapper), and Landsat-8 (Operational Land Imager) – each with a 16 d acquisition interval and 30 m resolution. Because we are using multiple Landsat instruments, the data from Landsat-5, Landsat-7, and Landsat-8 were homogenized using the approach of Goulden and Bales (2019). If a pixel was cloudy, we removed the whole image to create a consistent time series of all pixels over the sampling area. We defined polygons around the measuring stations to capture a broader area of homogenous grassland vegetation and soil textural properties at the coastal (19 800 m2) and inland site (35 100 m2). The polygons are based on field surveys made during site installation and on NDVI image analysis, delineating regions of relatively homogenous NDVI including only grassland vegetation (no trees). We quantified spatially averaged NDVI over each polygon to obtain a monthly time series for the period January 2008 to October 2019. NDVI, as a function of the red and near-infrared wavelengths, ranges from +1 to −1 and reaches its maximum (saturated) value of 1 in conditions of high plant vigor and photosynthetic activity, most common in forested areas and cultivated fields. Low or negative values are more representative of bare ground, senescent vegetation, or water surfaces (Gillespie et al., 2018). Through a pixel-wise visual analysis of NDVI and comparison of different cover types (grassland, bare ground, forest, water) over our grassland sites, we established that in our study area green grassland vegetation is generally represented by values > 0.3, while NDVI values < 0.3 are more indicative of brown or senescent (non-photosynthesizing) vegetation.

2.5 Soil moisture balance model

2.5.1 Model description

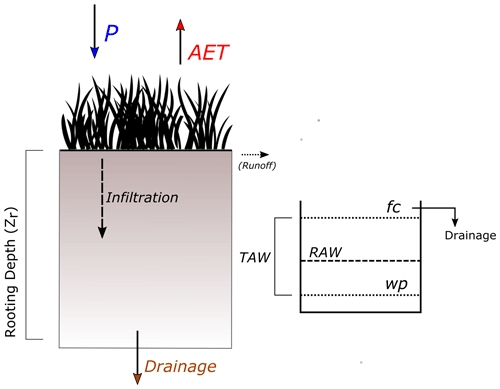

We developed a simple, parsimonious model to better understand the linkages between climate, plant water availability, and plant health and include experimental manipulations of climate variables to explore plausible future climate scenarios. Rather than attempting to model detailed soil moisture processes, we used a simplified soil moisture balance model (SMBM) established by the FAO, which is based on a “bucket” approach (Allen et al., 1998) and is a variant of a code previously developed for estimating groundwater recharge (Cuthbert et al., 2013, 2019). Simple modeling frameworks capable of linking vegetation to water availability can be useful tools to assess past and future ecohydrological dynamics in a range of water-limited environments (Caylor et al., 2009; D'Odorico et al., 2007; Evans et al., 2018; Quichimbo et al., 2020). Therefore, model inputs are kept as simple as possible and include information on soil properties, vegetation cover, and climate (precipitation and the meteorological variables required to estimate reference evapotranspiration (ET0)). Due to the flat topography of our study sites, we assume runoff is zero; thus, precipitation is either infiltrating into the soil or returned to the atmosphere through evapotranspiration. Figure 3 shows a simplified conceptual design of a homogenous soil column and the relevant incoming (P) and outgoing (AET, runoff and drainage) fluxes, as established by Allen et al. (1998). The model uses the concepts of total available water (TAW) and readily available water (RAW), which are dependent on soil textural properties, to estimate the soil moisture deficit and by extension soil moisture content. For this study, information on soil properties was available (Table S1); however, if field measurements are unavailable, typical ranges for field capacity, wilting point, and rooting depths can also be found in the FAO56 manual (Tables 19 and 22 in Allen et al., 1998). The depletion fraction factor (pc) that decreases TAW is generally dependent on vegetation or crop type and was set to a commonly used range between 0.2–0.6 (Allen et al., 1998, Table 22). The SMBM was driven by precipitation from meteorological data and reference evapotranspiration estimated through Penman–Monteith, using meteorological data from the weather stations (Allen et al., 1998). Due to the richness of the IDEAS dataset, variables such as soil temperature, wind speed, and net radiation were available, which allowed us to estimate the necessary parameters such as ground heat flux and conductance, to apply the Penman–Monteith model. Additional parameters in the SMBM are shown in Table S2.

2.5.2 Dynamic vegetation response

Within the SMBM actual evapotranspiration (AET) is estimated using a crop coefficient (kc) as the empirical ratio relating plant ET to a calculated reference ET (ET0) and to account for changes in evaporative demand over a growing season. Previous studies have explored the relationship between multispectral vegetation indices, such as NDVI, and crop coefficients and have applied it successfully to estimate kc at the field scale for different locations and climate conditions (Glenn et al., 2011; Hunsaker et al., 2005). Since kc traditionally does not account for variations in plant growth due to climate variations or uneven water distribution, the alternative use of vegetation indices allows for a more accurate and dynamic estimation of ET (Nagler et al., 2005). NDVI was found to be closely correlated to ET, where maximum ET and maximum NDVI coincide at approximately the same time during a growing season, thus making NDVI a suitable proxy to estimate crop coefficients (Glenn et al., 2011). We use the same linear relationship between NDVI and kc to model a temporally varying crop coefficient derived from vegetation indices to quantify plant ET as follows:

where represents a plant transpiration coefficient, and η is an exponent determined by the relationship of ET0 as measured by Pearson's correlation and the vegetation index used in Eq. (2). VI* is the vegetation index normalized between 0 and 1 to represent bare soil or dead vegetation and fully transpiring and unstressed vegetation, respectively, and calculated as

where NDVImax is the value when ET is maximal, and NDVImin is the ET of bare soil. Actual evapotranspiration under unstressed conditions can then be estimated as

2.5.3 Model implementation

The data were separated into calibration and validation sets, and model performance in each period was evaluated for acceptance or rejection of models. During calibration, model performance was optimized using data from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2014. This time frame was chosen to include the natural variation of soil moisture dynamics, including non-drought and drought period. The model was then tested against data from 1 January 2015 to 30 September 2019. This period also includes natural variations in soil moisture, including the drought, and individual very wet and dry years to account for the possibility of different combinations of parameter values that may all be equally successful at reproducing the observed soil moisture data. We defined the quantitative measures of acceptance or rejection criteria using Kolmogorov–Smirnov (goodness-of-fit) testing to identify parameter combinations that achieve statistically similar (p>0.01) distributions in observed versus simulated soil moisture. The temporal dynamics of soil moisture were evaluated via Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) to identify parameter combinations that adequately simulated the observed soil moisture series (NSE > 0.5). The models accepted during calibration and validation periods were then evaluated via goodness of fit, and the best model and its parameters were used for simulating soil moisture under simple climate change scenarios. We developed an envelope of uncertainty based on Monte Carlo sampling (1000 simulations from a uniform distribution) using known ranges for soil textural properties and general estimates from Allen et al. (1998, Table 22) for rooting depth and depletion fraction and included ±1 SD (standard deviation) of all accepted models in the results to show the range of working models.

2.5.4 Representing future drought scenarios

Projections of future climate change in California suggest that there will be shifts in precipitation frequency and variability during the dry season, with an increased number of dry days and increased evaporative demand, thus partly offsetting any increases in winter precipitation and possibly shifting towards more extreme events (Aghakouchak et al., 2018; Berg and Hall, 2015; Cook et al., 2015; Pierce et al., 2018). A rise in temperature is expected throughout the southwest and across the entire continent (Diffenbaugh et al., 2015). Furthermore, trends in emissions for California point towards a higher emissions scenario of RCP8.5, where annual maximum temperatures are projected to increase by more than 4 ∘C (Thorne et al., 2016). Such increasing temperature projections are anticipated to have important implications for evaporative demand and soil drying, especially in such arid grassland ecosystems of Southern California.

We used the SMBM model to explore the possible effects of such variations in P and ET0 on soil moisture and grassland vegetation in a simple parsimonious way, based on projections of shifting precipitation variability and evaporative demand (Berg and Hall, 2015; Pierce et al., 2018). In these explorations of specific types of climate change, we used monthly input data and did not alter other key parameters, such as soil properties and vegetation cover. The approach of only altering P or ET0 forcing of the SMBM allowed us to separately explore the influence of changes in precipitation and evaporative demand to moisture and plant water availability, under scenarios of more intense drought. The period 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2018 was used as a reference climate, and the experimental climate scenarios are represented as a deviation from it as follows:

-

Scenario A simulates the effects of a truncated rainy season (November–February) that reflects a loss of spring rains. This scenario represents an extreme decline in annual precipitation totals (average ∼30 % loss of annual P), the loss of precipitation in the shoulder seasons, and thus prolonged dry periods.

-

Scenario B simulates redistribution of lost spring rains from scenario A into the truncated rainy season from November–February, thus increasing the precipitation intensity and frequency during the compressed rainy season, combined with an increase in dry season length. Projections of CMIP5 indicated an increase in the number of dry days combined with increased frequencies of heavy precipitation, overall increasing interannual precipitation variability over California (Berg and Hall, 2015).

-

Scenario C simulates the effects of extreme drought. It uses scenario A's loss of spring rains, along with increased evaporative demand combined with a 25 % reduction in winter rainfall totals. Annual evaporative demand was increased to represent an average 4 ∘C increase in annual temperature, characterized by more warming in the dry season, which is based loosely on projected changes in temperature for Southern California and much of the southwest (Cook et al., 2015) under RCP8.5.

We retained dynamic vegetation responses in our investigation of the climate scenarios. To replace historic NDVI values (which do not exist for potential future scenarios), we developed a heuristic relationship between NDVI and available precipitation (aP) as aP = P–ET0, and we determined over what antecedent time period aP most strongly influences vegetation responses (1, 2, or 3 months), based on correlation strength (Pearson's correlation). We used a power law fit that best explained NDVI variation based on aP (using R2 and root-mean-square error (RMSE)), considering the non-drought, moderate, and extreme drought separately. We use this regression to create a synthetic NDVI input for our climate change simulations based on internally generated aP and to estimate kc based on Eq. (1).

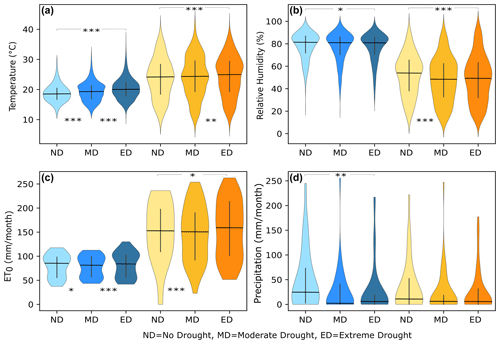

Figure 4Violin plots showing historic climate variables. (a) Monthly mean daytime temperature, (b) monthly mean relative humidity, (c) monthly cumulative reference evapotranspiration (ET0), and (d) cumulative monthly precipitation during the non-drought, moderate, and extreme drought for the coastal (blue hues) and inland (orange hues) sites. The vertical black line indicates the interquartile range and the black horizontal line the median. Statistical differences are indicated as p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (), and P<0.001 ().

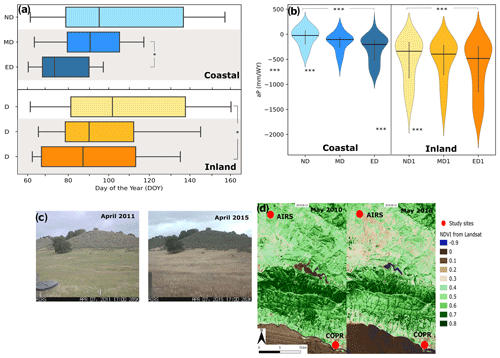

Figure 5(a) The onset of the dry season for the coastal (blue hues) and inland (orange hues) sites, presented as day of the year (DOY). Vertical black lines indicate the median DOY, and whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum DOY recorded. (b) Violin plots of available P for a water year (October and September) for the non-drought (ND), moderate (MD), and extreme drought (ED) periods. Black horizontal lines indicate median aP and vertical lines the interquartile range. (c) Webcam images of the inland site during non-drought (April 2011) and extreme drought (April 2015) highlight the early onset and decline of greenness at the height of the drought. (d) Decline in greenness throughout Santa Barbara County seen through NDVI images. Statistical significance is indicated as p<0.001 () and p<0.05 (*).

3.1 Climatology of the drought

The 2012–2019 drought in Southern California was marked by several years of above-average temperatures, high evaporative demand, and low precipitation. The seasonal temperature differences during the March–October dry season between drought periods were +0.7 ∘C between non-drought and moderate drought, +1.9 ∘C between non-drought and extreme drought, and +1.3 ∘C between moderate and extreme drought at the coastal site; the values were +1.1, +1.9, and +0.8 ∘C for the inland site, respectively. Daily maximum temperatures during March–October were on average 6.2 ∘C warmer at the inland site. Temperature differences were significantly different between all drought periods at both sites (Fig. 4a; Table S3). Due to the moderating effects of cooler and moister oceanic air and coastal fog, relative humidity at the coastal site averaged 81 % (Fig. 4b). Inland, the relative humidity was lower, averaging 54 % under non-drought conditions, and decreasing significantly during the extreme drought to an average of 48 %. The more moderate temperatures and high relative humidity at the coastal site were also reflected in a lower evaporative demand, resulting in ∼50 % lower annual ET0 compared to the inland site. Monthly ET0 averages at the coastal site were 265 and 515 mm yr−1 at the inland site during non-drought periods, with significant increases during the extreme drought period, especially at the inland site (Fig. 4c). Historical annual precipitation over the 11-year period was on average 20 % less at the inland site than at the coast, as the site lies in the rain shadow of the Santa Ynez mountain range. Precipitation averaged 147 mm yr−1 at the coastal site and 119 mm yr−1 at the inland site during the non-drought period, with precipitation at the coastal site showing a significant shift towards lower monthly totals during drought periods (Fig. 4d). The lowest October–September totals at both sites were recorded during the heart of the drought in 2014 with 170 mm yr−1 at the coastal and 162 mm yr−1 at the inland sites. A period of intense precipitation occurred from late 2016 to spring 2017, but the area remained in a state of severe drought until early 2019. A single dry year in 2018 temporarily increased the drought stress on the region again, before a very wet rainy season in 2019 finally relieved the pressure on ecosystems and water resources in Santa Barbara County locations and the entire state (Fig. 2b). Most notable was the emergence of a shift in the onset of the dry season, after which no more precipitation was recorded for three consecutive months or more until the start of the rainy season again in the fall (Fig. 5a). At the coastal site, we see that the shift of the onset of the dry season is most significant between non-drought and extreme drought, with a shift from DOY 95 to 73, which translates to a temporal shift roughly from early April to mid-March, whereas at the inland site the shift was already noticeable, with the DOY shifting from 103 (non-drought) via 90 (moderate drought) to 87 (extreme drought). This shift in early dry season onset from mid-April to late March triggered visible vegetation browning during the extreme drought by late March or early April at the inland site, as opposed to a more gradual browning between May and June in the years preceding the drought (Fig. 5c and d). The increased evaporative demand and reduced precipitation during the drought also resulted in significant changes to available P during drought periods, implying limited water availability for infiltration and soil moisture, especially inland (Fig. 5b).

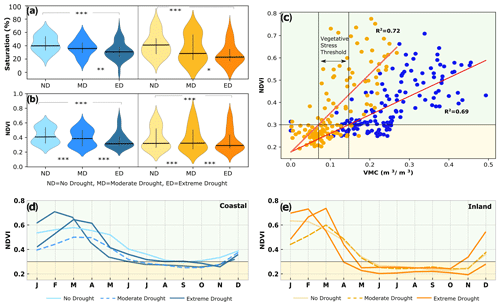

Figure 6(a) Monthly average saturation of soil moisture and (b) daily mid-month NDVI during non-drought, moderate, and extreme drought periods at the coastal (blue) and inland (orange) sites. Medians are indicated as black horizontal lines. Significance levels are indicated at p<0.001 (), 0.01 (), and 0.05 (*). (c) Regression of monthly average soil moisture and NDVI (R2=0.69 coastal, R2=0.72 inland) to establish a vegetative stress threshold, below which vegetation is most likely senescent. (d, e) Annual dynamics of NDVI during years of non-drought, moderate, and extreme drought years illustrate the shift in green-up (start of consistent NDVI increase following winter rains). Extreme drought (ED) years show maximum NDVI values early in the year, with a rapid decline in greenness thereafter.

3.2 Soil moisture and plant responses to drought

The drought was expressed differently in the soil moisture at each site. Soil moisture observations showed increased drying of soils during drought periods at both sites compared to the non-drought period, reaching extremely low moisture levels in 2013 and 2014 (daily saturation fell below 5 % inland). Similar low soil moisture occurred at both sites in 2008, a particularly dry year for the Santa Barbara (SB) region (Fig. 2b). At both sites, monthly average saturation was significantly different between the non-drought and drought periods at both sites, with significantly lower levels during the drought at both sites (Fig. 6a). Average saturation was similar at both sites during the non-drought period (40 %) but decreased to an average of 30 % at the coastal site and 23 % at the inland site during the extreme drought. At both sites average monthly NDVI during the non-drought period was significantly higher than during the drought periods (Fig. 6b). Monthly NDVI values over selected non-drought and drought years illustrate the strong seasonality of annual grass cover in the region, with a marked green-up period after the winter rains, followed by a decline into brown conditions over the dry season (Fig. 6d and e). In particular, there was a rapid increase of greenness during the extreme drought, following the winter rains in 2015 and 2016 and the subsequent unusually rapid and early decline of greenness in spring. Surprisingly, NDVI reached maximum values at the height of the drought in 2015 that were nearly double the non-drought averages (0.70 and 0.77 for coastal and inland, respectively). It is notable that the NDVI peak values during drought were higher than those for the non-drought period at both sites but very short-lived as NDVI declines rapidly back to low values, in contrast to the shoulder of greenness and slower decline of NDVI that occurred in most non-drought years. During the extreme drought, NDVI dropped rapidly below 0.3 in April at the inland site, which was also visible in webcam images and spatial NDVI imagery over the region (Figs. 5c and 6e). These differences in the seasonal variation of NDVI suggest a strategy of rapid grass green-up after winter rains, accelerated by mild winter temperatures during the drought and especially during the exceptionally warm winter in 2014–2015. The growth of additional vegetation under these conditions likely led to the observed rapid decline in moisture during spring, as vegetation quickly depleted any excess moisture, and subsequently experienced increased browning and senescence due to the early onset of the dry season (Fig. 5a). Correlation between NDVI and soil moisture of the concurrent month over our study period was strongly positive and statistically significant for both sites (R2=0.68 for coastal and inland, p<0.001), a relationship that was used to establish a heuristic vegetation stress threshold at VMC = 0.15 m3 m−3 for the coastal and VMC = 0.07 m3 m−3 for the inland site. We associated these thresholds with very low rates of photosynthetic activity, based on an NDVI threshold of 0.3 (Fig. 6c). Correlation between NDVI and aP over previous months revealed a 3-month lag in aP and NDVI at the coastal site (R2=0.82) and a 2-month lag at the inland site (R2=0.74). In order to develop a predictor (leading indicator) of vegetation response to aP, we fitted a linear regression model as follows:

where NDVIi denotes an estimated monthly NDVI, aPm is the amount of aP accumulated over a number of months m, and α and β are regression coefficients. A threshold of maximum NDVI was applied to both sites (0.75 for coastal and 0.7 for inland) during the regression analysis to account for the fact that NDVI saturates beyond a maximum amount of available water.

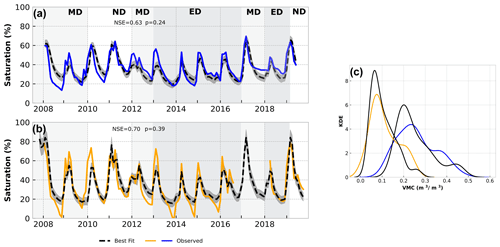

Figure 7SMBM results for the (a) coastal and (b) inland sites. Observed soil moisture is indicated by a solid line (blue coastal, orange inland), while simulated moisture is shown with a dashed black line. Grey shaded banding indicates ±1 SD (standard deviation) based on the output of 1000 Monte Carlo simulations. Grey vertical shading indicates non-drought (ND), moderate drought (MD), and extreme drought (ED) periods. (c) KDE curves of the observed and simulated moisture for the best model fit confirm the functionality of the model. NSE and p values from Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests are indicated in panels (a) and (b), indicating statistical similarity between observed and simulated values.

3.3 Soil moisture water balance model performance

Given the simple structure of the SMBM, we were encouraged that the best models at each site were effective at capturing and predicting the timing and magnitude of interactions between P, ET0, and soil moisture (Fig. 7a and b). Kernel density estimates (KDEs) for observed and simulated soil moisture distributions were statistically similar (Fig. 7c; KS = 0.12 and p=0.24 for coastal and KS = 0.12 and p=0.49 for inland) and simulated and modeled soil moisture showed good correlation (R2=0.84 for coastal and R2=0.84 for inland). However, we note that the best-fit simulated soil moisture at both sites may overestimate or underestimate observed VMC at particular points in the time series. Notably, the best model from the Monte Carlo simulations at the inland site was not able to capture the extreme dryness in 2013 and 2014. The SMBM assumes plant wilting point as the lowest level of soil moisture. However, in reality soil moisture may decline below wilting point during extremely dry periods through shallow soil evaporation. In such conditions, senescent or even dead plants can also act as a medium for the transference of water long after wilting has occurred, potentially compounding the effects of soil drying by evaporation (Briggs and Shantz, 1912). Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) coefficients showed good predictive abilities by the model (Fig. 7a and b).

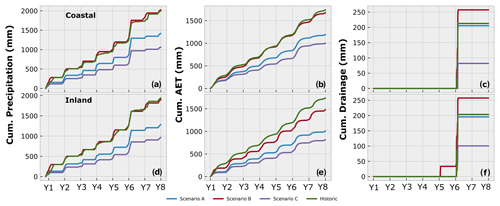

3.4 Soil moisture responses to plausible future drought scenarios

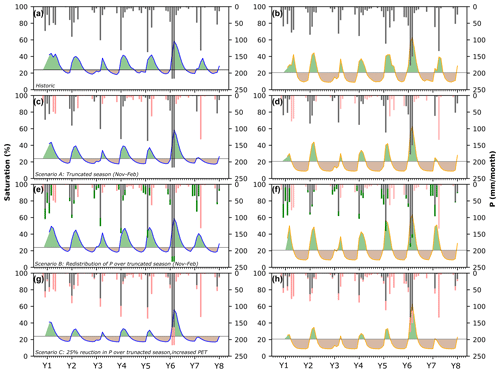

Under historic drought conditions, simulations for both coastal and inland sites reveal a clear seasonal pattern of time below the vegetative stress threshold in the fall, prior to winter rainfall, which by extension represents the senescent periods typical for grasslands in Southern California (Fig. 8a and b). The differences in the extent of time below the threshold as well as the minimum saturation levels are visible between sites and can be attributed to differences in soil water-holding capacity and aridity. Inland, soil saturation is below the appointed threshold for more than half (64 %) the simulation time compared to about 47 % at the coastal site. Scenarios A and C noticeably shift soil moisture towards a drier baseline, leading to more extended periods of low saturation and the accumulation of an extreme soil moisture deficit extending over several years (Fig. 8c, d, g and h). Under scenario C, for example, the time below the threshold would increase from the historical simulation by almost 50 % at the coastal site and only 25 % at the already dry inland site. This suggests that the previously buffered coastal locations would suffer disproportionally more from extended dry periods under extreme drought, as moisture reaches increasingly low levels previously unseen at this site. In contrast, the higher-intensity P over the shortened rainy season in scenario B actually reduces the amount of time below the stress threshold at the coastal site (by 2 % or 76 d over the 8-year simulation), and it only increases minimally by 2 % at the coastal site (Fig. 8e and f). In other words, redistributing the same annual P total into a briefer rainy season seems to mitigate the effects of no spring rains, and it also suggests a longer residence time of water in the soil (especially at the coastal site) that persists into the summer. This would allow plants to access soil moisture storage even after precipitation has stopped and likely support normal plant growth over the season, without any extensive drying. Under scenario B, the risk of extensive wildfires may also be less acute, as plants are not likely to suffer the level of intense and early senescence as would be seen in the other scenarios.

Figure 8Simulations of soil moisture for the coastal and inland site. Panels (a, b) show historic simulations. (c, d) Scenario A showing a truncated rainy season. Red bars indicate precipitation loss. (e, f) Scenario B showing a redistribution of annual P over the truncated season. Green bars indicate additional P, and red bars indicate P loss. (g, h) Scenario C showing a truncated season with additional 25 % loss of P and an increased evaporative demand equal to a +4 ∘C increase in mean annual temperature. The horizontal line indicates a vegetation stress threshold below which water becomes limiting for plants. Green shading indicates periods of greenness, while brown shading highlights periods of senescence.

The loss of spring rains, with precipitation limited between November–February, artificially extends the dry period to a total of 8 months of the year (Fig. 8c and d), resulting in a loss of ∼30 % of the annual precipitation in scenario A. Our simulations indicate that the loss of spring precipitation pulses in scenario A seems to have a larger effect on the inland site. While the overall water input is reduced at both sites due to the shortening of the season, the amount of water removed as AET only reduces minimally (<5 %) at the coastal site. However, at the inland site the loss of these events would result in the reduction of water used as AET by 10 %, suggesting that the spring precipitation is a more important component of the water balance for this site (Fig. 9b and e). The low moisture holding capacity due to sandy soils and the more arid climate at the inland site makes this site less resilient to the loss of spring precipitation at the time when plant development is about to start, and soil moisture is needed to support seed germination and biomass accumulation. Further analysis of the water balance suggests that the loss of spring rains seems to have only a minor effect on drainage (i.e., local potential groundwater recharge) at both sites, as drainage totals are only minimally reduced under scenario A compared to historic values (Fig. 9c and f). This suggests that precipitation events large enough to overcome antecedent soil moisture deficits and produce drainage only occur during the main winter months (November, December, January, February). Hence, any precipitation lost by the shortening of the season would not have contributed towards groundwater recharge.

Figure 9Cumulative water balance results for the coastal (a–c) and inland (d–f) sites. (a, d) Cumulative precipitation shows the changes in available water between different scenarios. (a, d) The proportion of available water used as AET varies among scenarios and shows a tight coupling of AET and P at the coastal site. (c, f) Drainage only occurs after reaching certain thresholds of monthly precipitation with the inland site benefitting from the added intensity in scenario B, which resulted in extra drainage in Y5.

Scenario B represents an exploration of climate projections that increase the intensity of winter rains in Southern California with no change in total wetness, expressed as an increased number of large daily P events, which increases the monthly totals during the shortened season (Fig. 8e and f). At the coastal site, the redistribution of precipitation seems to have little effect on the percentage of P removed by AET, suggesting a tight coupling of AET to precipitation at this site. At the inland site, however, the fraction of precipitation removed as AET declines by ∼10 % compared to the historical simulation (Fig. 9b and e). It appears that higher-intensity rain events at the inland site may be large enough to promote deep infiltration and local drainage below the evaporation zone (e.g., in Y5), due to the low water-holding capacity of the soils.

Rainfall event size and antecedent conditions together control drainage in our model, but our results indicate approximate rainfall thresholds that need to be overcome on daily and monthly timescales for drainage to occur. For example, a monthly total of >140 mm of precipitation at the inland site is the threshold above which drainage occurs. The events in Y6 both exceeded this threshold and produced considerable drainage for all simulations, with more than 50 % of the incoming precipitation in those months becoming drainage. In contrast, the coastal site requires more precipitation to produce drainage with a monthly threshold >230 mm, suggesting that much more of the annual rainfall is recycled to the atmosphere. On a daily timescale, drainage occurrence at the inland site corresponds to events of >20 mm d−1, which produce an additional drainage peak in Y5, while the coastal site requires several days of rainfall between 20–55 mm d−1 to produce drainage. Overall, it is evident that the increased precipitation intensity would contribute towards increasing the overall amount of drainage at both sites (Fig. 9c and f), with the added intensity increasing the potential for additional drainage and groundwater recharge at the inland site, despite the extended dry periods.

In the extreme drought conditions of scenario C, the effects of the increased precipitation loss and heightened ET0 affect several aspects of the water balance. The further reduction of precipitation over a shortened season has a major impact on soil moisture with increasing low levels of saturation at both sites. As less water would be available overall at both sites, cumulative drainage is reduced by >50 % compared to the historical simulation (Fig. 9c and f), and the loss of input precipitation by AET would be reduced at the inland site by up to 5 %, due to less water being available to be used by plants. Interestingly, at the coastal site AET exceeds input precipitation by ∼6 % over the simulation period, reflecting an overall drying of these coastal soils under extreme drought.

In light of the progression of climate change in semiarid environments such as Southern California, a better understanding of drought propagation and the climatic drivers of shifts in soil moisture and water availability to grassland vegetation (and, correspondingly, to the health and functioning of grassland ecosystems) would enable anticipation of how soil moisture and grassland dynamics might respond to intensified moisture limitations under future scenarios of climate change across the region. The severity of the recent synoptic California drought and its effects on vegetation were most notably documented through upland forest canopy water stress and mortality (Asner et al., 2016; Fettig et al., 2019; Goulden and Bales, 2019), as well as through declining groundwater levels that heavily impacted agricultural production throughout the Californian Central Valley (Thomas et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2017). Similarly, the intensified moisture loss and accelerated ET also impacted lowland vegetation in Southern California, including differential species responses within chaparral and grassland ecosystems (Breshears et al., 2005; Gremer et al., 2015; Okin et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2018). While the landscape in Southern California is dominated by vast stretches of brown grasslands during the dry season, the 2012–2019 drought hit Santa Barbara Country with considerable intensity and persistence, compared to the rest of the state (Fig. 2), and propagated into multiple years of soil moisture deficits and early die-off of grasses (Figs. 4–6).

Our analysis revealed that winter or spring precipitation deficits, coupled with higher evaporative demand in Southern California, led to temporal shifts in the onset of the dry season, which in turn also led to increased soil drying in spring and summer. The loss of essential precipitation pulses in spring months generated large soil moisture deficits and induced a faster die-off (browning) of grasses, especially at the inland site. We explored this shift in dry season onset further by simulating soil moisture responses under an even shorter rainy season. Our findings suggest that arid sites such as our inland site with low water-holding capacities, which is widespread over the region and more broadly over the southwest and other Mediterranean climate systems, would become increasingly vulnerable to climate change that favors milder winter and hotter summer temperatures, as well as decreased precipitation in key months during spring. Sites with low moisture holding capacities due to sandy soils and more arid climate seem less resilient to the loss of rain at the time when plant development is about to start and moisture is needed for seed germination and plant growth. Interestingly, the potential for apparent local groundwater recharge seems to remain unaffected by the loss of spring rains, suggesting that drainage only occurs during the winter months; even under prolonged periods of drought, there is a potential for local groundwater recharge. Such changes to the seasonal delivery of precipitation would increase the soil moisture drought frequency and magnitude, leading to much earlier senescence of vegetation and widespread desertification of the landscape while selectively priming the landscape for large and destructive wildfires, thus suggesting that already arid ecosystems might be brought to their physiological limit. These results can be viewed alongside prior work in the southwest that suggested chaparral landscapes (Okin et al., 2018) and perennial (C4) grasslands (Gremer et al., 2015) are increasingly prone to negative impacts from drought. Given how widespread the recent drought was in terms of spatial footprint and temporal length, more frequent occurrence of extreme drought conditions in the future could be devastating to perennial grasses and chaparral communities with larger consequences for entire grassland and shrubland ecosystems over a broad spatial extent (Gremer et al., 2015; Okin et al., 2018; Petrie et al., 2015).

With climate change projected to impact the temperate and precipitation regimes in California, as well as much of the southwestern US, the frequency and magnitude of droughts and drought-like conditions are expected to increase (Bradford et al., 2020; Diffenbaugh et al., 2015). Under a more severe emission scenario of RCP8.5, the frequency of extreme dry years is projected to almost triple with temperatures projected rise by up to 4 ∘C throughout California (Pierce et al., 2018; Thorne et al., 2016). Precipitation projections remain uncertain (Pierce et al., 2018, Bradford et al., 2020), but given the degree of already existing aridity in the southwest, even relatively modest changes to precipitation intensity and timing would create conditions much more conducive to prolonged drought periods. One climate scenario explored the combination of increased evaporative demand and decreased precipitation intensity and frequency, and the results highlighted the potential for multiyear soil moisture droughts to occur at even previously less affected coastal sites. Under such conditions, evaporative demand would exceed water availability, leaving coastal areas in a state of severe soil moisture deficit, thus putting a new strain on these ecologically sensitive areas and leave them potentially unsuitable as climate refugia and habitats for critical threatened and endangered species in the future.

Another key finding of the climate simulations has revealed that the occurrence of extreme events after prolonged periods of drought, as simulated in scenarios A and B, would provide temporary relief to soil moisture and most likely support considerable green-up and production of biomass during that season. However, if climate conditions revert to extreme dryness and minimal precipitation input during the following year, the soil moisture deficit would increase again to a level unlikely to support the extensive growth from the previous season. Under these conditions the senescent vegetation would turn into easily ignitable fuel that, coupled with the dried-out soils, would prime the landscape for extensive wildfires, thus potentially creating a severe chain reaction of extreme events as previously seen during the Montecito fires and mudslides.

The 2012–2019 drought in California had profound impacts on soil moisture and vegetation. Employing long-term monitoring data, we delineated the differential responses of soil moisture and vegetation dynamics of grassland ecosystems to this unprecedented, multiyear drought in Southern California. A temporal shift of dry season onset led to early senescence and browning of vegetation and rendered soil moisture resources prematurely exhausted, and the landscape was primed for easily ignitable and widespread wildfires. During the drought, temporal patterns of vegetation productivity changed, including increased greenness attributed to mild winter temperatures after prolonged dry periods. However, this new vegetation growth quickly reached a state of senescence due to the early onset of the dry season, exacerbating the soil moisture deficit.

Through a simple, parsimonious soil moisture water balance model, we further explored the moisture dynamics and water balance in terms of soil moisture for grasslands under different conditions that represent possible simplistic climate change scenarios. We linked soil moisture and vegetation response through NDVI and explored the effects of various changes to precipitation and evaporative demand. The results suggest that such changes could have unprecedented effects on soil moisture and water availability to grassland ecosystems, leading to rapid dieback and prolonged desiccation of the landscape. Our results highlighted the differential responses of moisture and vegetation over a small geographical area. In future, more extreme and prolonged droughts, characterized by a shorter rainy season, higher evaporative demand, and/or protracted dry periods, will likely lead to increased soil moisture deficits at sites with low water-holding capacities, as moisture levels are likely to drop to a level of elevated vegetative stress for much of the year. The combination of such climate-induced changes, loss of precipitation pulses in spring and summer, a continuing shift of early dry season onset, and increased evaporative demand are likely contributors to affect grassland ecosystems in future and drive even previously less affected coastal areas into more severe droughts, as well as induce widespread desertification of the landscape in semiarid environments. A shift to a drier moisture baseline of soils and vegetation could potentially have deleterious effects on species diversity, increase the risk of shrub encroachment and invasive species, and leave the region overall more prone to destructive and widespread wildfires.

Working code used for data analysis can be found under https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5031590 (mariaw-hub, 2021).

All climate and soil moisture data are publicly available for download at https://ideas.geog.ucsb.edu (last access: June 2021) (IDEAS, 2021).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-3713-2021-supplement.

Conceptualization of the research was done by MBS, MOC, KCa, DR and JS. Methodology was developed by MMW, MBS and MOC. Data curation and formal analysis was done by MMW and RS. The original draft was written by MMW. Review and editing was done by MMW, MBS, MOC, KC, JS, DR and RS.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (BCS-1660490, EAR-1700517 and EAR-1700555) and the Department of Defense's Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (RC18-1006). We thank Dar Roberts for providing the IDEAS data set, which is publicly available at http://www.geog.ucsb.edu/ideas/ (last access: 10 October 2019). Mark O. Cuthbert gratefully acknowledges funding for an Independent Research Fellowship from the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NE/P017819/1).

This research has been supported by the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (grant no. RC18-1006), the National Science Foundation (grant nos. BCS-1660490, EAR-1700517, and EAR-1700555), and the Natural Environment Research Council (grant no. NE/P017819/1).

This paper was edited by Nunzio Romano and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abatzoglou, J. T. and Williams, A. P.: Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 11770–11775, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607171113, 2016.

Aghakouchak, A., Ragno, E., and Love, C.: Projected Changes in Californias Precipitation Intensity-Duration-Frequency Curves, in: California's Fourth Climate Change Assessment, California Energy Commission, CA, USA, p. 32, 2018.

Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D., and Smith, M.: FAO Irrigation and Crop evapotranspiration (Guidelines for computing crop water requirements), Drainage Paper No. 56, available at: http://www.fao.org/3/x0490e/x0490e00.htm (last access: 1 April 2021), 1998.

Asner, G. P., Brodrick, P. G., Anderson, C. B., Vaughn, N., Knapp, D. E., and Martin, R. E.: Progressive forest canopy water loss during the 2012–2015 California drought, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, E249–E255, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523397113, 2016.

Ault, T. R., Mankin, J. S., Cook, B. I., and Smerdon, J. E.: Relative impacts of mitigation, temperature, and precipitation on 21st-century megadrought risk in the American Southwest, Sci. Adv., 2, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1600873, 2016.

Berg, N. and Hall, A.: Increased interannual precipitation extremes over California under climate change, J. Climate, 28, 6324–6334, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00624.1, 2015.

Berg, N. and Hall, A.: Anthropogenic warming impacts on California snowpack during drought, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 2511–2518, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL072104, 2017.

Bradford, J. B., Schlaepfer, D. R., Lauenroth, W. K., and Palmquist, K. A.: Robust ecological drought projections for drylands in the 21st century, Global Change Biol., 23, 3906–3919, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15075, 2020.

Breshears, D. D., Cobb, N. S., Rich, P. M., Price, K. P., Allen, C. D., Balice, R. G., Romme, W. H., Kastens, J. H., Floyd, M. L., Belnap, J., Anderson, J. J., Myers, O. B., and Meyer, C. W.: Regional vegetation die-off in response to global-change-type drought, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 15144–15148, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0505734102, 2005.

Briggs, L. J. and Shantz, H. L.: The Wilting Coefficient and Its Indirect Determination, Bot. Gaz., 53, 20–37, 1912.

Caylor, K. K., D'Odorico, P., and Rodriguez-Iturbe, I.: On the ecohydrology of structurally heterogeneous semiarid landscapes, Water Resour. Res., 42, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005WR004683, 2006.

Caylor, K. K., Scanlon, T. M., and Rodriguez-Iturbe, I.: Ecohydrological optimization of pattern and processes in water-limited ecosystems: A trade-off-based hypothesis, Water Resour. Res., 45, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR007230, 2009.

Coates, A. R., Dennison, P. E., Roberts, D. A., and Roth, K. L.: Monitoring the impacts of severe drought on southern California Chaparral species using hyperspectral and thermal infrared imagery, Remote Sens., 7, 14276–14291, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs71114276, 2015.

Cook, B. I., Ault, T. R., and Smerdon, J. E.: Unprecedented 21st century drought risks in the American south west and central plains, Sci. Adv., 1, e1400081, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1400082, 2015.

Cuthbert, M. O., MacKay, R., and Nimmo, J. R.: Linking soil moisture balance and source-responsive models to estimate diffuse and preferential components of groundwater recharge, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 17, 1003—1019, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-1003-2013, 2013.

Cuthbert, M. O., Taylor, R. G., Favreau, G., Todd, M. C., Shamsudduha, M., Villholth, K. G., MacDonald, A. M., Scanlon, B. R., Kotchoni, D. O. V., Vouillamoz, J. M., Lawson, F. M. A., Adjomayi, P. A., Kashaigili, J., Seddon, D., Sorensen, J. P. R., Ebrahim, G. Y., Owor, M., Nyenje, P. M., Nazoumou, Y., Goni, I., Ousmane, B. I., Sibanda, T., Ascott, M. J., Macdonald, D. M. J., Agyekum, W., Koussoubé, Y., Wanke, H., Kim, H., Wada, Y., Lo, M. H., Oki, T., and Kukuric, N.: Observed controls on resilience of groundwater to climate variability in sub-Saharan Africa, Nature, 572, 230–234, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1441-7, 2019.

Diffenbaugh, N. S., Swain, D. L., and Touma, D.: Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 112, 3931–3936, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1422385112, 2015.

D'Odorico, P., Caylor, K., Okin, G. S., and Scanlon, T. M.: On soil moisture-vegetation feedbacks and their possible effects on the dynamics of dryland ecosystems, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 112, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JG000379, 2007.

Dong, C., MacDonald, G. M., Willis, K., Gillespie, T. W., Okin, G. S., and Williams, A. P.: Vegetation Responses to 2012–2016 Drought in Northern and Southern California, Geophys. Res. Lett., 3810–3821, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL082137, 2019.

Evans, C. M., Dritschel, D. G., and Singer, M. B.: Modeling Subsurface Hydrology in Floodplains, Water Resour. Res., 54, 1428–1459, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017WR020827, 2018.

Fettig, C. J., Mortenson, L. A., Bulaon, B. M., and Foulk, P. B.: Tree mortality following drought in the central and southern Sierra Nevada, California, U.S., Forest. Ecol. Manage., 432, 164–178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.09.006, 2019.

Gillespie, T. W., Ostermann-kelm, S., Dong, C., Willis, K. S., Okin, G. S., and Macdonald, G. M.: Monitoring changes of NDVI in protected areas of southern California, Ecol. Indic., 88, 485–494, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.01.031, 2018.

Glenn, E. P., Neale, C. M. U., Hunsaker, D. J., and Nagler, P. L.: Vegetation index-based crop coefficients to estimate evapotranspiration by remote sensing in agricultural and natural ecosystems, Hydrol. Process., 25, 4050–4062, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.8392, 2011.

Goulden, M. L. and Bales, R. C.: California forest die-off linked to multi-year deep soil drying in 2012–2015 drought, Nat. Geosci., 12, 632–637, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0388-5, 2019.

Gremer, J. R., Bradford, J. B., Munson, S. M., and Duniway, M. C.: Desert grassland responses to climate and soil moisture suggest divergent vulnerabilities across the southwestern United States, Global Change Biol., 21, 4049–4062, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13043, 2015.

Gu, Y., Hunt, E., Wardlow, B., Basara, J. B., Brown, J. F., and Verdin, J. P.: Evaluation of MODIS NDVI and NDWI for vegetation drought monitoring using Oklahoma Mesonet soil moisture data, Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL035772, 2008.

Hunsaker, D. J., Pinter, P. J., and Kimball, B. A.: Wheat basal crop coefficients determined by normalized difference vegetation index, Irrig. Sci., 24, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00271-005-0001-0, 2005.

IDEAS: IDEAS Home Page, available at: https://ideas.geog.ucsb.edu, last access: June 2021.

Keeley, J. E. and Syphard, A. D.: Climate change and future fire regimes: Examples from California, Geoscience, 6, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences6030037, 2016.

Lian, X., Piao, S., Li, L. Z. X., Li, Y., Huntingford, C., Ciais, P., Cescatti, A., Janssens, I. A., Peñuelas, J., Buermann, W., Chen, A., Li, X., Myneni, R. B., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Yang, Y., Zeng, Z., Zhang, Y., and McVicar, T. R.: Summer soil drying exacerbated by earlier spring greening of northern vegetation, Sci. Adv., 6, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax0255, 2020.

Liu, S., Roberts, D. A., Chadwick, O. A., and Still, C. J.: Spectral responses to plant available soil moisture in a Californian Grassland, Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf., 19, 31–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2012.04.008, 2012.

Ludwig, J. A., Wilcox, B. P., Breshears, D. D., Tongway, D. J., and Imeson, A. C.: Vegetation patches and runoff-erosion as interacting ecohydrological processes in semiarid landscapes, Ecology, 86, 288–297, https://doi.org/10.1890/03-0569, 2005.

mariaw-hub: mariaw-hub/SMBM: SMBM (Version v1.0), Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5031590, 2021.

McDowell, N., Pockman, W. T., Allen, C. D., Breshears, D. D., Cobb, N., Kolb, T., Plaut, J., Sperry, J., West, A., Williams, D. G., and Yepez, E. A.: Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: Why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought?, New Phytol., 178, 719–739, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02436.x, 2008.

Michaelides, K., Lister, D., Wainwright, J., and Parsons, A. J.: Vegetation controls on small-scale runoff and erosion dynamics in a degrading dryland environment, Hydrol. Process., 23, 1617–1630, 2009.

Nagler, P. L., Cleverly, J., Glenn, E., Lampkin, D., Huete, A., and Wan, Z.: Predicting riparian evapotranspiration from MODIS vegetation indices and meteorological data, Remote Sens. Environ., 94, 17–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2004.08.009, 2005.

NDMC: United States Drought Monitor, United States Drought Monit, available at: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/ (last access: 12 February 2021), 2020.

Oakley, N. S., Cannon, F., Munroe, R., Lancaster, J. T., Gomberg, D., and Martin Ralph, F.: Brief communication: Meteorological and climatological conditions associated with the 9 January 2018 post-fire debris flows in Montecito and Carpinteria, California, USA, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 18, 3037–3043, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-18-3037-2018, 2018.

Okin, G. S., Dong, C., Willis, K. S., Gillespie, T. W., and MacDonald, G. M.: The Impact of Drought on Native Southern California Vegetation: Remote Sensing Analysis Using MODIS-Derived Time Series, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 123, 1927–1939, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JG004485, 2018.

Petrie, M. D., Collins, S. L., and Litvak, M. E.: The ecological role of small rainfall events in a desert grassland, Ecohydrology, 8, 1614–1622, https://doi.org/10.1002/eco.1614, 2015.

Pierce, D. W., Kalansky, J. F., and Cayan, D. R.: Climate, Drought, and Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the Fourth California Climate Assessment, in: California's Fourth Climate Change Assessment, California Energy Commission, available at: https://www.climateassessment.ca.gov/ (last access: 10 August 2020), 2018.

Prugh, L. R., Deguines, N., Grinath, J. B., Suding, K. N., Bean, W. T., Stafford, R., and Brashares, J. S.: Ecological winners and losers of extreme drought in California, Nat. Clim. Change, 8, 819–824, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0255-1, 2018.

Quichimbo, E. A., Singer, M. B., and Cuthbert, M. O.: Characterizing groundwater-surface water interactions in idealized ephemeral stream systems, Hydrol. Process., https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.13847, in press, 2020.

Roberts, D., Bradley, E., Roth, K., Eckmann, T., and Still, C.: Linking physical geography education and research through the development of an environmental sensing network and project-based learning, J. Geosci. Educ., 58, 262–274, https://doi.org/10.5408/1.3559887, 2010.

Shukla, S., Safeeq, M., Aghakouchak, A., Guan, K., and Funk, C.: Temperature impacts on the water year 2014 drought in California, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, 4384–4393, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL063666, 2015.

Singer, M. B. and Michaelides, K.: Deciphering the expression of climate change within the Lower Colorado River basin by stochastic simulation of convective rainfall, Environ. Res. Lett., 12, 104011, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8e50, 2017.

Singer, M. B., Michaelides, K., and Hobley, D. E. J.: STORM 1.0: A simple, flexible, and parsimonious stochastic rainfall generator for simulating climate and climate change, Geosci. Model Dev., 11, 3713–3726, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-3713-2018, 2018.

Singh, M. and Meyer, W. M.: Plant-soil feedback effects on germination and growth of native and non-native species common across Southern California, Diversity, 12, 217, https://doi.org/10.3390/D12060217, 2020.

Small, E. E., Roesler, C. J., and Larson, K. M.: Vegetation response to the 2012–2014 California drought from GPS and optical measurements, Remote Sens., 10, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10040630, 2018.

Swain, D. L., Tsiang, M., Haugen, M., Singh, D., Charland, A., Rajaratnam, B., and Diffenbaugh, N. S.: The Extraordinary California Drought of 2013/2014: Character, Context, And The Role Of Climate Change, Am. Meteorol. Soc., USA, 2014.

Thomas, B. F., Famiglietti, J. S., Landerer, F. W., Wiese, D. N., Molotch, N. P., and Argus, D. F.: GRACE Groundwater Drought Index: Evaluation of California Central Valley groundwater drought, Remote Sens. Environ., 198, 384–392, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.06.026, 2017.

Thorne, J. H., Boynton, R. M., Holguin, A. J., Stewart, J. A., and Bjorkman, J.: A climate change vulnerability assessment of California's terrestrial vegetation, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, University of California, Davis, USA, 2016.

Trenberth, K. E.: Changes in precipitation with climate change, Clim. Res., 47, 123–138, https://doi.org/10.3354/cr00953, 2011.

Westra, S., Fowler, H. J., Evans, J. P., Alexander, L. V., Berg, P., Johnson, F., Kendon, E. J., Lenderink, G., and Roberts, N. M.: Future changes to the intensity and frequency of short-duration extreme rainfall, Rev. Geophys., 52, 522–555, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014RG000464, 2014.

Wilkening, J., Pearson-Prestera, W., Mungi, N. A., and Bhattacharyya, S.: Endangered species management and climate change: When habitat conservation becomes a moving target, Wildl. Soc. Bull., 43, 11–20, https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.944, 2019.

Williams, A. P., Seager, R., Abatzoglou, J. T., Cook, B. I., Smerdon, J. E., and Cook, E. R.: Contribution of anthropogenic warming to California drought during 2012–2014, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, 6819–6828, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL064924, 2015.

Williams, A. P., Abatzoglou, J. T., Gershunov, A., Guzman-Morales, J., Bishop, D. A., Balch, J. K., and Lettenmaier, D. P.: Observed Impacts of Anthropogenic Climate Change on Wildfire in California, Earth's Future, 7, 892–910, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EF001210, 2019.

Wilson, S. D., Schlaepfer, D. R., Bradford, J. B., Lauenroth, W. K., Duniway, M. C., Hall, S. A., Jamiyansharav, K., Jia, G., Lkhagva, A., Munson, S. M., Pyke, D. A., and Tietjen, B.: Functional Group, Biomass, and Climate Change Effects on Ecological Drought in Semiarid Grasslands, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 123, 1072–1085, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JG004173, 2018.

Xiao, M., Koppa, A., Mekonnen, Z., Pagán, B. R., Zhan, S., Cao, Q., Aierken, A., Lee, H., and Lettenmaier, D. P.: How much groundwater did California's Central Valley lose during the 2012–2016 drought?, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 4872–4879, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073333, 2017.