the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Isotopic variations in surface waters and groundwaters of an extremely arid basin and their responses to climate change

Yu Zhang

Hongbing Tan

Peixin Cong

Dongping Shi

Wenbo Rao

Xiying Zhang

Climate change accelerates the global water cycle. However, the relationships between climate change and hydrological processes in the alpine arid regions remain elusive. We sampled surface water and groundwater at high spatial and temporal resolutions to investigate these relationships in the Qaidam Basin, an extremely arid area in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Stable H–O isotopes and radioactive 3H isotopes were combined with atmospheric simulations to examine hydrological processes and their response mechanisms to climate change. Contemporary climate processes and change dominate the spatial and temporal variations of surface water isotopes, specifically the westerlies moisture transport and the local temperature and precipitation regimes. The H–O isotopic compositions in the eastern Kunlun Mountains showed a gradually depleted eastward pattern, while a reverse pattern occurred in the Qilian Mountains water system. Precipitation contributed significantly more to river discharge in the eastern basin (approximately 45 %) than in the middle and western basins (10 %–15 %). Moreover, increasing precipitation and a shrinking cryosphere caused by current climate change have accelerated basin groundwater circulation. In the eastern and southwestern Qaidam Basin, precipitation and meltwater infiltrate along preferential flow paths, such as faults, volcanic channels, and fissures, permitting rapid seasonal groundwater recharge and enhanced terrestrial water storage. However, compensating for water loss due to long-term ice and snow melt will be a challenge under projected increasing precipitation in the southwestern Qaidam Basin, and the total water storage may show a trend of increasing before decreasing. Great uncertainty about water is a potential climate change risk facing the arid Qaidam Basin.

- Article

(12793 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(611 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

In the face of ongoing environmental changes, a thorough understanding of the hydrological cycle is a prerequisite for accurate trend forecasting and helps to design efficient water resource management strategies. Over the past half century, climate change and more intense human activities have led to global water cycle acceleration and water resource redistribution at different scales (Huntington et al., 2006; Durack et al., 2012; Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021). For example, rapid warming has sharply expanded lakes in the Tibetan Plateau and shrunk them in the Mongolian Plateau (Zhang et al., 2017) and has also exacerbated the severe irrigation water shortage in parts of southern Asia and eastern Asia (Haddeland et al., 2014). Moreover, warming is expected to reduce groundwater storage in the western United States (Condon et al., 2020). Currently, the climate in arid regions of northwestern China is changing from warm–dry to warm–wet (Zhang et al., 2021). The resulting uncertainties in water resources in arid alpine basins pose new challenges to understand the hydrological cycle and water resources. These key scientific issues can be addressed by investigating the spatial and temporal distribution and control mechanisms of surface water and groundwater resources within the basin under accelerating climate change.

The Tibetan Plateau, known as the Third Pole, has complex cryospheric–hydrologic–geodynamic processes and is especially vulnerable to global warming (Zhang et al., 2017; Yao et al., 2022). The Qaidam Basin in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau is the area that has warmed the most in the entire Tibetan Plateau (Li et al., 2015; Kuang and Jiao, 2016; Yao et al., 2022). Since 1961, the average temperature of the basin has increased at an alarming rate of 0.53 ∘C per decade (Wang et al., 2014), resulting in increased precipitation and cryospheric retreat (Song et al., 2014; Xiang et al., 2016; Zou et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023). These changes have led to drastic spatial changes in surface water and groundwater storage; increasing runoff over wide areas (Jiao et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2021); and hydrological changes in the central and northern basin, such as the lakes expansion (Ke et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). However, several questions remain to be answered: how are hydrological changes in the basin driven by climate change? What are the potential influences of these changes on the water resources of the basin? The dynamics of surface water and groundwater, which link precipitation and meltwater from high elevations with the low-lying lake basins, provide evidence of the effects of climate change on water cycle processes. The Qaidam Basin is therefore an excellent site to reveal the mechanisms of global-warming-induced responses to the hydrological cycle on the Tibetan Plateau.

The isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen are useful tracers for the water cycle and climate reconstruction. They can help elucidate the processes that control water cycle changes, thus providing scientific evidence for human adaptations and effects on future global changes (Craig, 1961; Dansgaard, 1964; Yao et al., 2013; Bowen et al., 2019; Kong et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2023). Water isotope records provide key information on water flow, and they can compensate for the paucity of hydrometeorological, geological, and borehole data in hydrological research. Stable H–O isotopes and radioactive 3H isotopes have been widely applied to quantify surface water or groundwater recharge sources, interactions, budgets, and ages (Befus et al., 2017; Stewart et al., 2017; Moran et al., 2019; Bam et al., 2020; Rodriguez et al.,2021; Shi et al., 2021; Ahmed et al., 2022; Benettin et al., 2022). Previous researchers have also performed a substantial amount of work on using isotopes to delineate the water cycle in the Qaidam Basin (Xu et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2017, 2018; Zhao et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2021; Yang and Wang, 2020; Yang et al., 2021). These studies have enhanced our understanding of aquifer properties in local regions and recharge mechanisms. However, past assessments of the water cycle in the Qaidam Basin have been constrained by the challenges of the harsh natural conditions and scarce hydrogeological data. It is a great challenge to achieve a comprehensive elucidation of the basin-scale water cycle mechanism. Furthermore, seasonal recharge of the whole basin has not been systematically explored. Various hydrological, climatic, and hydrogeological conditions of the basin are caused by continuous changes in the topographical and tectonic spatial patterns; moreover, the hydrological effects exerted by anthropogenic climate change differ seasonally (Jasechko et al., 2014). Therefore, it is urgent to develop a comprehensive understanding of the basin water cycle and its seasonal changes. While carrying out a comprehensive assessment of differences in isotopic compositions of various potential recharge sources, it is fundamental to use the same technical methods for the systematic sampling and isotopic characterization of the basin.

In this study, we constrain the hydrological cycle of the Qaidam Basin and surrounding mountains using stable H–O and radioactive 3H isotope data collected during the wet and dry seasons from eight study sites in major watersheds in the basin. The study aims are (1) to elucidate the distribution pattern of surface water and groundwater isotopes in this alpine arid basin at various spatial and seasonal scales; (2) to identify and quantify the main components of the regional water cycle, their timing and spatial heterogeneity; and (3) to reveal isotopic hydrological responses to climate change and to predict the trend of the changes of Qaidam Basin water resources.

2.1 General features

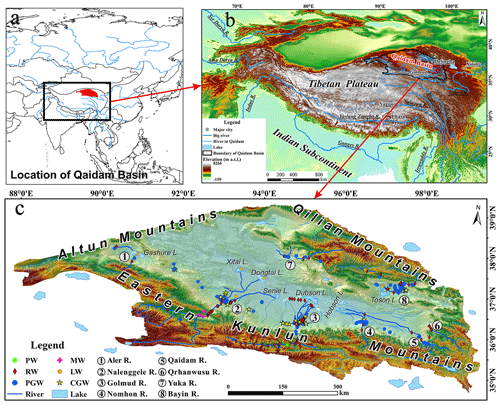

The Qaidam Basin is a closed fault depression basin in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau surrounded by the Kunlun, Qilian and Altun mountains (Fig. 1a, b). The basin is one of the four main basins in China with an area of approximately 250 000 km2. It has a plateau continental climate with a typical alpine arid inland basin characterized by drought. There are significant temperature variations across the basin, and the mean annual temperature is less than 5 ∘C. Annual precipitation varies from 200 mm in the southeastern region to 15 mm in the northwestern region. Mean annual relative humidity is 30 %–40 %, with a minimum of less than 5 %. Modern glaciers have formed in the mountains on the western, southern and northeastern sides of the basin. The basin is surrounded by more than 100 rivers, about 10 rivers of which are perennial, with most of the local rivers being intermittent river systems. The rivers are mainly distributed on the eastern side of the basin but are scarce on the western side. The water in the basin's lakes is predominantly saline, with a total of 31 salt lakes.

2.2 Basic hydrogeological setting

The basin basement consists of Precambrian crystalline metamorphic rock series, and the caprock is of Paleogene–Neogene and Quaternary strata. The mountainous area surrounding the basin is dominated by a Paleogene system, and the basin area and basin boundary zone are characterized by a wide distribution of the Paleogene–Neogene system. The Quaternary system is mainly distributed in the central basin region and the intermountain valley region. The basin terrain is slightly tilted from the northwest to southeast, and the height gradually reduces from 3000 m to approximately 2600 m. The distribution of the basin landforms shows a concentric ring shape. From the rim to the center, the distributions of the diluvial gravel fan (Gobi), alluvial–diluvial silt plain, lacustrine–alluvial silt clay plain and lacustrine silt–salt plains follow a regular pattern. Salt lakes are extensively distributed in the lowlands. The inner edge of the Gobi belt in the northwestern basin region is clustered with hills that are less than 100 m in height. The southeastern region of the basin has pronounced subsidence, and the alluvial and lacustrine plains are extensive. In the northeastern basin, a secondary small intermountain basin has been formed between the basin and the Qilian Mountains by the uplifting of a series of low mountain fault blocks of metamorphic rock series.

The Qaidam Basin is located in the Qin-Qi-Kun tectonic system, where there is strong neotectonic movement, and a series of syncline–anticline tectonic belts and regional deep faults have formed around it. The fault structures in the Qaidam Basin are very well developed and include the northeasterly Altun fault in the north, the northwesterly Saishenteng–Aimunik northern margin deep fault in the northeast, the westerly Qaidam northern margin deep fault in the northwest, the Qimantag Mountains and Burhan Budai Mountains–Aimunik northern margin deep fault in the south, and the northwesterly Sanhu major fault and northeasterly Qigaisu–Dongku fault in the central basin region.

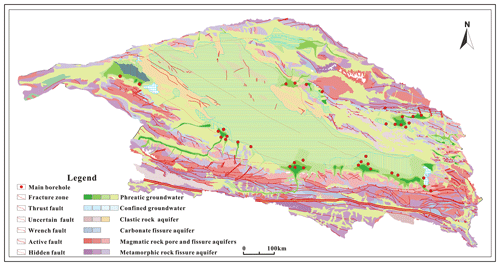

Figure 2Hydrogeologic map of the Qaidam Basin (modified from Xi'an Center, China Geological Survey, http://www.xian.cgs.gov.cn/, last access: 21 June 2023). The color of different patches of the same aquifer, from dark to light, denotes high to low in water yield property.

The distribution of surface water in the basin is constrained by topography and neotectonic movements and appears to have a general centripetal radial pattern (Fig. 1c). There is widespread surface water and groundwater exchange. The mountainous areas are rich in precipitation and ice or snow meltwater and are the main runoff-producing areas. Runoff from the mountains flows through the Gobi belt, where most of it infiltrates into the groundwater system. Groundwater discharges to the surface from springs in confined aquifers or springs at the front edge of the alluvial fan. This water finally flows into terminal lakes.

Groundwater can be roughly classified as (i) fractured-bedrock water, (ii) leached pore water and local confined groundwater, (iii) phreatic groundwater and confined artesian water, (iv) saline phreatic groundwater, and (v) brine and saline confined artesian water. Surface water and groundwater salinity and solutes are gradually enriched along the flow path (Fig. 2; Wang et al., 2008).

3.1 Sampling and analysis

We collected samples from eight major river–groundwater systems in the region from 2019 to 2021. We collected samples from six of the systems once a hydrological year, consisting of the wet season (July–August) and the dry season (March–April). Precipitation and snow meltwater were collected from the eastern Kunlun Mountains. Snow meltwater was collected in the dry season, whereas precipitation was collected at several times during a hydrological year. In total, 239 sampling points were established: phreatic groundwater (n=100), confined groundwater (n=43), spring water (n=6), river water (n=81), lake water (n=5), snow meltwater (n=3) and precipitation (n=1). A total of 422 sets of samples were collected. No sampling point was established in the northwestern basin because the southern slope and front edge of the Altun Mountains consisted of Tertiary system halite sedimentation and Quaternary system thick salt flats, and no freshwater body was developed. Therefore, the sample collection covers the entire Qaidam Basin and each of the major endorheic regions.

Hydrogen and oxygen isotopes (2H, 3H and 18O) were analyzed at the State Key Laboratory of Hydrology-Water Resources and Hydraulic Engineering, Hohai University, China. A MAT253 mass spectrometer was used to measure the ratios of 2H 1H and 18O 16O, and the results were compared with the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), expressed in δ (‰), with the analytical precision (1σ) of the instrument for these isotopes being lower than ±1 ‰ and ±0.1 ‰. To determine the tritium (3H) concentration, the water sample was first concentrated by electrolysis. Following sample enrichment, measurements were carried out using low background liquid scintillation counting (TRI-CARB 3170 TR/SL). The findings were expressed in terms of absolute concentration in tritium units (TU), the detection limit of the instrument was 0.2 TU, and the precision was improved to less than ±0.8 TU.

3.2 Hydrograph separation

In the analysis of water sources among hydrological processes, endmember mixing models are widely used. The contribution of each recharge endmember to the mixed water body was estimated with a Bayesian mixing model that considers to the heterogeneity of different endmember isotopes and/or water chemistry parameters (Hooper et al., 1990; Hooper, 2003; Chang et al., 2018). The process is as follows:

where fi represents the proportion of water source i,n represents the number of endmembers, and and represent the level of tracer j in mixed component and endmember i, respectively.

The Bayesian mixing models (MixSIAR) coded in R can quantify the contributions of more than two potential endmembers (Parnell et al., 2010). In this study, based on the differences in the water body properties and isotopic composition of each endmember, δ18O, δD and d-excess (d-excess =δD − 8 δ18O) data were used as parameters in the modeling. The model was calculated at a fractional increment of 1 % and an uncertainty level of 0.1 %.

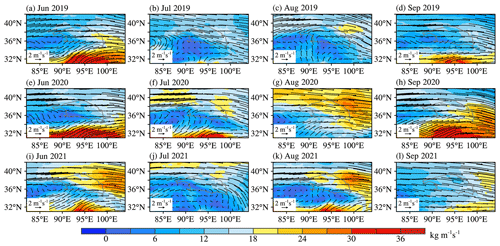

3.3 Water vapor trajectory

The source and transport route of moisture can be monitored based on the water vapor flux field derived from the monthly mean ERA5 reanalysis data () of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF, https://www.ecmwf.int/, last access: 1 June 2022) (Hersbach et al., 2019). After taking into account that more than 70 % of the precipitation in the Qaidam Basin occurs from June to September, the monthly mean ERA5 reanalysis data in this period from 2019 to 2021 were used to analyze the water vapor transport path in and around the study area. Based on the average altitude of >3000 m at the study site, the simulated atmospheric pressure was set to 500 hPa. The majority of the atmospheric water vapor was distributed in the range of 0–2 km above ground, and the simulated height did not have any significant influence on the findings (Li and Garzione, 2017; Yang and Wang, 2020).

4.1 Spatial and seasonal characteristics of surface water δ18O–δD

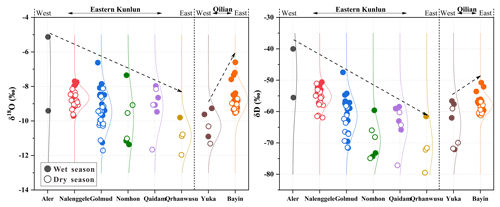

In the Qaidam Basin, considerable spatial and seasonal variations exist in the stable H–O isotopes of surface water (Fig. 3). The isotopic compositions of rivers originating from the eastern Kunlun Mountains contrast with those from Qilian Mountains, where the heavy isotopes of the eastern Kunlun Mountains are gradually depleted in the direction of west to east, and the reverse holds true for the Qilian Mountains. Of these, the δ18O and δD values are significantly positive in the southwestern basin, while they are significantly negative in the eastern basin. Apart from the Nomhon River, all watersheds exhibit a characteristic seasonal variation of being enriched in heavy isotopes during the wet season relative to the dry season. The mean δ18O and δD values in surface water are more positive by −0.08 ‰ to 1.08 ‰ and 0.6 ‰ to 10.6 ‰, respectively, in the wet season. Moreover, the seasonal variations of δ18O and δD are more evident in the downstream river compared to the upstream. For instance, the δ18O value of the downstream Nomhon River is 3.66 ‰ higher during the wet season compared to the dry season. These phenomena reflect the differences in the recharge sources of the river during both the wet and dry seasons and the strong evaporation effect in the central basin region.

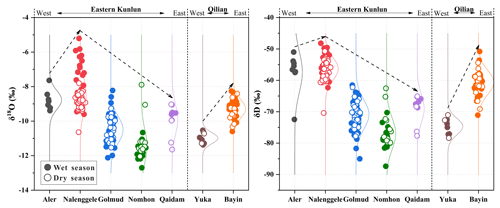

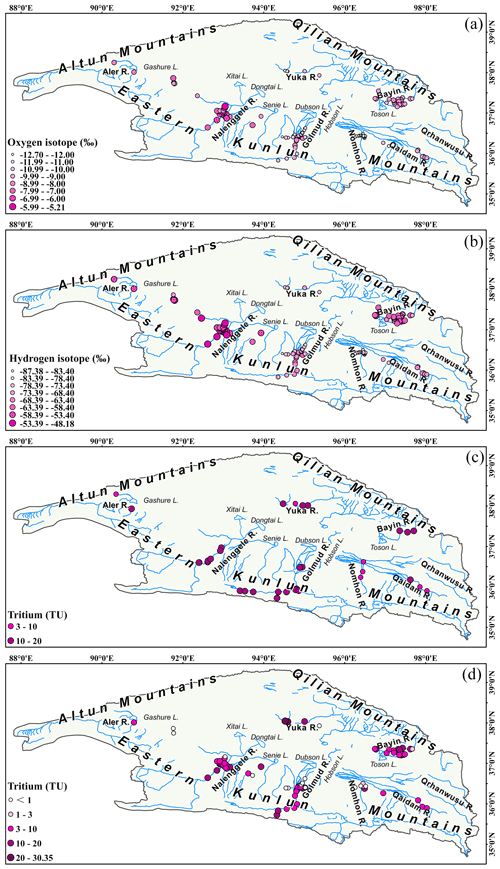

4.2 Spatial and seasonal characteristics of groundwater δ18O–δD

The spatial variability of groundwater stable H–O isotopes is more pronounced compared with river water, although it appears to follow the same distribution pattern as river water in the basin (Fig. 4). The δ18O and δD values in the groundwater system are lower, and seasonal fluctuations were smaller compared to those in surface water because the kinetic fractionation of isotopes caused by evaporation and mixing are weaker in groundwater than in surface water. Specifically, the average seasonal variation of δ18O in each of the groundwater systems ranges from −0.75 ‰ to +0.84 ‰, and the largest seasonal variations in individual boreholes are +3.31 ‰ and −3.16 ‰, respectively. This suggests that the groundwater reflects a spatial and temporal average of the surface water isotopic signal, and averaging reduces the variability of the values. The region with the greatest seasonal fluctuations of groundwater is located in the Nalenggele River (southwestern basin), and the groundwater δ18O and δD in the wet season are noticeably more positive compared to those in dry season. This indicates that groundwater flow is rapid, and each season, new infiltration displaces the earlier infiltration. The adjacent Golmud River, however, has the least seasonal variations in δ18O and δD. In contrast, this suggests that flow is slow. Although there are no obvious differences in the topography and landforms between the two adjacent watersheds, significant differences are observed in the isotope signatures of the two, where both surface water and groundwater show much more positive δ18O and δD values in the Nalenggele River than in the Golmud River catchment.

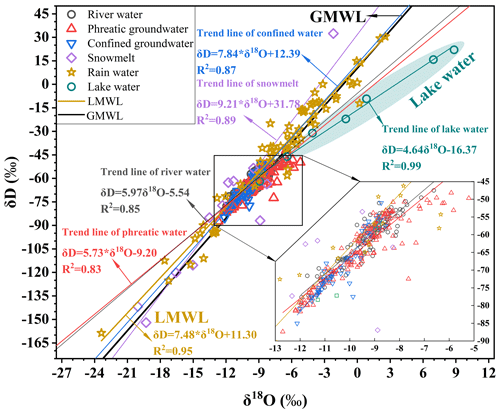

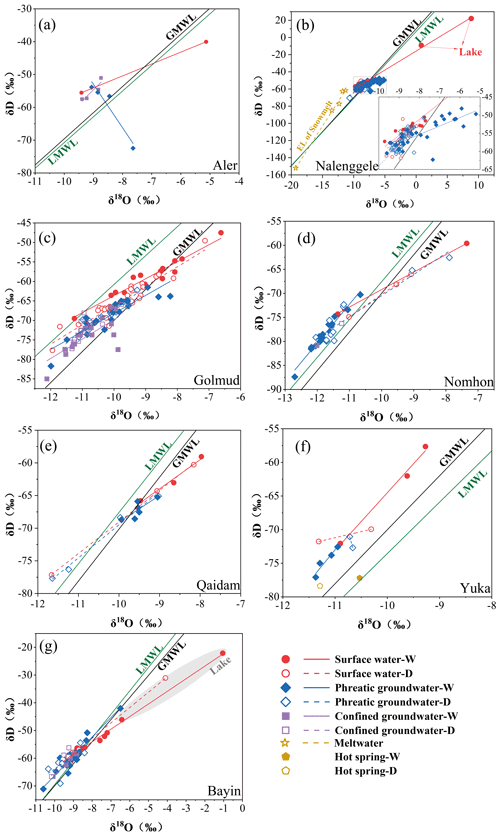

4.3 Isotopic variations in different water bodies

In the Qaidam Basin, the ranges of δ18O and δD of the precipitation samples from the Kunlun Mountains and Qilian Mountains are −23.38 ‰ to +2.55 ‰ and −158.6 ‰ to +30.5 ‰, respectively (Table S1 in the Supplement; Zhu et al., 2015). The fitted local meteoric water line (LMWL) equation in the Qaidam Basin is δD = 7.48δ18O + 11.30 (R2=0.95, n=74), where the slope and intercept are similar to the long-term monitoring findings of the Qilian Mountains (Fig. 5; Zhao et al., 2011; Juan et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2023). In the Qaidam Basin, the heavy isotopes present in snow meltwater samples are considerably depleted compared to rainwater (Clark and Fritz, 1997). The δ18O and δD ranges are −19.30 ‰ to −2.19 ‰ and −152.0 ‰ to 32.4 ‰, respectively, and the fitting trend equation was δD = 9.21 δ18O + 31.78 (R2=0.89, n=12), with the slope and intercept being greater than the LMWL and GMWL (global meteoric water line).

The δ18O and δD ranges in river water are −13.51 ‰ to −5.93 ‰ and −85.0 ‰ to −47.5 ‰, respectively, whereas those in the lake water are more enriched at −4.10 ‰ to 8.84 ‰ and −31.1 ‰ to 22.1 ‰, respectively (Fig. 5). The fitted trend lines for river and lake samples are δD = 5.97 δ18O − 5.54 (R2=0.85, n=92) and δD = 4.64 δ18O − 16.37 (R2=0.99, n=7), respectively, which are below both the GMWL and LMWL, indicating varying extents of evaporative fractionation in the surface water bodies, with evaporation from lakes being more enhanced. The radioactive 3H concentrations range from 4.2 to 17.8 TU, with a mean value of 12.93 TU (n=23, Table S1).

The H–O isotopic composition ranges in the groundwater samples are wider, and considerable differences are observed between phreatic and confined groundwater (Fig. 5). The δ18O and δD values range in phreatic groundwater from −12.70 ‰ to −5.21 ‰ and −87.4 ‰ to −42.0 ‰, respectively. The fitted trend line is δD = 5.73 δ18O − 9.20 (R2=0.83, n=185). The phreatic groundwater isotopic composition and the slope of the trend line are similar to those of surface water, indicating considerable interactions between the two and substantial evaporative fractionation of some shallow groundwater. The δ18O and δD ranges in confined groundwater are relatively small and lower in comparison at −12.12 ‰ to −8.58 ‰ and −85.0 ‰ to −51.0 ‰. The linear regression relationship of the samples fitting (δD = 7.84 δ 18O + 12.39, R2=0.87, n=51) revealed that its slope and intercept were essentially consistent with those of the GMWL and LMWL, suggesting the presence of a strong correlation between confined groundwater and atmospheric precipitation in different periods. Radioactive 3H concentrations detectable in the phreatic and confined groundwater range from 0.22 to 30.35 TU and 0.60 to 12.76 TU, respectively, with mean values of 10.23 TU (n=49) and 7.55 TU (n=10), respectively (Table S1).

Overall, the stable H–O isotopic compositions of surface water and groundwater are generally more enriched in the Qaidam Basin. The isotopic compositions and trend-fitting features both demonstrated that the water samples have undergone varying degrees of evaporation during runoff, indicating the cold- and dry-climate environmental characteristics of the study area.

5.1 Water cycle information indicated by surface water isotopes

5.1.1 Atmospheric moisture transport pattern

To further explain the cause of spatial and seasonal variations of surface water δ18O and δD values, ERA5 reanalysis data in the rainy season (June to September) were used to calculate the water vapor flux field in the Qaidam Basin and its surrounding areas, as well as to track the main trajectories of the moisture transport (Hersbach et al., 2019). The results show that the mid-latitude westerlies dominate the moisture paths inside and around the basin, and the water vapor flux in the eastern basin is notably greater than that in the western basin (Fig. 6; Yang and Wang, 2020). This largely explains the spatial patterns of river water H–O isotopes (Fig. 3), as well as temperature and precipitation regimes (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). Atmospheric and isotopic tracing data also support these conclusions. For instance, the Tanggula Mountains (33–35∘ N) serve as the physical and chemical boundary of the Tibetan Plateau, and the westerlies fundamentally govern the northern region, preventing the Indian monsoon from having a significant impact on the Qaidam Basin (Yao et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Furthermore, d-excess can effectively represent the moisture source properties. The mean d-excess of basin river water during the wet season (11.45 ‰, Table S1) was greater than 10 ‰, associated with the characteristics of an alpine arid continental climate and a moisture source devoid of monsoon influences. Higher d-excess values are attributed to westerlies moisture and recycled moisture that is boosted by inland surface evaporation. In contrast, the hinterland of the Tibetan Plateau, south of the Tanggula Mountains, which was subject to significant influences from the Indian monsoon circulation, had summer precipitation and river water d-excess values that ranged from 5 ‰ to 9 ‰, with a mean value of 7 ‰ (Tian et al., 2001). The stark contrasts in the d-excess values between the two regions further support the above inference about the moisture sources of the Qaidam Basin.

5.1.2 Isotopic records of surface water to precipitation

Owing to the sparse precipitation in the alpine arid region and its concentration in summer (June to September), surface water isotopic records may mimic local precipitation characteristics during the wet season. On a seasonal basis, the positive correlations between isotopic variations in surface water (Fig. 3) and those in precipitation are extremely strong across most of the basin and its surrounding areas (Liu et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2011; Juan et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022). In particular, the δ18O values in the mountainous areas of each watershed are higher during the wet season compared to the dry season, reflecting the input of precipitation with heavy isotopic signatures to the river. Moreover, the mean δ18O and δD values are higher in watersheds (such as the Qaidam and Bayin rivers) during the wet season, with correspondingly excessive rainfall (Fig. S1). From this, the river water isotopes of each watershed in the basin that are primarily impacted by summer precipitation during the wet season could be inferred. This is mostly because, during the rainy season, relatively intensive rainfall events can create surface runoff and increase river flows.

5.1.3 Climate impact on isotopic spatial and temporal variation

The spatial variation of surface water isotopes of the eastern Kunlun Mountains water system (Fig. 3) reflects the variation of precipitation isotopes which are strongly influenced by westerlies moisture transport. Heavy isotopes are preferentially separated in raindrop condensation along the westerlies trajectory, and long-distance moisture advection leads to heavy-isotope-depleted precipitation due to rainout (Wang et al., 2016; Yang and Wang, 2020). Meanwhile, the isotope variations in the two watersheds in the Qilian Mountains are opposite to those in the eastern Kunlun Mountains. Comparing the meteorological parameters of Delingha and Da Qaidam (refer to Fig. S1 for specific location) from 2010 to 2020, the mean annual precipitation of Delingha (276.36 mm) was 2.41 times higher than that of Da Qaidam (114.79 mm), and the mean annual temperature of Delingha (5.23 ∘C) was 1.58 ∘C higher than that of Da Qaidam (3.65 ∘C). Precipitation in the Bayin River has increased by up to 25.09 mm per decade since 1961 (Fig. S1). The seasonal δ18O variation in the Bayin River is roughly 1.79 times that of the Yuka River due to the marked increase in precipitation in Delingha. Under similar conditions of ice and/or snow meltwater recharge, the mean δ18O and δD values of the Bayin River are higher than 1.52 ‰ and 7.3 ‰, respectively, relative to that of the Yuka River, which can be attributed to a greater proportional contribution of precipitation with heavy isotopic signatures. As a result, the change in river water isotopes in the Qilian Mountains can be attributed to the differences in temperature and precipitation regimes, as well as the extents of warming and humidification between the watersheds.

Given the spatial and temporal variations of surface water δ18O–δD (Fig. 3), samples from different water bodies within each watershed were incorporated into the δ18O–δD plot (Fig. 7). The considerable differences in the dual-isotopic spectrum imply that seasonal variations in surface water isotopes in each watershed may be attributed to variability in the contribution ratios of precipitation, ice and/or snow meltwater, and groundwater throughout both the wet and dry seasons. Hence, Eq. (1) of the MixSIAR model was employed to estimate the contribution of each potential recharge endmember to river water (Table 1). The findings reveal that groundwater discharge in mountainous areas maintains the base flow in each watershed during the dry season, with groundwater contribution being up to 97 % of the total flow. Various proportions of precipitation, ice and/or snow meltwater, and groundwater feed the river water during the wet season. For example, in the area with the greatest annual precipitation, the contribution of summer precipitation to the Bayin River during the wet season may reach 84 %. Thus, variabilities in the proportional contributions of each recharge endmember during wet and dry seasons are the main factors responsible for the seasonal variations in surface water isotopes in each watershed.

In summary, the spatial and seasonal variations of surface water stable isotopes are caused by the interaction of regional warming and humidification trends, the intensity of mid-latitude westerlies moisture transport, and local hydrometeorological conditions.

Figure 7δ18O–δD plots in different water bodies in each watershed of the Qaidam Basin during dry and wet seasons. W and D represent wet and dry seasons, respectively. Data source of LMWLs: (a, b) Xu et al., 2017; (c) this study; (d, e) Xiao et al., 2017; (f) Zhu et al., 2015; (g) Tian et al., 2001.

5.2 Multi-sources of groundwater recharge and circulation mechanism

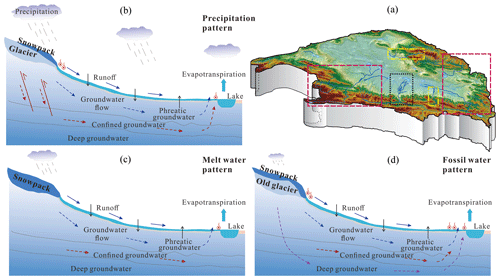

Seasonal variations in groundwater aquifer H–O isotopes in each watershed suggest that their recharge sources, forms and rates fluctuate. The δ18O–δD correlations of different seasons and types of water samples can be used to deduce the groundwater source compositions and recharge patterns. According to the seasonal variations in groundwater δ18O–δD in each watershed (Fig. 4) and the dual-isotopic spectrum of different water bodies within the watershed (Fig. 7), the Qaidam Basin groundwater systems can be divided into three recharge types: modern precipitation- and glacier snowmelt-water-dominated recharge and fossil water.

Figure 9Schematic diagram of the Qaidam Basin water cycle model ((b) represents the dashed purple box, (c) represents the dashed yellow box, and (d) represents the dashed black box).

5.2.1 Precipitation-dominated recharge

In the Nalenggele River, which is situated in the southwestern basin, and the Qaidam and Bayin rivers in the eastern basin, groundwater δ18O and δD values are markedly positive in the wet season and negative in the dry season (Fig. 4). The groundwater isotope data in the majority of the wet season cluster near the LMWL and GMWL compared to those during the dry season (Fig. 7b, e, g), indicating that the isotopic signatures are similar to the river water and summer precipitation in the same period (Table S1; Zhu et al., 2015), with different trends in evaporation. These results suggest that precipitation recharges groundwater during the wet season. The significant seasonal variations of H–O isotopes show that the aquifers in the eastern and southwestern Qaidam Basin have relatively rapid groundwater circulation and seasonal recharge. There is an abundance and notable rise in precipitation in the eastern basin (Fig. S1). An interesting finding was that increased precipitation has directly caused a rise of 5 m in water level and an area expansion of 1.59 times in a lake near the headwaters of the Nalenggele River in the southwestern basin from 1995 to 2015 (Chen et al., 2019). The abundant precipitation observed in the eastern-basin headwater may also be a potential source for the rapid seasonal groundwater recharge associated with rapid warming and humidification. Furthermore, the tectonic conditions of the recharge area are believed to enhance seasonal groundwater recharge. The three watersheds coincide with collision zones of intensive neotectonic movement, where a considerable number of deep faults and other volcanic channels have developed within recharge areas (Fig. 2; Tan et al., 2021). It can be concluded that favorable hydrological and tectonic conditions facilitate the formation of direct rapid groundwater recharge of precipitation and meltwater through bedrock fissures at high altitudes under large hydraulic heads (>1000 m), resulting in significant seasonal variations in the groundwater H–O isotopes in these regions.

5.2.2 Glacier snowmelt-water-dominated recharge

In the Nomhon and Yuka rivers, located in the middle region of the basin, groundwater H–O isotopes are more depleted in the wet season than in the dry season (Table S1; Fig. 4). Most of the δ18O–δD data for the groundwater samples in these two watersheds are observed in the lower left of the LMWL and GMWL (Fig. 7d and f), and these values are more negative relative to river water, with characteristics parallel to those measured in snowmelt water obtained from the high-altitude eastern Kunlun Mountain (Fig. 5; Yang et al., 2016). This shows that the groundwater recharged by ice and/or snow meltwater is more isotopically depleted during both the wet and dry seasons despite the fact that precipitation contributes less to the aquifer. Similarly, non-monsoonal meltwater control of hydrological processes in monsoonal groundwater systems has also been observed on the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau (Kong et al., 2019). The isotope signals suggested that isotopically depleted ice and/or snow meltwater in the source region was released due to elevated summer temperatures and further depleted the groundwater after mixing with groundwater recharged by seasonal meltwater. Furthermore, due to the scarce precipitation in these two watersheds (61.39 and 121.78 mm, respectively, Fig. S1) and the fact that even fewer precipitation events occurred in 2020, the seasonal direct recharge to the aquifer from the limited precipitation was negligible in this extremely arid climate.

5.2.3 Fossil-water-dominated recharge

In the Golmud River, the mean δ18O value is 0.33 ‰ higher during the wet season than during the dry season, with insignificant seasonal changes, indicating a limited share of seasonal groundwater recharge and a slow renewal rate. The groundwater H–O isotope data lay mainly between the LMWL and GMWL (Fig. 7c), implying that the predominant recharge source is the combination of different periods of atmospheric precipitation (Beyerle et al., 1998). Furthermore, the groundwater δ18O and δD values exhibit a gradually decreasing trend along the flow path (Fig. 8a, b). For this watershed, a prominent feature is the sizable storage of confined groundwater, which is constantly discharging at the front edge of the alluvial fan. Confined groundwater δ18O and δD values are more negative than those of phreatic groundwater, and the mean δ18O values are similar during the wet and dry seasons, with minor seasonal variations (Table S1). We hypothesize that phreatic groundwater is recharged primarily by ice and/or snow meltwater, while confined groundwater is slowly and stably recharged and may be sustained by precipitation with low δ18O and δD values or fossil water formed during relatively cold climate periods (Xiao et al., 2018). This scenario is, in fact, observed in deep confined groundwater in many areas in the world (Ma et al., 2009; Jasechko et al., 2017).

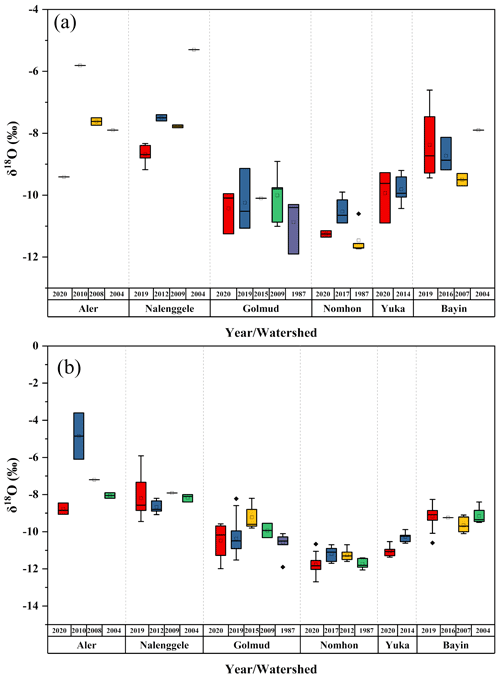

Figure 11Interannual variations in the river water (a) and groundwater (b) δ18O in the Qaidam Basin. Date source: Aler: 2004 – Wang et al., 2008, 2008 – Tan et al., 2009, 2010 – Ye et al., 2015. Nalenggele: 2004 – Wang et al., 2008, 2009 – Tan et al., 2012, 2012 – Xu et al., 2017. Golmud: 1987 – Wang et al., 2008, 2009 – Tan et al., 2012, 2015 – Xiao et al., 2018. Nomhon: 1987 – Wang et al., 2008, 2012 – Cui et al., 2015, 2017 – Zhao et al., 2018. Yuka: 2014 – Zhu, 2015. Bayin: 2004 – Wang et al., 2008, 2007 – He et al., 2016, 2016 – Wen et al., 2018.

5.2.4 Mechanism governing the water cycle in alpine mountain basin systems

Radioactive 3H, tritium, with a half-life of 12.32 years, can be used to estimate the migration time of younger water. Particularly in mixed water bodies consisting of younger water and fossil water, 3H can be used to effectively characterize groundwater age and renewal rate (Stewart et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2018; Chatterjee et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2021). In accordance with the significant differences in δ18O–δD of the various water bodies in each watershed (Figs. 7, 8a, b), the scale of the groundwater recharge in the Qaidam Basin is further constrained with 3H (Fig. 8c, d). The spatial pattern of 3H reveals that groundwater recharge rates varied significantly at both intra- and inter-watershed scales (Fig. 8c, d). Thus, the groundwater system is dominated by both regional and local recharge.

At the watershed scale, the 3H concentration of phreatic groundwater is significantly higher in alluvial fan areas along the river channel and mountain pass (Table S1; Fig. 8c, d) and approximates that of the river water. This suggests that there is a close hydraulic connection between surface water and groundwater and that the aquifer also receives river water through vertical infiltration and lateral recharge. This portion of groundwater is therefore mostly seasonal and younger and has a rather rapid renewal rate. 3H concentrations in the periphery of phreatic and confined groundwater are typically less than 3 TU, indicating that 3H is dead in comparison to that near the river channel. These findings suggest that these aquifers are mostly recharged by lateral flow, consisting primarily of sub-modern water (>60 years) or fossil water, with limited mixing of modern precipitation and seasonal meltwater and a slow renewal rate. This is especially evident in the Golmud and Nomhon rivers (Liu et al., 2014; Cui et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2017, 2018), highlighting the importance of fossil water content in recharging the aquifer in extremely arid regions.

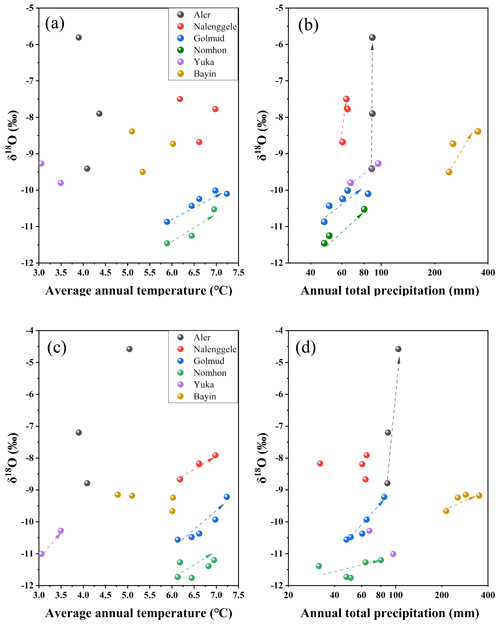

Figure 12Surface water δ18O and temperature (a) and precipitation (b); groundwater δ18O and temperature (c) and precipitation (d) in the Qaidam Basin. The light lines indicate δ18O change with temperature and precipitation.

At the basin scale, 3H data are consistent with seasonal variations in stable H–O isotopes. Seasonal variations in δ18O and δD values correspond to higher average 3H concentrations in phreatic groundwater systems in the eastern and southwestern basins, revealing that seasonal groundwater recharge is more significant and that groundwater age is, overall, younger (<60 years). Based on river seepage, modern meltwater and precipitation may potentially infiltrate through preferential flow paths, such as fault zones developed on a large scale in the recharge area, resulting in rapid aquifer recharge (Fig. 9b; Tan et al., 2021). The contrary was observed in the phreatic groundwater systems of the western Qilian Mountains and the middle eastern Kunlun Mountains, where the depletion in heavy isotopes during the wet season, accompanied by low 3H concentrations, meant these aquifers were primarily recharged by seasonal ice and/or snow meltwater. In contrast, the groundwater renewal rate was relatively slow owing to smaller and steadier meltwater recharge (Fig. 9c).

In confined groundwater, heavy H–O isotope depletion is greatest, with most samples having very low 3H concentrations (<3 TU), indicating a very slow recharge rate. Furthermore, most of the confined groundwater was over 100 years old and consisted mainly of sub-modern groundwater or fossil water (Xiao et al., 2018). In the Golmud River, the confined groundwater in the discharge zone continued to discharge after nearly half a century of extraction, and the pressure heads did not decrease, implying that modern precipitation or ice and/or snow meltwater may recharge deep confined groundwater. Some confined groundwaters possess discernible seasonal isotopic effects, and the existence of a certain proportion of ongoing recharge, even on a seasonal scale, cannot be excluded. Large karst springs have also developed in the mountainous areas of Golmud River. Well-formed karst caves and fissures provide conduits for direct precipitation or meltwater infiltration. With deep circulation, precipitation and meltwater generate regional subsurface flow that recharges the confined groundwater in the overflow zone in the long term, allowing continuous flow under a large hydraulic head (about 1000 m) (Fig. 9d). Moreover, the H–O isotopic signals of confined groundwater in part of the alluvial fan front in the Golmud and Bayin rivers are largely similar to those of the nearby phreatic groundwater, with 3H concentrations close to 10 TU. These findings also suggest that confined groundwater recharge may have occurred through aquitards or by leakage recharge in nearby skylights.

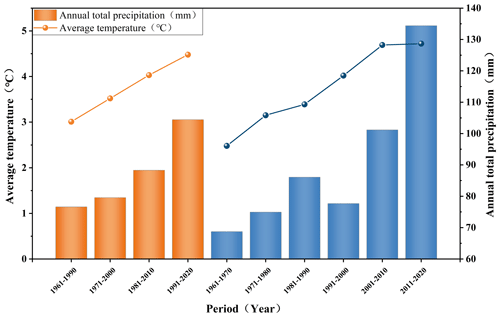

5.3 Isotope hydrology responses to climate change and indications of water cycle trends

The Qaidam Basin has experienced rapid warming at a rate more than twice the global average since the 1980s (Wang et al., 2014; Kuang and Jiao, 2016; Yao et al., 2022). Since 1961, the 10- and 30-year mean temperature and precipitation changes and rising rates at eight meteorological stations in the basin have demonstrated that the current warming and humidification trends in this basin of the northeastern Tibetan Plateau are continuously strengthening (Fig. 10). Changes in surface water and groundwater isotopes in the Qaidam Basin reflect different sensitivities to climate change at both seasonal and multi-year scales. Previously, it was assumed that the isotopic composition of the surface water and groundwater systems did not vary with time, at least at interannual intervals, and was rather stable (Boutt et al., 2019). However, isotopic measurements in water bodies over the past 40 years suggest that there is a range of interannual variability in surface water and groundwater isotopes, with interannual variability in mean δ18O values greater than 3 ‰ (Fig. 11). The spatial and temporal variability of isotopic signals can be ascribed to differences in the extent of warming and humidification across the basins. Wang et al. (2014) highlighted that, while the Qaidam Basin has experienced rapid warming over the past 50 years, warming and humidification have been markedly asynchronous in different regions, with rates of temperature increase ranging from 0.31 to 0.89∘ per decade and the rates of rainfall increase ranging from 1.77 to 25.09 mm per decade (Fig. S1). It is noteworthy that surface water is more responsive to precipitation, whereas groundwater is more sensitive to temperature (Fig. 12). This phenomenon suggests that increased precipitation may influence the water cycle by promoting slope runoff and groundwater infiltration in mountainous areas, and the warming will cause the solid water ablation at higher elevations, thereby accelerating groundwater recharge to aquifers through bedrock fissures. In addition, elegant remote sensing monitoring findings suggested that the increase in terrestrial water storage in the Qaidam Basin was strongly correlated with increased precipitation and glacier meltwater recharge (Song et al., 2014; Jiao et al., 2015; Xiang et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2021; Zou et al., 2022), which fully supported the isotope-based conjecture. Furthermore, a recent study found that the accelerated conversion of ice and snow into liquid water on the Tibetan Plateau has led to an imbalance in the Asian Water Tower, with the Qaidam Basin being one of the key regions where liquid water has grown (Yao et al., 2022). The isotope, remote sensing and hydrometeorology data are consistent with the observation that the Qaidam Basin is the most rapidly and substantially warming region in the Tibetan Plateau. Global warming affects the basin by redistributing precipitation and melting ice and snow in high elevations, resulting in groundwater storage increases and lake expansions. The trend of increasing water storage in the Qaidam Basin is likely to continue in the 21st century. The highly coupled results of different observation methods further emphasize the sensitivity and potential of water isotopes in tracing water cycles and climate change.

Under the influence of climate change and the intensive cryosphere retreat, runoff has changed dramatically on the Tibetan Plateau, with significant effects on the spatial and temporal water resource distribution (Wang et al., 2021). The rapid changes in water resources in the Qaidam Basin are likely because of the following:

-

The surface water and groundwater resources will increase significantly in the short term (in recent decades) due to continued rapid warming and wetting. For example, water storage in the Bayin and Qaidam rivers in the eastern basin is likely to continue to increase with a high renewal capacity in the long term under the influence of sustained climate change and the abundant and significantly increasing precipitation. This phenomenon has been verified in many regions of the Tibetan Plateau, as well as in some alpine watersheds in high-latitude Switzerland (Xiang et al., 2016; Malard et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2021).

-

The decadal-scale climatic oscillation suggests that the massively shrinking cryosphere may not sustain surface water and groundwater recharge in the basin (Wang et al., 2023). It is expected that water resources in the southwestern basin (e.g., Nalenggele River) may continue to increase for a certain period followed by a large-scale decrease under future climate change scenarios. This is a general trend that has occurred in the Tibetan Plateau and in other regions around the world with large-scale glacial coverage area in alpine watersheds. Glaciers in the southwestern basin are reported to be losing mass regularly (−0.2 to −0.5 m a−1), a trend that has increased substantially from 2018 to 2020, notably at the headwaters of Nalenggele River, where glacier elevation has been reduced by 5.42 m since 2000 (Shen et al., 2022). However, completing the hydrologic budget will remain a challenge given strong decoupling between the rapid melting of ice and snow caused by warming versus scarce precipitation in the southwestern basin, even if precipitation continuously increases in the future.

-

In the middle basin (Nomhon, Golmud and Yuka rivers), there has been long-term, large-scale groundwater mining during agricultural and industrial development, accompanied by strong local evaporation. The sparse precipitation in the source area led to a melt dependence, although the surface water and groundwater recharge here are relatively stable.

-

Future groundwater level dropping seems to be inevitable in the basin, with glacier retreat and a reduction of meltwater in the mountainous source area. Monitoring data from five shallow groundwater boreholes along the alluvial fan belt of the Golmud River show that groundwater levels have fluctuated since 2011, declining by an average of −1.18 m a−1 (Fig. S2). Therefore, whether the enhanced water resource renewal capacity and water storage in the Qaidam Basin can stay stable in the future is a scientific issue worth considering.

The spatial and temporal variations of δ18O and δD in the surface water and groundwater of the Qaidam Basin reflect their dynamic hydrological responses to climate change, water sources, and local temperature and precipitation regimes, especially precipitation, at interannual and seasonal scales.

-

The mean values of surface water δ18O and δD in the eastern Kunlun Mountains gradually decrease eastward, whereas the opposite is true for the Qilian Mountains river system, reflecting the intensity of westerlies moisture transport and the influence of local climatic conditions, respectively. Surface water is enriched in heavy H–O isotopes during the wet season and is relatively depleted during the dry season. River base flow is maintained by groundwater discharge during the dry season, and rivers receive varying proportions of groundwater (26 %–62 %), ice and/or snow meltwater (23 %–47 %), and precipitation (10 %–45 %) during the wet season. The seasonal isotopic variability is determined by the quantity of precipitation and its gradient in the basin, with precipitation in the Qilian Mountains contributing more to rivers than in the eastern Kunlun Mountains.

-

The key factor accelerating groundwater circulation in the Qaidam Basin is the contribution of precipitation and meltwater produced by climate change. The groundwater systems located in the collision and convergence zone of several mountain ranges are distinguished by enriched H–O isotopes during the wet season, high 3H concentrations and marked rapid seasonal recharge. Modern precipitation and meltwater can infiltrate through favorable structural conduits (e.g., large-scale active fault zones), resulting in rapid groundwater recharge. In contrast, the groundwater systems in the western Qilian Mountains and the middle eastern Kunlun Mountains are depleted in H–O isotopes during the wet season, and 3H concentrations are low and are primarily slowly recharged by seasonal ice and/or snow meltwater, which consisted of modern water and sub-modern water (>60 years). The confined groundwater is considerably depleted in H–O isotopes and, for the most part, exhibits imperceptible seasonal changes. 3H concentrations are very low, and recharge is quite slow, dominated by fossil water.

-

Warming climate has exerted a substantial impact on the hydrological processes across the basin, accelerating the water cycle and increasing water storage in the eastern and southwestern basins through the increased precipitation and melting of glaciers and snow. However, this increasing trend of water resources in the basin seems to be unsustainable. The southwestern basin could suffer a rapid loss in total water resources in the future as precipitation increases and solid-water ablation in mountainous areas becomes severely out of balance due to climatic extreme changes.

The complete list of isotopes and their values is available in Table S1 in the Supplement. The meteorological data can be obtained on the China Meteorological Data Network (http://data.cma.cn, last access: 9 January 2022). The monthly mean ERA5 reanalysis data () can be obtained from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF, https://www.ecmwf.int/, last access: 1 June 2022).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-27-4019-2023-supplement.

Conceptualization: YZ, HT. Funding acquisition: XZ. Investigation: PC. Resources: WR. Visualization: DS. Writing – original draft: YZ. Writing – review and editing: HT.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We thank the editors, Michael K. Stewart and the two anonymous reviewers for providing a list of critical and very valuable comments that helped to improve the paper. We also thank Roger D. Beckie for the writing suggestions and thoughtful reviews with the final revision. We would like to express our gratitude for all the members' help in both the field observation and geochemical analysis in the laboratory.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. U22A20573), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (STEP) (grant no. 2022QZKK0202), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. B230205010), and the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (grant no. KYCX22_0666).

This paper was edited by Markus Hrachowitz and reviewed by Michael Stewart and two anonymous referees.

Ahmed, M., Chen, Y., and Khalil, M. M.: Isotopic Composition of Groundwater Resources in Arid Environments, J. Hydrol., 609, 127773, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127773, 2022.

Bam, E. K., Ireson, A. M., van Der Kamp, G., and Hendry, J. M.: Ephemeral ponds: Are they the dominant source of depression-focused groundwater recharge?, Water. Resour. Res., 56, e2019WR026640, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR026640, 2020.

Befus, K. M., Jasechko, S., Luijendijk, E., Gleeson, T., and Bayani Cardenas, M.: The rapid yet uneven turnover of Earth's groundwater, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 5511–5520, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073322, 2017.

Benettin, P., Rodriguez, N. B., Sprenger, M., Kim, M., Klaus, J., Harman, C. J., Van Der Velde, Y., Hrachowitz, M., Botter, G., McGuire, K. J., Kirchner, J. W., Rinaldo, A., and McDonnell, J. J.: Transit time estimation in catchments: Recent developments and future directions, Water. Resour. Res., 58, e2022WR033096, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022WR033096, 2022.

Beyerle, U., Purtschert, R., Aeschbach-Hertig, W., Imboden, D. M., Loosli, H. H., Wieler, R., and Kipfer, R.: Climate and groundwater recharge during the last glaciation in an ice-covered region, Science, 282, 731–734, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.282.5389.731, 1998.

Boutt, D. F., Mabee S. B., and Yu, Q.: Multiyear increase in the stable isotopic composition of stream water from groundwater recharge due to extreme precipitation, Geophys. Res. Lett., 46, 5323–5330, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL082828, 2019.

Bowen, G. J., Cai, Z., Fiorella, R. P., and Putman, A. L.: Isotopes in the water cycle: regional-to global-scale patterns and applications, Annu. Rev. Earth. Pl. Sci., 47, 453–479, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-053018-060220, 2019.

Chang, Q., Ma, R., Sun, Z., Zhou, A., Hu, Y., and Liu, Y.: Using isotopic and geochemical tracers to determine the contribution of glacier-snow meltwater to streamflow in a partly glacierized alpine-gorge catchment in northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 123, 10–037, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD028683, 2018.

Chatterjee, S., Gusyev, M. A., Sinha, U. K., Mohokar, H. V., and Dash, A.: Understanding water circulation with tritium tracer in the Tural-Rajwadi geothermal area, India, Appl. Geochem., 109, 104373, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2019.104373, 2019.

Chen, J., Wang Y., Zheng, J., and Cao, L.: The changes in the water volume of Ayakekumu Lake based on satellite remote sensing data, J. Nat. Res., 34, 1331–1344, https://doi.org/10.31497/zrzyxb.20190618, 2019 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Clark, I. D. and Fritz, P.: Environmental isotopes in hydrogeology, CRC press, Boca Raton, 342 pp., ISBN 9780429069574, 1997.

Condon, L. E., Atchley, A. L., and Maxwell, R. M.: Evapotransspiration depletes groundwater under warming over the contiguous United States, Nat. Commun., 11, 1-8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14688-0, 2020.

Craig, H.: Isotopic variations in meteoric waters, Science, 133, 1702–1703, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.133.3465.170, 1961.

Cui, Y., Liu, F., and Hao, Q.: Characteristics of hydrogen and oxygen isotopes and renewability of groundwater in the Nuomuhong alluvial fan, Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol., 42, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.16030/j.cnki.issn.1000-3665.2015.06.01, 2015 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Dansgaard, W.: Stable isotopes in precipitation, Tellus, 16, 436–468, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusa.v16i4.8993, 1964.

Durack, P. J., Wijffels, S. E., and Matear, R. J.: Ocean salinities reveal strong global water cycle intensification during 1950 to 2000, Science, 336, 455–458, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1212222, 2012.

Haddeland, I., Heinke, J., Biemans, H., Eisner, S., Flörke, M., Hanasaki, N., Konzmann, M., Ludwig, F., Masaki, Y., Schewe, J., Stacke, T., Tessler, Z. D., Wada, Y., and Wisser, D.: Global water resources affected by human interventions and climate change, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, 3251–3256, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.122247511, 2014.

He, Y., Zhao, C., Liu, Z., Wang, H., Liu, W., Yu, Z., Zhao, Y., and Ito, E.: Holocene climate controls on water isotopic variations on the northeastern Tibetan Plateau, Chem. Geol., 440, 239–247, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.07.024, 2016.

Hersbach, H., Bell, W., Berrisford, P., Horányi, A. J. M.-S., Nicolas, J., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., and Dee, D.: Global reanalysis: goodbye ERA-Interim, hello ERA5, ECMWF Newslett., 159, 17–24, https://doi.org/10.21957/vf291hehd7, 2019.

Hooper, R. P.: Diagnostic tools for mixing models of stream water chemistry, Water. Resour. Res., 3, 1055, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002WR001528, 2003.

Hooper, R. P., Christophersen, N., and Peters, N. E.: Modeling streamwater chemistry as a mixture of soilwater end-members – An application to the Panola Mountain catchment, Georgia, USA, J. Hydrol., 116, 321–343, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(90)90131-G, 1990.

Huntington, T. G.: Evidence for intensification of the global water cycle: review and synthesis, J. Hydrol., 319, 83–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.07.003, 2006.

Jasechko, S., Birks, S. J., Gleeson, T., Wada, Y., Fawcett, P. J., Sharp, Z. D., McDonnell, J. J., and Welker, J. M.: The pronounced seasonality of global groundwater recharge, Water. Resour. Res., 50, 8845–8867, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014WR015809, 2014.

Jasechko, S., Perrone, D., Befus, K. M., Bayani Cardenas, M., Ferguson, G., Gleeson, T., Luijendijk, E., McDonnell, J. J., Taylor, R. G., Wada, Y., and Kirchner, J. W.: Global aquifers dominated by fossil groundwaters but wells vulnerable to modern contamination, Nat. Geosci., 10, 425–429, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2943, 2017.

Jiao, J. J., Zhang, X., Liu, Y., and Kuang, X.: Increased water storage in the Qaidam Basin, the North Tibet Plateau from GRACE gravity data, Plos One, 10, e0141442, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141442, 2015.

Juan, G., Li, Z., Qi, F., Ruifeng, Y., Tingting, N., Baijuan, Z., Jian, X., Wende, G., Fusen, N,. Weixuan, N., Anle, Y., and Pengfei, L.: Environmental effect and spatiotemporal pattern of stable isotopes in precipitation on the transition zone between the Tibetan Plateau and arid region, Sci. Total. Environ., 749, 141559, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141559, 2020.

Kang, S., Cong, Z., Wang, X., Zhang, Q., Ji, Z., Zhang, Y., and Xu, B.: The transboundary transport of air pollutants and their environmental impacts on Tibetan Plateau, Chinese. Sci. Bull., 64, 2876–2884, https://doi.org/10.1360/TB-2019-0135, 2019.

Ke, L., Song, C., Wang, J., Sheng, Y., Ding, X., Yong, B., Ma, R., Liu, K., Zhan, P., and Luo, S.: Constraining the contribution of glacier mass balance to the Tibetan lake growth in the early 21st century, Remote. Sens. Environ., 268, 112779, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112779, 2022.

Kong, Y., Wang, K., Pu, T., and Shi, X.: Nonmonsoon precipitation dominates groundwater recharge beneath a monsoon-affected glacier in Tibetan Plateau, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 124, 10913–10930, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD030492, 2019.

Kuang, X., and Jiao, J. J.: Review on climate change on the Tibetan Plateau during the last half century, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 121, 3979–4007, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD024728, 2016.

Li, L. and Garzione, C. N.: Spatial distribution and controlling factors of stable isotopes in meteoric waters on the Tibetan Plateau: Implications for paleoelevation reconstruction, Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett., 460, 302–314, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2016.11.046, 2017.

Li, L., Shen, H., Li, H., and Xiao, J.: Regional differences of climate change in Qaidam Basin and its contributing factors, J. Nat. Res., 30, 641–650, 2015 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liu, F., Cui, Y., Zhang, G., Geng, F., and Liu, J.: Using the 3H and 14C dating methods to calculate the groundwater age in Nuomuhong, Qaidam Basin, Geoscience, 28, 1322–1328, 2014 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liu, J., Song, X., Sun, X., Yuan, G., Liu, X., and Wang, S.: Isotopic composition of precipitation over Arid Northwestern China and its implications for the water vapor origin, J. Geo. Sci., 19, 164–174, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-009-0164-3, 2009.

Ma, J., Ding, Z., Edmunds, W. M., Gates, J. B., and Huang, T.: Limits to recharge of groundwater from Tibetan plateau to the Gobi desert, implications for water management in the mountain front, J. Hydrol., 364, 128–141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.10.010, 2009.

Malard, A., Sinreich, M., and Jeannin, P. Y.: A novel approach for estimating karst groundwater recharge in mountainous regions and its application in Switzerland, Hydrol. Process., 30, 2153–2166, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.10765, 2016.

Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Huang, M., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B.: Climate change 2021: the physical science basis, Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896, 2021.

Moran, B. J, Boutt, D. F, and Munk, L. A.: Stable and radioisotope systematics reveal fossil water as fundamental characteristic of arid orogenic-scale groundwater systems, Water. Resour. Res., 55, 11295–11315, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR026386, 2019.

Parnell, A. C., Inger, R., Bearhop, S., and Jackson, A. L.: Source partitioning using stable isotopes: coping with too much variation, Plos One, 5, e9672, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009672, 2010.

Rodriguez, N. B., Pfister, L., Zehe, E., and Klaus, J.: A comparison of catchment travel times and storage deduced from deuterium and tritium tracers using StorAge Selection functions, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 25, 401–428, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-401-2021, 2021.

Shen, C., Jia, L., and Ren, S.: Inter-and Intra-Annual Glacier Elevation Change in High Mountain Asia Region Based on ICESat-1&2 Data Using Elevation-Aspect Bin Analysis Method, Remote. Sens.-Basel, 14, 1630, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14071630, 2022.

Shi, D., Tan, H., Chen, X., Rao, W., and Basang, R.: Uncovering the mechanisms of seasonal river–groundwater circulation using isotopes and water chemistry in the middle reaches of the Yarlungzangbo River, Tibet, J. Hydrol., 603, 127010, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.127010, 2021.

Song, C., Huang, B., Richards, K., Ke, L., and Hien Phan, V.: Accelerated lake expansion on the Tibetan Plateau in the 2000s: Induced by glacial melting or other processes?, Water. Resour. Res., 50, 3170–3186, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR014724, 2014.

Stewart, M. K., Morgenstern, U., Gusyev, M. A., and Małoszewski, P.: Aggregation effects on tritium-based mean transit times and young water fractions in spatially heterogeneous catchments and groundwater systems, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 4615–4627, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-4615-2017, 2017.

Tan, H., Rao, W., Chen, J., Su, Z., Sun, X., and Liu, X.: Chemical and isotopic approach to groundwater cycle in western Qaidam Basin, China, Chin. Geogr. Sci., 19, 357–364, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-009-0357-9, 2009.

Tan, H., Chen, J., Rao, W., Zhang, W., and Zhou, H.: Geothermal constraints on enrichment of boron and lithium in salt lakes: An example from a river-salt lake system on the northern slope of the eastern Kunlun Mountains, China, J. Asian. Earth Sci., 51, 21–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.03.002, 2012.

Tan, H., Zhang, Y., Rao, W., Guo, H., Ta, W., Lu, S., and Cong, P.: Rapid groundwater circulation inferred from temporal water dynamics and isotopes in an arid system, Hydrol. Process., 35, e14225, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14225, 2021.

Tian, L., Yao, T., Sun, W., Stievenard, M., and Jouzel, J.: Relationship between δD and δ18O in precipitation on north and south of the Tibetan Plateau and moisture recycling, Sci. China. Ser. D, 44, 789–796, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02907091, 2001.

Wang, L., Yao, T., Chai, C., Cuo, L., Su, F., Zhang, F., Yao, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, X., Qi, J., Hu, Z., Liu, J., and Wang, Y.: TP-River: Monitoring and Quantifying Total River Runoff from the Third Pole, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 102, 948–965, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-20-0207.1, 2021.

Wang, S., Zhang, M., Che, Y., Chen, F., and Qiang, F.: Contribution of recycled moisture to precipitation in oases of arid central Asia: A stable isotope approach, Water. Resour. Res., 52, 3246–3257, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015WR018135, 2016.

Wang, S., Lei, S., Zhang, M., Hughes, C., Crawford, J., Liu, Z., and Qu, D.: Spatial and seasonal isotope variability in precipitation across China: Monthly isoscapes based on regionalized fuzzy clustering, J. Climate., 35, 3411–3425, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0451.1, 2022.

Wang, T., Yang, D., Yang, Y., Zheng, G., Jin, H., Li, X., Yao, T., and Cheng, G.: Unsustainable water supply from thawing permafrost on the Tibetan Plateau in a changing climate, Sci. Bull., 68, 1105–1108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2023.04.037, 2023.

Wang, X., Yang, M., Liang, X., Pang, G., Wan, G., Chen, X., and Luo, X.: The dramatic climate warming in the Qaidam Basin, northeastern Tibet Plateau, during 1961–2010, Int. J. Climatol., 34, 1524–1537, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3781, 2014.

Wang, X., Chen, M., Gong, P., and Wang, C.: Perfluorinated alkyl substances in snow as an atmospheric tracer for tracking the interactions between westerly winds and the Indian Monsoon over western China, Environ. Int., 124, 294–301, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.12.057, 2019.

Wang, Y., Guo, H., Li, J., Huang, Y., Liu, Z., Liu, C., Guo, X., Zhou, J., Shang, X., Li, J., Zhuang, Y., and Cheng, H.: Investigation and assessment of groundwater resources and their environmental issues in the Qaidam Basin, Geological Publishing House, Beijing, 447 pp., ISBN 978-7-116-05909-2, 2008 (in Chinese).

Wei, L., Jiang, S., Ren, L., Tan, H., Ta, W., Liu, Y., Yang, X., Zhang, L., and Duan, Z.: Spatiotemporal changes of terrestrial water storage and possible causes in the closed Qaidam Basin, China using GRACE and GRACE Follow-On data, J. Hydrol., 598, 126274, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126274, 2021.

Wen, G., Wang, W., Duan, L., Gu, X., Li, Y., and Zhao, J.: Quantitatively evaluating exchanging relationship between river water and groundwater in Bayin River Basin of northwest China using hydrochemistry and stable isotope, Arid Land Geography, 41, 734–743, https://doi.org/10.13826/j.cnki.cn65-1103/x.2018.04.008, 2018 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Wu, H., Zhang, C., Li, X. Y., Fu, C., Wu, H., Wang, P., and Liu, J.: Hydrometeorological Processes and Moisture Sources in the Northeastern Tibetan Plateau: Insights from a 7-Yr Study on Precipitation Isotopes, J. Climate., 35, 6519–6531, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0501.1, 2022.

Xiang, L., Wang, H., Steffen, H., Wu, P., Jia, L., Jiang, L., and Shen, Q.: Groundwater storage changes in the Tibetan Plateau and adjacent areas revealed from GRACE satellite gravity data, Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett., 449, 228–239, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2016.06.002, 2016.

Xiao, Y., Shao, J., Cui, Y., Zhang, G., and Zhang, Q.: Groundwater circulation and hydrogeochemical evolution in Nomhon of Qaidam Basin, northwest China, J. Earth Syst. Sci., 126, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-017-0800-8, 2017.

Xiao, Y., Shao, J., Frape, S. K., Cui, Y., Dang, X., Wang, S., and Ji, Y.: Groundwater origin, flow regime and geochemical evolution in arid endorheic watersheds: a case study from the Qaidam Basin, northwestern China, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 4381–4400, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-4381-2018, 2018.

Xu, W., Su, X., Dai, Z., Yang, F., Zhu, P., and Huang, Y.: Multi-tracer investigation of river and groundwater interactions: a case study in Nalenggele River basin, northwest China, Hydrogeol. J., 25, 2015–2029, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-017-1606-0, 2017.

Yang, N. and Wang, G.: Moisture sources and climate evolution during the last 30 kyr in northeastern Tibetan Plateau: Insights from groundwater isotopes (2H, 18O, 3H and 14C) and water vapor trajectories modeling, Quat. Sci. Rev., 242, 106426, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106426, 2020.

Yang, N., Zhou, P., Wang, G., Zhang, B., Shi, Z., Liao, F., Li, B., Chen, X., Guo, L., Dang, X., and Gu, X.: Hydrochemical and isotopic interpretation of interactions between surfaces water and groundwater in Delingha, Northwest China, J. Hydrol., 598, 126243, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126243, 2021.

Yang, N., Wang, G., Liao, F., Dang, X., and Gu, X.: Insights into moisture sources and evolution from groundwater isotopes (2H, 18O, 3H and 14C) in Northeastern Qaidam Basin, Northeast Tibetan Plateau, China, Sci. Total. Environ., 864, 160981, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160981, 2023.

Yang, Y., Wu, Q., and Jin, H.: Evolutions of water stable isotopes and the contributions of cryosphere to the alpine river on the Tibetan Plateau, Environ. Earth. Sci., 75, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-4894-5, 2016.

Yao, T., Masson-Delmotte, V., Gao, J., Yu, W., Yang, X., Risi, C., Sturm, C., Werner, M., Zhao, H., He, Y., Ren, W., Tian, L., Shi, C., and Hou, S.: A review of climatic controls on δ18O in precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau: Observations and simulations, Rev. Geophys., 51, 525–548, https://doi.org/10.1002/rog.20023, 2013.

Yao, T., Bolch, T., Chen, D., Gao, J., Immerzeel, W., Piao, S., Su, F., Thompson, L., Wada, Y., Wang, L., Wang, T., Wu,G., Xu, B., Yang, W., Zhang, G., and Zhao, P.: The imbalance of the Asian water tower, Nat. Rev. Earth. Env., 3, 618–632, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00299-4, 2022.

Ye, C., Zheng, M., Wang, Z., Hao, W., Wang, J., Lin, X., and Han, J.: Hydrochemical characteristics and sources of brines in the Gasikule salt lake, Northwest Qaidam Basin, China, Geochem. J., 49, 481–494, https://doi.org/10.2343/geochemj.2.0372, 2015.

Zhang, G., Yao, T., Shum, C. K, Yi, S., Yang, K., Xie, H., Feng, W., Bolch, T., Wang, L., Behrangi, A., Zhang, H., Wang, W., Xiang, Y., and Yu, J.: Lake volume and groundwater storage variations in Tibetan Plateau's endorheic basin, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 5550–5560, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073773, 2017.

Zhang, Q., Zhu, B., Yang, J., Ma, P., Liu, X., Lu, G., Wang, Y., Yu, H., Liu, W., and Wang, D.: New characteristics about the climate humidity trend in Northwest China, Chin. Sci. Bull., 66, 3757–3771, https://doi.org/10.1360/TB-2020-1396, 2021.

Zhang, X., Chen, J., Chen, J., Ma, F., and Wang, T.: Lake Expansion under the Groundwater Contribution in Qaidam Basin, China, Remote. Sens.-Basel, 14, 1756, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14071756, 2022.

Zhao, D., Wang, G., Liao, F., Yang, N., Jiang, W., Guo, L., Liu, C., and Shi, Z.: Groundwater-surface water interactions derived by hydrochemical and isotopic (222Rn, deuterium, oxygen-18) tracers in the Nomhon area, Qaidam Basin, NW China, J. Hydrol., 565, 650–661, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.08.066, 2018.

Zhao, L., Yin, L., Xiao, H., Cheng, G., Zhou, M., Yang, Y., Li, C., and Zhou, J.: Isotopic evidence for the moisture origin and composition of surface runoff in the headwaters of the Heihe River basin, Chin. Sci. Bull., 56, 406–415, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-010-4278-x, 2011.

Zhu, P.: Groundwater circulation patterns of Yuqia-Maihai Basin in the middle and lower reaches of Yuqia River, PhD thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, 2015 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhu, G., Liu, Y., Wang, L., Sang, L., Zhao, K., Zhang, Z., Lin, X., and Qiu, D.: The isotopes of precipitation have climate change signal in arid Central Asia, Global. Planet. Change, 225, 104103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2023.104103, 2023.

Zhu, J., Chen, H., and Gong, G.: Hydrogen and oxygen isotopic compositions of precipitation and its water vapor sources in Eastern Qaidam Basin, Environ. Sci., 36, 2784–2790, https://doi.org/10.13227/j.hjkx.2015.08.008, 2015 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zou, Y., Kuang, X., Feng, Y., Jiao, J. J., Liu, J., Wang, C., Fan, L., Wang, Q., Chen, J., Ji, F., Yao, Y., and Zheng, C.: Solid water melt dominates the increase of total groundwater storage in the Tibetan Plateau, Geophys. Res. Lett., e2022GL100092, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL100092, 2022.